Once upon a time in the early ’90s, Hollywood agents lived in the middle of the cultural conversation. Like the hypercompetitive wheelers and dealers portrayed in shows like Entourage or Call My Agent, agents were tasked with brokering agreements between clients (writers, directors, actors) and the studios and networks who hired them — agreements that were meant to be both financially rewarding and mutually beneficial to all parties involved. Although plenty of the time they were not quite either.

It was around then that Creative Artists Agency — led by its Art of War–quoting, bulldog of a chairman Michael Ovitz — began tilting the balance of power, aggressively assembling package deals that leveraged his firm’s expansive roster of A-list talent. By packaging a bundle of actors, or a writer and a director, together in one deal, CAA was able to arm-twist studios and networks into bigger paydays. The town’s other major agencies, William Morris and International Creative Management, were getting smoked in the process; absent the same roster of stars, they were unable to manufacture packages that could compete. It wasn’t a great time to be anyone but a CAA agent, but the CEOs of two relatively tiny rivals saw the smolder as an opportunity anyway. In 1991, the boutique Bauer-Benedek Agency merged with the similarly small-scale Leading Artists Agency to form an upstart alternative: United Talent Agency.

“We saw there was this opportunity to super-serve another generation of filmmakers and writers,” says original UTA minority partner Jeremy Zimmer. “Because at CAA it was clear: If you were a movie star or an A-level director you got all the attention and love. If you were anyone else, you were just happy to be part of the club. We felt there was an opportunity to treat our writers and emerging directors like stars. If we did that well, that could become the building block of the next major agency.”

UTA went on to launch a fresh-faced Sandra Bullock into the top tier of stardom and iron out Jim Carrey’s paradigm-shifting $20 million payday for The Cable Guy. As a start-up, however, the agency wasn’t immune to growing pains. Just a few years in, the talent house became something of a punch line among the other big agencies for rumors of in-fighting among its ranks that spilled uncharacteristically into public view. In 1996, UTA fired provocateur TV agent Gavin Polone, pilloried him in news articles, then gave him a $6 million severance package. Polone sued them in return, then the agency filed a lawsuit against Polone’s young associate Jay Sures after he attempted to get out of his contract, citing “intolerable working conditions.” Sures was ultimately promoted and today serves as UTA’s co-president. Indeed, it’s the stuff of prestige-TV plotlines.

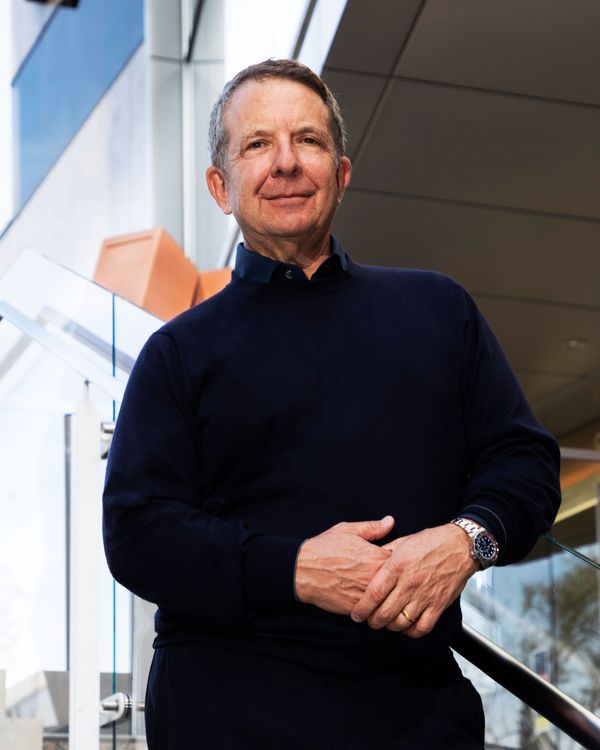

Over the intervening decades, the landscape of fame has dramatically shifted. Agenting has come to cover far more than just traditional “talent,” with new legions of pop stars, professional athletes, authors, supermodels, social-media influencers, broadcast journalists, reality-TV phenoms, e-sports superstars, and unspecified “thought leaders” demanding services from the ten-percenters. Just as United Talent Agency slips past its 30th anniversary in 2022, Zimmer, now long established as the firm’s chief executive and one of the industry’s preeminent power brokers, agreed to step from behind agenting’s abiding wall of silence to speak to Vulture about that milestone.

When we meet on an unseasonably warm winter morning on the second-floor patio of his UTA office, which boasts sweeping views of the Beverly Hills flats, he has agreed to address the past, present, and future of agenting. However, Zimmer cannot legally discuss the impending announcement of a first-of-its-kind talent-agency SPAC which will make United Talent Agency the only core business within the Hollywood entertainment community to jump into the white-hot Special Purpose Acquisitions Company space. This new venture allows UTA — which reps everyone from Timothée Chalamet and Lebron James to Charli and Dixie D’Amelio and Malala Yousafzai — to skip the regulatory hurdles and financial scrutiny that normally accompany an IPO and merge with a deeply funded blank-check company to become a publicly traded entity. One that specifically intends to raise at least $200 million to pursue the purchase of gaming- and e-sports-related businesses that UTA increasingly specializes in.

Zimmer agrees that agenting is at another inflection point. Last year saw Endeavor Group Holdings, the umbrella company behind Hollywood’s biggest agency, WME, finally list on the New York Stock Exchange in a dramatic recalibration of its ambitions. Then just a few weeks ago, the second biggest megafirm, CAA, shocked the show-biz brain trust by acquiring ICM — the other so-called “Big Four” agency — in a merger that marked a seismic shift in the representation business. Yet Zimmer is adamant that UTA’s strategy and self-image hasn’t changed all that much from its ’90s glory days.

“UTA was always about respecting and believing this writer could really become a great filmmaker or this cool young filmmaker could become an important world mover,” he says. “We’re not so concerned with stealing clients as developing clients. We try to treat our clients like the future stars they are going to be. And as a result, I think they get more attention from us than they do from some of our competition.”

In 2006, when most agencies were focused on importing traditional Hollywood stars onto nascent platforms like Twitter, UTA became the first to launch a dedicated division identifying internet-native talent. It became the first to launch a fine-arts division and one of the first with a podcasting division, as well as the first to launch a division dedicated to NFTs and digital assets last year. And on the heels of UTA’s acquisition of the e-sports companies Press X and Everyday Influencers in 2018, it is among the leading agencies representing streamers, game developers, and e-sport athletes.

Still, in the past decade, WME — headed by bomb-throwing CEO Ari Emanuel and decorously buttoned-up executive chairman Patrick Whitesell — has demonstrated a more voracious appetite for expansion. It acquired the global sports and marketing firm IMG for $2.4 billion in 2013 (reorganizing from WME-IMG to Endeavor in 2017), bought the Miss Universe Organization and the rodeo conglomerate Professional Bull Riders Inc. in 2015, and acquired the Ultimate Fighting Championship a year later for $4 billion. After scrapping its first IPO in 2019 citing market volatility (less charitable competitors cite overreach and greed), Endeavor finally went public in April. The already monolithic CAA, for its part, pulled off the biggest Hollywood shake-up in over a decade by swallowing ICM whole in October (the sale’s terms have not been disclosed and the transaction is still pending regulatory antitrust approval). Moreover, both Endeavor and CAA took on private-equity ownership a few years ago with TPG Capital and Silver Lake Partners respectively injecting over $1 billion dollars a piece in those agencies to take majority stakes. UTA, meanwhile, sold a “significant equity stake” to Investcorp and the Public Sector Pension Investment Board in 2018 but remains something of a Big Three outlier by maintaining its ownership.

When I ask Zimmer to break down how agenting has changed from the ’90s to the aughts to the teens, he launches into an overview of the many ways Hollywood has evolved as a content marketplace. According to Zimmer, the home-video boom — which began in the mid-1980s with an arms race between the two dominant formats, VHS and Betamax — ushered in a new era for independent film and an “explosion of demand and opportunity.” Suddenly it was no longer enough for agents to look to the usual suspects; smaller players such as Vestron, Alliance, and Lionsgate were getting cut in on the action that had once been the exclusive domain of Paramount, Universal, and 20th Century Fox.

Then, in rapid succession, came the cable and reality-TV booms of the ’90s. “Now you have got all these different cable players and their demands, their appetites. Now you have non-scripted clients,” Zimmer says. “It’s no longer something we all sneeze at. It’s a real business.” Wall Street came calling as a result, interested in funneling investment into agencies (ICM, for one, created a partnership with Merrill Lynch and Rizvi Traverse Management to finance films) in the mid-2000s. And then you have digitization. “At first it was as mundane as, ‘Oh it’s this weird YouTube thing.’ Then the web starts to proliferate,” he says, noting streaming and e-commerce as major developments that attracted new buyers and an “incredible” amount of financial resources. “There’s a million different ways that the web shaped things, right? To push a button and achieve global audience almost instantly,” he says. “But how do you create that audience? How do we use our celebrities and brands?”

But COVID-19 brought the momentum behind Hollywood dealmaking to a standstill in the spring of 2020. UTA was forced to furlough more than 100 employees with virtually all remaining staff accepting a pay cut; Zimmer and co-presidents Sures and David Kramer announced they would forgo any salary through the end of that year. (When quarantine conditions were lifted in the fall of 2020, UTA was the first agency to reinstate full pay for all employees.) Also that year: a devastating disagreement with the Writers Guild of America over packaging deals, those transactions that earned agencies additional fees from studios, networks, or streamers for bundling talent together for a particular show or movie which, as the Guild saw it, created financial windfalls for agents that were an unfair form of profit participation. The upshot: After a legal slugfest with the Big Four in April 2019, more than 7,000 WGA members fired their agents en masse. “It was a humbling time,” says Zimmer. “Our colleagues were losing clients who were dear friends; people they’d worked with for 25, 30 years were firing them. We were in a tricky, compromised position and we were uncertain about what it could mean for the future of our business.” Ultimately, UTA arrived as the first major agency to make peace with the WGA, striking a deal that “ends the practice of packaging” at the agency in June 2022 that ultimately compelled other agencies to follow suit.

Of course, the future of Zimmer’s business involves listing on NASDAQ under the ticker symbol UTAA, the special-purpose acquisition company signaling United Talent Agency’s emerging dominance in the rapidly proliferating e-sports and gaming marketplace. According to a source with knowledge of the company, UTA helped drive over $1 billion in gaming deals over the last few years. Under the agency’s head of video games Ophir Lupu, a team of a dozen agents now oversees around 100 e-sports and gaming pros. When questioned about where UTA stands with regard to the gigantic scale WME and CAA, Zimmer remains focused on that business. “I try to really admire what my competitors do well and avoid the mistakes they make,” the executive says. “I think the CAA guys inherited an amazing company and have improved upon it tremendously. And I think Ari has slammed together an incredible collection of assets.”

“We don’t need them to fall apart for us to succeed,” Zimmer adds. “In fact, the more they succeed, the more that success becomes a model for our success.”

After our conversation, UTA closed the biggest acquisition in agency history: a $125 million cash deal for MediaLink, an advisory firm that represents megalithic global brands including Coca-Cola, Lyft, Delta, and General Motors. Looking back, the deal makes sense in the scheme of things. “What we’ve been trying to do is expand and grow our capabilities so that if a client says, ‘I want to be a fine artist or I want to do a podcast or I want to write a book or I want to design a video game,’ we have the capabilities to help them do that,” Zimmer told me. (To that end, UTA has helped clients including Will Ferrell, Seth Rogen, and Chelsea Handler launch podcasts, and has arranged a showcase for singer-songwriter client Moses Sumney at Art Basel Miami.) “We’re always trying to figure out, How do we stay a step ahead of what the artists are doing?”