Werner Herzog is driving a car, with a nameless cameraman filming him from the passenger seat. “How many languages do you speak, Werner?” asks the cameraman in the manner of someone who has spent time with the German director and understands that even the most mundane question can provoke a poetic response of startling clarity and intrigue.

“Eh, not too many” Herzog says, a simple start to an answer that will soon run away from Werner, the cameraman, and anyone who’s watched footage of the moment on YouTube in the nearly 15 years since it was uploaded. The rest:

Spanish, English, German. And then I spoke modern Greek better than English. Once I made a film in modern Greek. But that’s because in school I learned Latin and ancient Greek. So from ancient Greek to modern Greek, it’s not that far. And I do speak some Italian, and I do understand French, but I refuse to speak it. It’s the last thing I would ever do. You can only get some French out of me with a gun pointed at my head or something like that; then I would speak French. It actually happened to me. I was taken prisoner in Africa. And drunk soldiers on a truck, all of them 15, 16 years old — some of them 8, 9 years old — and, I mean, really scared. One pointing a gun here, a Kalashnikov. Another one here, and another one there. So that was very unpleasant because they were all drunk, and some of the little ones were stoned. And I tried to explain that they probably arrested the wrong ones, and the captain of them shouts at me, ‘On n’y parle français ici.’ ‘Here we are speaking French.’ So I had to say a few things in French. I regret it. I shouldn’t have done it.

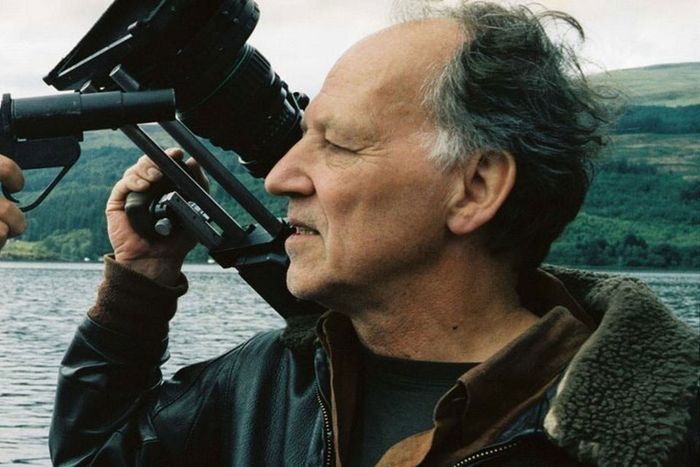

These 200-plus words capture the strange allure of Werner Herzog. Aside from directing over 60 genre-defining features and documentaries, he looks like an Arctic explorer and speaks like a potion seller from a role-playing game. He has the mien of someone for whom speaking innumerable languages is possible. This legacy has allowed a micro-industry of pastiche and parody to prosper, from Werner Herzog’s note to his cleaning lady to “Werner Herzog Reads Wheres’s Waldo?” all the way to Paul F. Tompkins’s seminal Werner Herzog review of a Trader Joe’s (which Herzog himself has approved). Real clips of real Herzog are even more popular. We have seen him declaim on the inanity of chickens, celebrate the genius of Nicolas Cage, and reveal he only just learned John Waters is gay.

But when I posted a clip of Werner waxing poetic on his grasp of foreign languages — which went briefly viral in 2020 and even prompted a Wikipedia user to update the “Personal Life” section of Herzog’s entry — someone replied with a cryptic quote tweet: “im not sure you can trust this, i think the clip is an outtake from a fake documentary.”

That fake documentary would be the 2004 film Incident at Loch Ness, written and produced by Herzog and Zak Penn, the cryptic replier himself. It’s a film I have seen and love in which Herzog features as “himself,” subtly exaggerating his reputation and propagating new myths along the way. (At one point he discusses a nightlong ordeal on a stranded boat being rammed by the Loch Ness Monster.) Taking in Penn’s tweet, I wondered if I, a discerning cinéaste drowning in delicious internet points, had fallen into a Herzogian trap?

“A lot of the movie is about Werner, but a lot of it is about making movies,” explains Penn, who, after our exchange on Twitter, agreed to speak to me over the phone. “It’s about trying to force yourself to ask what aspect of what you’re watching is real and what might be fake. Which seems like it may have caught up in our culture right now.”

In Incident at Loch Ness Penn plays himself, only this “Zak” is not the amiable screenwriter (whose credits include Last Action Hero, Antz, two X-Men movies, The Avengers, and Ready Player One) I found on the other end of the phone but a loutish producer who cajoles Herzog into making a film about the legendary Scottish sea monster. It’s a hilarious meta-commentary on fakeness and fakery grounded in two incredible performances: Herzog’s increasingly irate purist and Penn’s gleefully philistine boor.

“From the very beginning, it became apparent that the scenes worked better if I was less myself,” Penn says. “I tried to channel the worst impression you might have of someone like me. Part of it was I’d just come out of this project that I was supposed to direct that had fallen apart, and I realized I was channeling a lot of the people I had had to deal with, the notes that I had gotten, those circumstances. I decided, What if I was more like them — wouldn’t that be more interesting?”

And so, in what plays as an attempt to transform Herzog’s straightforward documentary on the alleged monster lurking in Loch Ness into a blockbuster movie, Penn performs the role of a Hollywood jerk, infuriating Herzog by, for example, hiring a cryptozoologist named Michael who later ends up dead. “One of my goals was to make a movie where you were constantly asking yourself, Is this real? Isn’t it real? If it isn’t real, why? Why would they do this?” he says. “It was just a subject that was always interesting to me.”

It’s also a subject close to my heart, for I, too, am a faker. Some years ago, I spent my time online creating Remembering Ireland, for which my friend Michael Murray and I would pass off fake farmer’s erotica, fake brochures for prison nuptials, and fake ephemera from a heavy-metal band made up entirely of Catholic priests as artifacts from an imagined Irish past. A few months before I shared the clip of Herzog, I discovered that one of these fakeries — a photograph purporting to show Noam Chomsky and an elephant present at a riot in Belfast — was being presented without irony on a pub wall in Belfast. I rejoiced in the credulity of others only to feel the sting of comeuppance not long after.

“What’s funny was when people saw the movie, the first wave were pretty angry with me,” Penn recalls of Incident at Loch Ness’s release. (Not even Roger Ebert definitively called the film a mockumentary in his review.) “I mean, clearly, you can see that I directed the movie. So of course I couldn’t possibly be that stupid to make a movie that made me look so bad! It was fascinating. They’d ask angry questions, and I’d have to be like, ‘Guys, that didn’t happen. My friend Michael is still alive, and Werner is not really angry.’ I was pretty happy with that, that it confused some very smart people.”

Part of the confusion, I offer — perhaps to remedy my own embarrassment — might be down to just how convincing Herzog is in the role. Early in the film, he shows Penn around his house, presenting an array of objects he’d picked up on his travels. I tell Penn that these are exactly the sort of things I could imagine Herzog having in his home.

“That stuff is real!” he says. “But the house isn’t real. It’s actually my house. I picked up all his stuff. I said, ‘Bring the spears, bring this,’ and we used it as set design.”

“In terms of factual truth,” Penn adds, “almost everything Werner says in the movie is something he said to me before or during filming, and I’d say, ‘Oh my God, that’s great,’ and take some notes down. I had a whole list of true stories he’d told us beforehand.” So was the story of tiny, drunk hostage-takers persuading Herzog to speak French against his will among those true stories?

“I mean, I’ve heard him speak those languages. His attitude toward French is what he says. I didn’t make that up,” he replies. “You’d have to ask Werner.”

“Hello. Can you hear me?” asks a black screen on my laptop. I am using Zoom for the 4,000th time since the beginning of the pandemic and enjoying approximately the 4,000th technical glitch in the same time period. A few seconds later, Werner Herzog bursts into view, his familiar face framed by bookshelves and sliding drawers, which I long to believe contain a spear and the animatronic prostheses of a fully working Loch Ness Monster. For 20 minutes, I withstand the ego-shredding horror of a five-second delay in video communication, which leaves my every question stranded in total silence as if the stupidity has rendered him dumbstruck.

“He’s actually a pretty down-to-earth guy,” Penn coaches me ahead of the call. “I had Werner and Lena” — Herzog’s wife — “over the week before last, and we made ribs. He likes to come over for the Super Bowl and drink cheap beer, and you have to serve him [adopting a Bavarian twang] ‘thih reeal Ameriiican chips, the baaad kind.’ “He’s not like the film version of himself, constantly dropping crazy extreme things, although it doesn’t take long before he’s talking about being on the slopes of a volcano in North Korea because that’s where he was last week.”

Herzog and I first discuss the objects he shows Penn in Incident at Loch Ness. “They are not spears; they’re arrows,” Herzog says. “They’re six feet long and shot like javelins by natives in the rainforest in Amazonia. They use it mostly for fishing — an arrow that long stays straight when it penetrates into the water; it doesn’t wobble. So Zak liked it, and I brought it as a prop.”

According to Herzog, the overall film came together in a similarly effortless way. Penn sent him a screenplay and asked if he would play a part, and Herzog said yes. “It looked intelligent. I had the feeling that a little bit of self-irony would be good for me. The whole thing was interesting, how it plays with various strata of invention and facts and quasi facts, and of course nothing is truth. All is invented. And you will know it in five minutes flat when you watch the film.”

This wasn’t the case for some of those early audience members, I counter. “Which is beautiful! It only shows the borderline where stupidity begins,” Herzog says. “You see these reviewers who would lambaste Zak — they are simply stupid, that is it. It’s a simple borderline that shows you that no culture of film reviews anymore. All has shifted into celebrity news.”

Feeling increasingly stupid myself, I bite the bullet. “Werner,” I ask, “were you really held at gunpoint and made to speak a few regrettable sentences in French?” Is the story you tell in the Incident at Loch Ness outtake real?

“No,” he says. “Look, I do speak those languages, sure. I mean, I do not speak Latin or ancient Greek because they are dead languages, but I can read them. It’s of minor importance; as always, there’s some layers, few facts, a few distortions. It’s inventive. I do have fundamental problems with speaking French because I am very Bavarian, and it’s a very different attitude to spoken language or discourse. Discourse is different from French. I did have to do with child soldiers in Honduras and Nicaragua for one film. I’m actually planning a project in Sierra Leone with child soldiers — completely staged, of course — but it concerns some U.N. troops and a small group of child soldiers who hold a checkpoint at a bridge. So, of course, child soldiers have always had a certain appeal to me because something deep comes across there.”

Perhaps sensing my dejection at his runaround answer and the end of our allotted time together on Zoom, Herzog launches into an unbroken paean to fakery’s favorable position over the so-called truth, citing the French Nobel Prize winner André Gide and William Shakespeare, two figures who’ve expressed a preference for feigning. “Only those who are deeply religious would tell you what the truth is,” he says at one point. “And they are obviously as wrong as it gets because the biggest of all fake news is religion.”

And what of this outtake, I ask. Is it not itself, for all the joy of its execution, merely fake news of the same order?

“I always quote Michelangelo as my key witness” he replies, “whose Pietà is in Rome. When you look at the statue, you see the dead body of Jesus in Mary’s lap. Jesus’ face is the tormented face of a 33-year-old man. And when you look at the face of his mother, she is 15. So my question is, Did Michelangelo try to cheat us? Did he try to give us fake news? Did he try to defraud us, lie to us? No. I think he made a clear statement.”

Séamas O’Reilly’s childhood memoir, Did Ye Hear Mammy Died? — which is funnier than the title makes it sound — will be published by Little, Brown on February 22 and is available for preorder now.