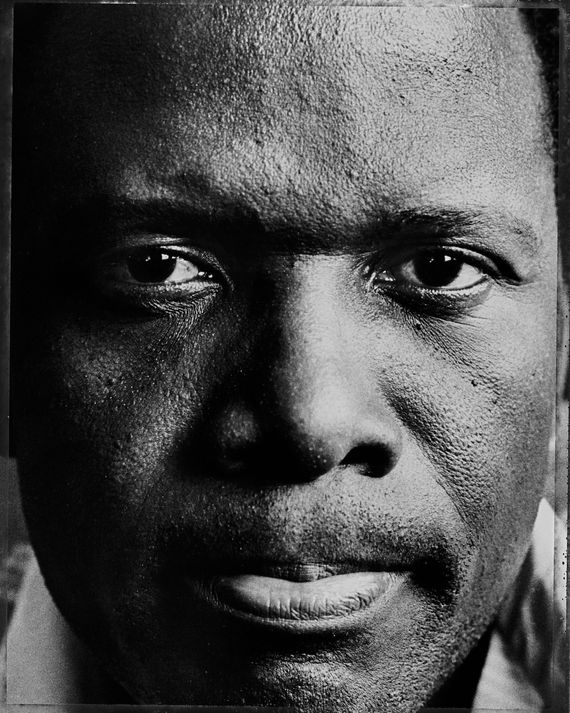

It’s 1974. My Afro and I are sitting on a bed with my mom, watching TV. On our black-and-white set is a very handsome, and very shirtless, Black man named Sidney Poitier. The movie is 1973’s A Warm December, a bittersweet romance starring Jamaican actress Esther Anderson and Sidney Poitier himself — maybe the first semblance of Black love I’d ever seen onscreen. Back on my side of the television, smoke was coming off of my mom’s pink foam curlers, seemingly thickest whenever Sidney’s doctor character took off that shirt. Which was often. “Put your damn shirt back on!” I thought. Boy, was I a fool.

If you are my age and had a Black mama, chances are good she had a thing for the late Sidney Poitier. When Denzel Washington, Sidney’s heir apparent, started rising in the ranks of film history, Mom said, “He’s cute. But he’s no Sidney.” Like Denzel, he belonged to Black folks so thoroughly that he was on a first-name basis. Honorifics were only necessary when referring to Mr. Tibbs, the police officer he played in the first cinematic trilogy featuring a Black character, or Sir, the Bahamian teacher he played in my favorite movie of his, To Sir, With Love.

But the Sidney I saw onscreen as a kid in the ’70s was not the Sidney my mother saw. I got him when he was firmly in control of his choices, both in front of and behind the camera. When he could cast his lifelong pal Harry Belafonte as a co-lead in his directorial debut and let him run off with Buck and the Preacher. Mom got him when the Hollywood system rarely had time for African American characters, unless they were playing a stereotype or singing and dancing. Unlike Belafonte, Sidney couldn’t sing to save his life, though that didn’t stop Hollywood from making him lip-sync in Porgy and Bess or sing Negro spirituals to nice little German nuns in 1963’s Lilies of the Field (for which he won an Oscar).

His debut in 1950’s No Way Out was a stunner nonetheless. Joe Mankiewicz and Lesser Samuels’s white-hot noir was about a Black doctor and the racist he must contend with after he’s accused of causing the white man’s brother’s death. Dr. Luther Brooks is afforded a righteous rage that, considering the time, must have been jarring for people to behold. Hell, the last line in the film is Sidney telling Richard Widmark, “White boy, you’re gonna live.” It would be years before my mom would see that boldness again, most notably when Virgil Tibbs slaps the taste out of a “respected” white man’s mouth in 1967’s In the Heat of the Night. Black audiences went batshit, and rightfully so. Tibbs wasn’t just slapping some white guy; he was going upside the head of an entire institution.

Between Dr. Brooks and Mr. Tibbs, Sidney earned a lot of firsts. He was the first Black man to be nominated for Best Actor at the Oscars (for 1958’s The Defiant Ones) and the first to win the award (for Lilies of the Field). In 1967, he became the first Black actor to sit at the top of the box office as the single greatest draw, his hits including that year’s Best Picture winner, In the Heat of the Night, as well as To Sir, With Love and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. The thing is my mother’s Sidney often got Old Hollywood–era parts that were designed to make white audiences feel comfortable with Black men onscreen, occasionally requiring that his characters suffer and/or die. That he was the first as well as one of the only actors permitted to compete for these awards was rarely acknowledged by a Hollywood too busy patting itself on the back.

Though Dr. John Prentice (yes, another doctor) doesn’t die or suffer in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, he is perhaps the nadir of this phenomenon, so flawless and sexless that even a Grand Duke Wizard would consider letting him marry his daughter. Yet Sidney’s performances managed to rise above a nagging sense of Noble Negritude. See his sexy flirtations with Diahann Carroll in 1961’s Paris Blues, his budding friendship with John Cassavetes in Marty Ritt’s 1957 debut Edge of the City, or his antagonistic back-and-forths with Tony Curtis in 1958’s The Defiant Ones. And in 1959, Sidney Poitier’s return to the stage begot his greatest onscreen performance when A Raisin in the Sun was transferred to film in 1961. As Walter Lee Younger, he helped usher through another first — the first major-studio release written by a Black woman, Lorraine Hansberry. (The character was so well developed on the page that not even P. Diddy could destroy the role decades later.)

It wasn’t until Gordon Parks kicked open the directorial door, and Bill Gunn, Ossie Davis, and Melvin Van Peebles ran through it, that my mom’s Sidney became my Sidney. That’s when he hopped in the helmer’s chair and made his own romances, a western, a murder mystery, and some very silly comedies. His 1970s output included other firsts, things mainstream audiences hadn’t seen onscreen before: disputes between Blacks and Native Americans in the Old West; recognizable neighborhood characters with names like Leggy Peggy, Biggie Smalls, Geechie Dan, and Madame Zenobia; and lusty, realistic explorations of Black people in love. Finally, Sidney could be funny, horny, petty, and even wrong. And he could do so without worrying he was setting a bad example. It felt like he had been returned to Black people, like the shackles of the White gaze unfairly imposed on him had finally been broken.

It all culminated in his later career, with roles in Sneakers (where he gets to cuss and be in the CIA) and Shoot to Kill, where we can sense a much freer actor. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that some of the things Sidney Poitier made were less glorious. (Sure, he directed Stir Crazy with Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder and Hanky Panky with Wilder and Gilda Radner. But he also directed Fast Forward and Ghost Dad, the latter of which is to his directing career what that dinner movie is to his acting career.) But no matter, a legend has left us, and he leaves behind a legacy of joy, awe, and inspiration. I now have a reason to bawl my eyes out when Lulu sings “To Sir, With Love.” Not that I didn’t bawl my eyes out before, mind you. It’s just a much sadder cry now.