For casual observers of the artist formerly known as Kanye West, the rapper–producer–tabloid fixture–billionaire apparel magnate’s two-decade ascendancy as hip-hop’s most polarizing and galvanizing figure has become inextricably linked with certain grand — if erratic — gestures: swiping the MTV Video Music Award from Taylor Swift. Proclaiming President George W. Bush “doesn’t care about Black people.” Hitting up Mark Zuckerberg for a billion dollars on Twitter. And, of course, running for president (just months removed from donning a MAGA hat). The episodic Ye documentary Jeen-Yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy (which arrived in 1,100 movie theaters across North America on Thursday before beginning streaming via weekly installments on Netflix February 16) provides something of a corrective to that view. Call it a portrait of the artist as a young firebrand.

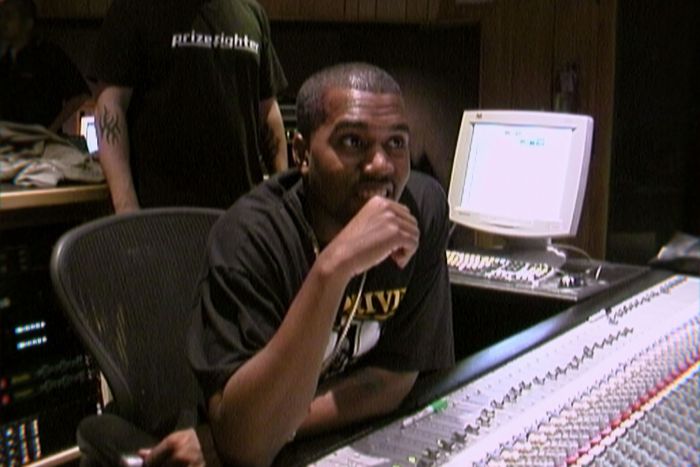

Largely shot over the period before West was a household name — before Ye had a record deal and at a time when he was still a freelance beat-maker who basically no one in the music-industry firmament believed could rock a mic — Jeen-Yuhs provides a startlingly intimate portrait of his uphill climb toward superstardom. The film’s fly-on-the-wall camera accompanies West to the studio the first time he raps on a Jay-Z track and follows Kanye into the dentist’s chair to have reconstructive surgery on his wired-shut jaw in the aftermath of a devastating car accident. It pursues him through the New York offices of Roc-A-Fella Records as Ye forces execs such as Chaka Pilgrim and Biggs Burke to listen to a demo tape that would establish the basis for his 2004 debut album on the label, The College Dropout. Most illuminatingly, the camera hones in on West’s singular relationship with his college-administrator mother Donda West: the drivetrain behind his creativity, ambition, connection to a higher power, and world-beating confidence (Donda died of complications surrounding cosmetic-surgery procedures in 2007).

But as filmed by West’s Chicago confidante Clarence “Coodie” Simmons Jr. (and co-directed by his longtime creative collaborator Chike Ozah), the docuseries’s meta-narrative also details the uphill battle of getting any kind of Ye documentary into the public realm. Coodie says he was inspired to chronicle West’s journey after watching the award-winning 1994 basketball documentary Hoop Dreams. In Jeen-Yuhs, he is shown dedicating years of his life to trailing West from meeting to meeting, from performances to after-parties to awards shows to recording sessions — arguably helping the artist land his recording contract by creating the kind of mystique that came from fixing him with a filmic gaze — only to be exiled from West’s inner circle after the rapper-producer finally topped the pop charts.

Moreover, West actively suppressed the documentary’s release when Chike and Coodie began maneuvering to assemble the footage around 2006. “I’m like, Okay, let’s put this out now because there was a deal on the table to do it,” Coodie tells Vulture. “But Kanye didn’t want nobody to see that side of him. Now he’s a super-huge star and he knows people look at him in a certain light. He wanted them to continue to look at him in that light.”

And in a now-deleted Instagram post on January 21, Ye demanded oversight on Jeen-Yuhs ahead of its premiere at the Sundance Film Festival — never mind he had already promised the directors full editorial control. “I’m going to say this kindly for the last time,” West wrote. “I must get final edit and approval on this doc before it releases on Netflix. Open the edit room immediately so I can be in charge of my own image. Thank you in advance.” West followed that missive up with another since-deleted post on February 7 indicating he wanted a certain Toronto-born frenemy “to do the narration” for the film — which West admits he still has not seen.

West and Coodie ultimately reconciled in 2017, prompting the director to resume the documentary process, accompanying Ye on a series of excursions to China (to record an album with Kid Cudi), the Dominican Republic, and his sprawling creative compound in Cody, Wyoming (Justin Bieber was there). But during an absurdly short Zoom interview this week, I asked the Jeen-Yuhs co-directors what compelled West to suddenly demand final cut — and whether he had any right to even ask for it. “Well, you know this movie wouldn’t be so anticipated if Kanye wasn’t Kanye,” Coodie says with a chuckle. “When I seen that he wanted final cut, it was a bit disappointing because we [were] in the bottom of the ninth with this film coming out in theaters on the 10th. But like I told him, this is not the definitive Kanye West documentary.”

“This is a doc about a journey that me and him took and we’re using this journey to show that everybody has an inner genius,” he continues. “We had a rough cut of the movie when I went to [visit him in the Dominican Republic] and I only showed him the sizzle [reel], but he wanted to put that out then. And I told him that he could not be involved creatively. Because that takes away the authenticity. And I told him the story that we’re telling is this story. It’s not about making you look a certain way. This story is about showing these dreamers that they can have a dream and make it.”

“So for him to say that … that’s just Kanye.”

That Jeen-Yuhs is not the “definitive” West doc becomes particularly clear in the series’s third installment. During a sequence shot at a lush seaside mansion in the Dominican Republic, the rapper-producer — who has described bipolar disorder as his “superpower” and was put on a 5150 involuntary psychiatric hold for mental-health issues in 2016 — is filmed becoming increasingly agitated during a conversation with billionaire investor Michael Novogratz and newspaper columnist Dan Barry. “Have you guys ever been locked up in handcuffs and put into a hospital because your brain was too big for your skull? Okay, I have,” West says in the doc. “There’s an execution style that was performed on me over the past six to seven years, post–Taylor Swift. Where they tie one arm — both arms, both legs to four horses all in different directions. Boom! Bah!” In what might have otherwise been one of the series’s more sensational and revealing moments, however, Coodie stops filming and puts the camera down.

The director says he was familiar with what had become known as West’s “rants”: off-kilter diatribes such as the performer’s 15-minute filibuster from the stage in Sacramento during his Saint Pablo Tour, during which he went in on Barack Obama and terrestrial radio (“Hey radio, fuck you!”), accused Jay-Z of dodging his calls, and pleaded with DJ Khaled not to send “hitters from Miami” after him. But Coodie says he was unprepared to witness what seemed like West’s mental unraveling firsthand. And as he explains it, ceasing recording wasn’t so much a dereliction of his duties as a documentarian as it was his in-the-moment choice to protect a buddy.

“It was crazy. Not crazy — it was just like, tripped out to me to be filming it,” the director says. “Not for nothing, Kanye’s like my brother. No matter what we went through in life, and the separation and all, he’s still a brother to me. And I love him like a brother. So I wanted to pay close attention and make sure everything was okay. So that’s why I put the camera down. That was just me knowing I needed to pay attention and see what’s going on so I can intervene if I need to.”

So you chose friendship over filmmaking, I offer.

“Brotherhood over filmmaking,” Coodie says.