Concerns about “goodness” might very well cross your mind as you watch David Mamet’s American Buffalo, now at the Circle in the Square Theatre. As intrusive thoughts assault you — say, worries about whether the playwright’s public pronouncements have just triggered a war on teachers — it can be useful to return to basics. A good knife, said Aristotle, is one that cuts. So, are the performances good? They are! Sam Rockwell and Laurence Fishburne, and to a less spectacular extent, Darren Criss, are clearly reveling in material worth their impressive stage mettle. Is the production good? Oh, certainly — it holds up Mamet’s 1975 text like a coin, making it wink in the light. But is the play good? There, now, there you have me. Because American Buffalo works as it used to work (or at least every time I’ve seen it) as a vivid comic indictment of warped American posturing and language. It’s just that now we wonder — given its creator’s wild fall from sense — if its raillery might also have some other function.

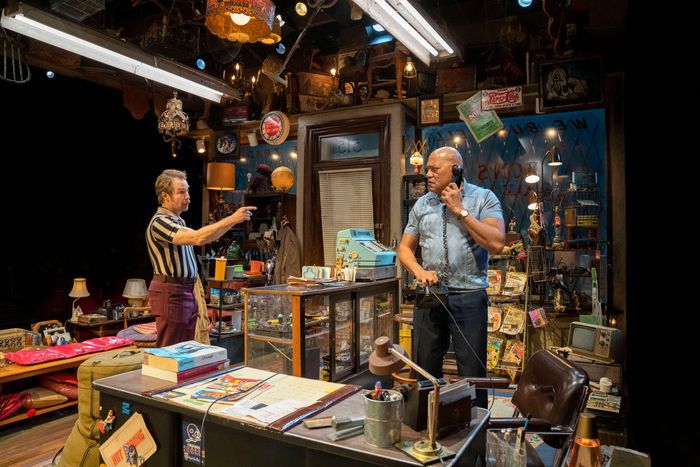

People are always touching and adjusting the stuff in Don’s junk shop — you would too if you could get onstage. Scott Pask’s set is jammed full of lacrosse sticks, lamps, boxing gloves, tennis rackets, hand weights, baseball bats, mannequin heads — all the stuff you want to pick up and put down without buying. Don himself (Fishburne) is tactile; he has his wad of cash always ready, caressing it and peeling off bills for Bob (Criss), his runner and trainee. Don’s patient attempts to teach Bob are hampered both by his own lack of wisdom — when Don says something’s friendship, it’s always business, and vice versa — and Bobby’s cotton-between-the-ears dimwittedness. Just sending the kid to the diner for an order takes several trips, but Fishburne swims gracefully through his jumble shop like a shark in a tank; he never rises to anger.

Don has a long, long fuse, but the neighborhood knucklehead wants to light it. As the play’s impish fire-starter, Rockwell’s over-caffeinated Teach cannot keep his hands off the merchandise. As he strides around (costume designer Dede Ayite puts him in plaid pants so vile they almost do the striding for him), he puts on the gloves to shadowbox; he picks up the weight to do some curls. He’s particularly drawn to the poker table, where he and Don lost a bundle to their friends the night before. The resentment over those losses has Teach hopping mad, hurling slurs at Ruthie across the street — “dyke cocksucker,” he calls her, exquisite in his inaccuracy.

Don eventually reveals that he wants Bob to rob a guy for him, after a deal over a Buffalo nickel made him feel, well, buffaloed. Teach elbows Bob out of the deal, and then the comic mayhem gets underway. For all the foul language and brandished weapons, we’re in the land of classic comedy here. Orders for coffee turn into “Who’s on First”–style routines; there’s a bit of business with a telephone that could have been lifted from Nichols and May. Mamet in 1975 was pulling from a particularly jam-packed grab bag: Teach is like a Restoration comedy figure, a Mr. Malaprop, always saying he’s calm when he’s mad — he’s the key to the way the play uses language to mean its opposite. (The more these guys talk about pulling a job, the more you realize they will never pull the job.) You can look at American Buffalo as Mamet’s Waiting for Godot, or you can read it as the comic precursor to Glengarry Glen Ross, his richest, best-disguised tragedy.

Director Neil Pepe put together this production back in the pre-COVID days, and while back then there was a little Rialto weariness at the choice to bring back a much-revived play, it seemed of a piece with American theater practice. The choice has seemed stranger and stranger, though, as the last few years have unfolded. Still, there have been two or three generations of actors who, when they get to a certain point in their careers, use their marquee muscle to get a part in a Mamet. And who are we to deny them? It can go okay, when they rally for another Glengarry; it can go poorly, as it has with … several of Mamet’s whinier efforts.

Judged as a showcase, American Buffalo works beautifully. Rockwell has exactly the right tools to crack the Mamet safe. His half-whine, half-growl voice sings in what Todd London evocatively called the writer’s “fricative riffs” — unsurprisingly, given how well he’s suited to other writers of masculine lyric like Martin McDonagh. Fishburne, judging his rhythms to the nanosecond, grips the play and captains it, and it’s lucky that the close quarters of Circle in the Square allow you to see the details of his casual command. Criss, too, does fine work as the play’s slow-minded straight man, though he finds fewer details in his character than the other two men.

But there’s a world outside Don’s junk shop, and plays aren’t only showcases. Whenever I could lose myself in the dusty aisles with these violent buffoons, I could forget that. But for the most part, I watched American Buffalo with my heart in my throat, looking for evidence of the way its author would eventually break bad. There are clues, I suppose, but only ones that show up in hindsight: We couldn’t have known that a man who found comedy in language that sounds like talk but doesn’t mean anything would eventually fall for the sound of thuggishness himself. We shouldn’t ask plays to be barometers or diagnostic tools, so if you want to enjoy this finely made production, put all this noisy stuff out of your mind. I’m only telling you I couldn’t. Out in the lobby of the Circle in the Square, there is a rather sad-looking taxidermied buffalo. He’s standing at a slight tilt, marooned on a maroon carpet, looking cross-eyed at the line for the bar. I saw him as I headed in, and I thought, Poor dear, you were noble once. I found myself thinking exactly the same thing when the show began.

American Buffalo is at Circle in the Square.

More theater reviews

- Launching Into Adulthood, With Frenemies and Hummus: All Nighter

- Where’s Willy? Abe Koogler’s Deep Blue Sound

- Sumo Is a Subculture Story That Goes Big