On August 14, 1997, the Baltimore Orioles baseball game against the Seattle Mariners was postponed because some of the lights at Oriole Park at Camden Yards didn’t properly turn on. This much isn’t in dispute. But the reason for that light malfunction is at the center of a salacious, widespread urban legend that’s been passed around by sports fans for decades. Here’s the short version of it, all of which you should read with the word “ALLEGEDLY” blinking over it like a TV-studio applause sign: As the story goes, on the day in question, Orioles legend (and squeaky-clean baseball icon) Cal Ripken Jr. caught his wife in bed with actor Kevin Costner, got in a fight with Costner, and was so banged-up that he couldn’t play in that night’s game. So then, according to the story, the Orioles somehow caused a minor power outage in the stadium, so as to postpone the game until the next day and preserve Ripken’s record consecutive-games-played streak, which then stood at a remarkable 2,431 games.

The rumor — unlikely as it may seem — has always fascinated me, because I was actually in the ballpark that night. I was a couple weeks shy of teenagerdom and on vacation with my family, sitting in section 310, just underneath the faulty light tower in question. And so it was with great interest that I listened to The Rumor, a podcast hosted by Sam Dingman and Mac Montandon that investigated the Ripken-Costner rumor and released its sixth and final episode on Monday. Set into motion by a comment from an off-duty cop who had been told the rumor was actually true, Dingman and Montandon interviewed players, stadium employees, and other key figures in the postponement, while also obsessing over archival footage, scouring old documents, and even talking to pop-culture buffs like Vulture’s own Matt Zoller Seitz and Will Leitch to understand the Costner of it all.

To hear more about their exploration of the rumor, I spoke with lifelong Orioles fans Dingman and Montandon about Ripken, conspiracy theories, and why John Waters declining an interview probably wasn’t such a bad thing.

Sam, on the podcast, you talk about wanting to disprove the rumor, because you didn’t really want it to be true. How did you balance that in your head — on the one hand wanting to preserve the myth of your favorite ballplayer, while also wanting to make a podcast that would benefit from a splashy, newsy revelation?

Sam Dingman: With an ample amount of agita, to be sure. I knew that in looking into something like this, I was actually asking myself a deeper question, which is: Why do I still feel this attachment to this thing that I’m not sure serves me in the same way that it once did — and in fact often feels unhealthy: spending hours of my time watching a truly, horrifyingly terrible baseball team? But even more than that, I guess I’d reached a point in my life where it felt a little shallower or more facile to continue to associate any personal validity with something like baseball. And so as much as I did not want to dismantle this mythology about my childhood hero, I did have a sense for myself that if that is, in fact, what I learned, I knew that even if it was painful, it would be part of a maturation process.

Mac Montandon: I was a bit further removed from my intense fandom, so I think in terms of pursuing something that was uncomfortable and unpleasant, I was a little less conflicted. I’m obsessed with great stories, and from very early on, I could sense that this was going to be that. And as I said to Sam in our early conversations, if we found out all of this was true, to discover that Cal Ripken was a flawed human being would probably make me like him more. It would make this sort of cardboard figure of perfection into a flesh-and-blood, three-dimensional, complicated person, and who better to admire in the age of prestige cable shows than someone like that?

What made this particular urban legend so appealing that it’s still known more than two decades later?

Montandon: I think there’s probably a couple of different answers. The more simple one is that it involves very famous, very wealthy people, celebrities, sex, possible crimes, and one of the, if not the greatest record in sports. Anyone who loves a kind of juicy, salacious, gossipy story would be interested in this. But I think maybe the bigger, more complicated reason would be we’re in this moment of, like, peak conspiracy theory in some ways. And not to exactly align this story with other ones, like QAnon or Pizzagate, but I will say, I think the thing that does align our story with those, which is just sort of endlessly fascinating and has been since folklore tales were told around the fire, was this idea that there are unseen forces that are bigger than us that are sort of controlling even the narratives of our lives to some extent.

Like you said, Mac, we’re in this unfortunate peak period for conspiracy theories, including ones that are much more harmful than the one about Ripken and Costner. How did reporting on this change the way you look at the phenomenon of conspiracy theories?

Montandon: I think in some ways maybe we’re a little more sympathetic to a person who would be susceptible to, or drawn to, conspiracy theories. I had a couple of really great conversations with [Snopes co-founder] David Mikkelson, and he really helped contextualize a lot of that for us, how it comes out of a folklore tradition, and how in an overwhelming, chaotic world, which this current world most certainly is, it’s an extremely helpful way to try to make sense of things.

In the finale, my colleague Will Leitch talks about how crazy it is that this story spread so widely in an era before social media. He’d heard it in Illinois, I’d heard it in New York, you both knew it, my editor knew it. Were you able to pinpoint exactly how this story spread?

Montandon: I love thinking about that. The short answer is no, but the more interesting answer has to do with the attempts to find out. This happened so late in the project that I may not have mentioned it to Sam, but a friend of mine said he had once used this digital-forensics expert for something, so I asked him to ask this woman that he only knows as Mouse to look into this. Mouse was not able to determine where online it may have originated, and I trust that if she was not able to, that none of us would be able to. Sorry, Sam, I’m only telling you this now.

Dingman: It sounds like an episode seven, right?

I was actually at the postponed game in question, and I’d also happened to take a stadium tour earlier that afternoon. While listening to the podcast, I found myself studying the photos I took that day — of the light tower in the empty stadium, or of a light that appeared to have gone out inside the press box. But after a few minutes, I began to think to myself, like, What am I doing here? I’m basically looking at a photo of a light bulb. Did you have a similar moment of feeling silly obsessing over just the most innocuous thing?

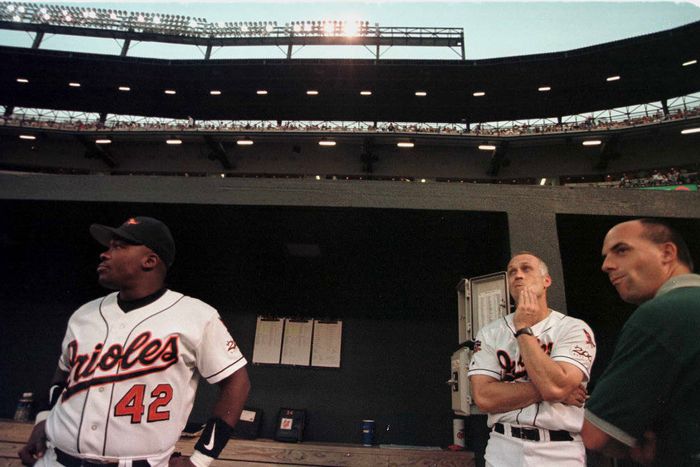

Dingman: There is a moment that we refer to as the “knuckle shadow” moment, where we’re staring at this B-roll footage from the local news that was at the stadium that night. It’s literally like five seconds of video where Cal is in the dugout and they’re looking up at the lights to try to figure out what’s going on. And from a narrative standpoint, it’s this fascinating moment, because on the one hand, it proves Cal’s alibi. Like, okay, he was there. No one can claim that he wasn’t present at the stadium and in uniform. But he’s leaning up against the wall of the dugout, and there’s this little shadow on his, I believe it’s his right hand, which ostensibly would have been his Costner-punching hand. And you see in this video that he’s looking around and then he looks right into the lens of the camera and, you know, you could interpret it that he looked into the lens of the camera, realizes that the camera is looking at him, and that his Costner-punching hand is in frame. And he moves it out of frame very, very quickly. And that was very much a moment where it was like, Oh, we have really gone ’round the bend here.

Montandon: This is sort of embarrassing to admit, but on the show we parse this police report where there’s a trespassing incident about a month before the power outage at the then–Ripken estate in this exurb of Baltimore, and there’s not much info in there at all. But the model of car that the would-be trespasser was driving is named in the report, and I got really excited when I Googled the name of that kind of car and Kevin Costner and immediately got a hit back that indicated that Costner loves Audis. It didn’t occur to me until we had our weekly call with the folks at Blue Wire that one of our producers pointed out that I might want to Google other luxury car brands and search for, like, Mercedes and BMW and Kevin Costner. And sure enough, it would seem he’s a fan of all of those very expensive cars.

What was the closest you both came to truly believing the whole rumor was true?

Montandon: For me, it probably would have been pretty early on in the reporting when I had a call with this sober-minded Baltimore attorney who knows Cal socially, and claimed to have good access to information and friendships and acquaintances with very powerful people, both in Baltimore and within the organization. And when a source like that told us he absolutely believed it was true — up until that point, I was extremely skeptical. And then from that point on, I was like, Well, if this guy, who’s in a great position to know such a thing — if he’s this certain, then maybe I need to ratchet up my level of certainty. It felt more reasonable to get very serious about the investigation.

Dingman: I would agree completely. I think that was the moment for me that felt the most like, This isn’t a lark. All of a sudden it very abruptly left the realm of the fun, sort of fizzy investigative la-la land and came kind of screeching into the realm of the plausible.

Besides the Ripkens and Costner, is there someone you really wish would have spoken with you but wouldn’t?

Dingman: Well, Randy Johnson [who plays a key role in the finale], obviously. But Brady Anderson’s a big one for me. He and Cal were such close friends, and I have a strong sense that Brady Anderson has a kind of friend intimacy with Cal and sees him as a person in the way that we came to see Cal as a person through doing this project, that probably isn’t shared by too many other folks.

Montandon: Mine is a guy named Richard, who was the Ripken estate manager for one single month: August, 1997 — make of that what you will. I really, really, really wanted to talk to him. The other person, purely because I adore him, was Baltimore native John Waters. We actually did get his email, and bless his heart, he responded to my crazy requests for an interview. But he is absolutely right — he would have been a terrible source for this, since, in his words, he knows nothing about Cal Ripken or the rumor and had never heard of a former cop named Mad Dog. But I still would have loved to talk to him just because, growing up, I remember being in high school and we would get flyers at my school to go to, like, open auditions for Hairspray. And if you watch his version of the film Hairspray, you can see a couple of my friends from high school dancing in the background. So he’s meant a lot to me for a long time.

Neither Ripken nor Costner agreed to talk with you, but they’ve both answered questions about the rumor in the past, denying it. Who do you think likes to talk about it less these days?

Montandon: I love that question. I love just thinking about them being home, like avoiding calls and texts. But I’ll say, based on what they have said in the past and the way they’ve said it — this is complicated, because Costner went on and on about it during a radio interview once, but he seemed really upset, and Cal was very brief on it during a different interview, but he was very calm. But I’m gonna go with Cal, just because he still lives in Maryland. He still has his whole life and legacy there. And I feel like ultimately, for him, it’s way more personal and with way higher stakes.

Dingman: I’m going to guess it’s the other way around, with the caveat that if we use as our gauge the vitriol in the responses from their official representatives, Cal’s PR team was way angrier about the question than Kevin’s was. But I tend to think fundamentally Kevin Costner’s work is more about persona than Ripken’s is. A persona is a necessity of being a professional athlete, but to less of a degree than when you’re a movie star, and Kevin Costner is still obviously active, doing lots of big, prestigious work. He’s still in the midst of his career, and while I’m sure there’s more to come for Cal and his professional life, it’s not as public facing as it once was.

The other thing is, whenever we had conversations with fans about the rumor, I would always ask them: If you were to find out that this story was true, would it change the way you feel about Cal Ripken? And to a person, everybody that we spoke to said, No, man, it makes me like him more. Like, Cal’s my guy. And if he was doing what he thought was the right thing in that moment, you know, I trust him, because I trust Cal. So I don’t know if Cal realizes that or if his PR team realizes that, but it seems like, you know, if it were to come out that the fistfight part of this story were true, it doesn’t seem like it would have too much of a drag on Cal’s reputation from the anecdotal conversations that we had.

This interview has been edited and condensed.