The Lehman Trilogy has come to Broadway with the components of tragedy stuffed into its battered immigrant’s suitcase: spectacle, grandeur, collapse, sorrow. In its three and a half hours, it contains multiple deaths, three screaming nightmares, the Civil War, moral rot, the Depression, countless misunderstandings between fathers and sons, and — very briefly — the 2008 collapse of the Lehman Brothers financial-services firm. Those are all heavy things, and difficult to carry. How can a show bear up under them for so long? It doesn’t quite. There’s a feeling at the end of this atmospheric show, gorgeous and intoxicating as it often is, of a mighty steel beam bending out of true — all its strength can’t travel so far unsupported.

When The Lehman Trilogy was last in New York, it was at the titanic Park Avenue Armory, one of the few venues that can make a Broadway house seem cramped by comparison. At the Nederlander, audiences don’t get the Armory’s gull’s-eye view, but it’s well worth the (relatively) tight quarters to get close to the Lehmans themselves — the piece’s three stars Simon Russell Beale, Adam Godley, and Adrian Lester. The trio aren’t just Lehmans, actually. They play everyone in the show’s 154-year span, from squalling babies (Godley has a great squall), flirtatious maidens, stern plantation owners, heartbroken doctors, railroad magnates, and wild-eyed greed-is-good commodities traders. Director Sam Mendes builds a gleaming production around them, as though he’s setting jewels. The rare chance to see just one of these men perform is worth the price of admission. All three together — heartbreaking Beale and wall-shaking Lester and the living lightning bolt Godley — is a chance that will not come again.

Before The Lehman Trilogy was a play, it was a poem. Stefano Massini’s novel Qualcosa sui Lehman is written in verse, playful and complex, an epic about the birth and transformation and decline of the Lehman Brothers firm. The structure of the book rests on the Jewish tradition of sitting shiva, returning to moments when the Lehmans mourn one another (letting their beards grow long, greeting visitors) and concluding with generations of ghostly Lehmans sitting shiva for the firm itself. A master of the ritualistic, Massini includes dialogue and even references to staging and choreography; it’s clear why theater folks like Mendes and the writer Ben Power were eager to adapt it.

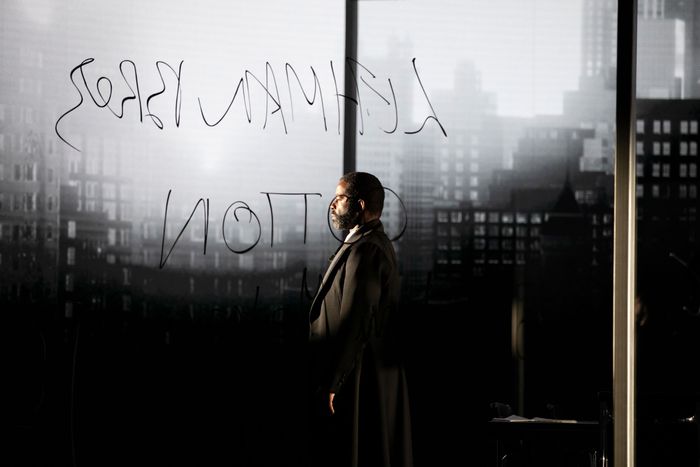

On stage, the Trilogy takes place in a Mies van de Rohe cube: a glass-walled office, complete with conference table and small reception area, a replica of what Halls of Power looked like in 2008. A janitor tidies up as he listens to a radio, which is breathlessly reporting the sudden collapse of Lehman Brothers. When he closes up, a man appears — Henry Lehman, played by Beale dressed in a long black coat and tidy white beard. It’s 1844, and Lehman is still Heyum Lehmann, having just stepped onto the dock after immigrating from Bavaria. He shakes a little.

Maybe it’s the emotion

or maybe, after a month and half at sea,

just standing still, on dry land:

Not rocking!

is strange.

But swiftly Lehman will shake the Old World from his name and European dirt from his shoes, and travel south to Alabama.

There his brothers Emmanuel (Lester) and Mayer (Godley) join him, and the three build a fabric business based on cheap cotton. After much hard work (and some unmentioned-by-the-play enslaved labor), their business changes: from acting as simple fabric merchants they become cotton brokers; then they emerge from the Civil War as bankers and financiers in New York, their wealth diversified across commodities. Beale also plays the silver-tongued Philip Lehman, Emmanuel’s son, who moves the company closer to the abstractions of the market, and Godley eventually plays Philip’s son, the luxury-loving Robert. Even as the three catapult along the script’s timeline, they never change their clothes. Costume designer Katrina Lindsay has dressed them in black, long, bell-skirted coats that somehow radiate both Gilded Age sumptuousness and Bavarian humility. They also accentuate the actors’ grace: The set sometimes rotates, and the three of them sway like dancers in a music box.

The set designer, Es Devlin, puts a huge cyclorama behind the glass office, a curving video-screen that shows us black-and-white images — a misty cotton field when the Lehmans are in Alabama, a changing New York skyline for the move north. Throughout the show, pianist Candida Caldicot plays Nick Powell’s show-long composition, and the music makes the time seem swift, the music like water tumbling over rocks. The show hasn’t just promised loveliness, though. The subject is Lehman, so we hope all the cascading language will contain some sophisticated thinking about the financial system, but the writers do not deliver. One does get the sense that the show laments the growth of complex financial instruments and would prefer that we went back to the time when people actually bought and sold tangible things, but it’s disturbing to link such thoughts to the plantation South. (The repeated implication that the Lehmans invented being “middlemen” would also be hilarious to whichever guy-in-a-tunic came up with it in ancient Sumer.)

Still, as a piece of stagecraft, the show is a symphony of theatermakers working at their pinnacle. The actors never stop being wonderful, and the set never stops being handsome, and the music never stops being beautiful. The music box spins on and on. But the play is strongest when talking about the original three Lehmans — the first part of the trilogy would be a standalone masterpiece — and the drama only grows less connected to its characters as it marches down the generations. In a way, the journey of The Lehman Trilogy replicates the mourning experience: The show starts with the sharp, astonishing grief of Beale’s opening speech, and then we spend a great deal of time together, changing that sorrow into something we can live with. It’s a process that necessarily puts the humanity of its figures farther from us as the hours wind forward. It’s not Henry any more, it’s just a business, we think somewhere in hour two. So Lehman’s ultimate collapse becomes a whisper, not a cry. We have already gone through a process of detachment; we have already let go.

The Lehman Trilogy is at the Nederlander Theatre.