Alex Garland’s latest feature, Men, is a sinister descent into a chthonic nightmare world disguised as a posh English country estate — where ancient forces engage in violent cycles of death and rebirth. The film is laden with resonant symbolism but evades simple interpretation; put plainly, it’s a real mindfuck. Garland isn’t inclined to dig too deeply into what it all means — for his benefit or that of his audience. “In my mind, I’ve got my own sets of preoccupations, and I don’t particularly bother to explain them or go through them too much,” he says.

While Garland believes that the audience’s interpretation of Men is more important than his own, he has laid out a few bread crumbs for viewers curious about the film’s influences. Some are fairly literal: Hajime Isayama’s hit anime, Attack on Titan, for example. Or the sad-sack ’90s rom-coms of screenwriter Richard Curtis. Others are more abstract — the “impossibility of objective truth” kind of abstract. In the dark woods where these strange and terrifying men dwell, dreams are reality, catharsis is a lie, and the old gods demand sacrifice. Below, Garland describes some of the images and influences that shaped Men.

Attack on Titan

One thing that struck me about Attack on Titan was that it wasn’t presenting nudity in the typical way. Usually, when nudity is seen in film, statues, or art, there’s been some consideration to it. It’s been posed. The Titans are terrifying and strange but also the sort of awkward shapes that people make when they’re not being observed.

The other thing I liked about Attack on Titan was that it made a couple of intelligent changes, then really followed through with them. Instead of trying to add bat wings and horns and ten arms or whatever, the movie took everyday people and slightly caricatured them. Some are more extreme, of course: One is skinned and another looks like an ape with fur and these very long, thin arms. But most of the Titans are drawn like political caricatures that you might see in a newspaper. They’re massive and don’t have genitals and all that, but it’s these quite subtle shifts that turn them into monsters.

It’s a bit like when you’re in an edit and there’s a very handsome actor onscreen. You press pause. He’s in mid-blink — one eyelid slightly lower than the other. His mouth is hanging open in a strange way. Suddenly, he’s not a handsome actor; he’s just a human being.

The Green Man

I first wrote a script with the Green Man in it about 15 years ago. I would periodically do research or drive up to a church that had one. The more I started being aware of them, the more I realized how common they are. I was walking down a street that I had walked down thousands of times and, suddenly, realized that three of the houses had Green Men in the eaves stones above the doors. One thing I found is that, particularly from about the ’60s onward, there was a neo-pagan explanation ascribed to these images. Quite often with the Green Man, they made him benign. He became a kindly forest god.

I’d look at the carvings and think they looked angry — like they’re screaming in pain. And I thought, I’m not going to go with a benign, cuddly Green Man. I’m going to go with a thing that I can feel in these carvings sometimes, which is anger, and not make an assumption that green is full of goodness.

As with all things, you’re learning more about the person doing the interpreting than about the thing itself. One of the things I’m interested in with this film is the nature of how things get interpreted — whether it’s a bit of old iconography or human behavior. I’m feeling skeptical about that at the moment.

Richard Curtis movies

I don’t mean to take a sideswipe at Richard Curtis in particular, but there’s a bourgeois sensibility in his films and a kind of mythologizing: Attractive people in attractive worlds that are broadly benign and do not get invaded by the spiky difficulties of reality.

I remember watching The Wonder Years when I was younger. I always used to look at the lawn outside the house and think, God, how amazing. A beautiful, green, perfect lawn. There was something hypnotizing about it. Seductive. So while I find a film like Notting Hill to be, yes, very bourgeois and problematic in some ways, I’d like to be there, you know?

I wanted the countryside and the house in Men to have that bourgeois reassurance about it — that comfort zone. It’s aspirational. Somebody really does have a house like that. Someone really does have a garden like that. And for Jessie Buckley’s character, Harper, it’s like, This is perfect. This is what I dreamed it would be. This is a place where I can be comforted, process, and get better.

Surrealism

Everything is surreal, and pretty much everything is open to interpretation. Lawyers and judges — their professional lives are based around the interpretation of sentences. Laws are written to try to be clear, but we argue about their meaning incessantly. And human life, as far as I can tell, is much more dreamlike than not. Encounters are surreal. Other people are surreal. Things that happen to us in the course of our everyday lives have a deep strangeness to them.

We live in a much more imaginative space than we think we do. We experience the world through our eyes and ears, and we have to make ourselves believe that we have an objective understanding of what we see — so we can just go about our day and talk to our work colleagues and buy some food at the shops. We have to believe that’s all objective. But we are all disagreeing constantly, strongly about almost everything, so clearly it’s not that objective. I’m not trying to get bogged down in a discussion of what constitutes truth — I think there is a thing that you could call truth, but I’m not sure we are the best things to judge it.

I just think life is strange, and I’m trying to reflect how strange life feels to me. I don’t feel that life is predictable and comfortable. It’s often unsettling and surprising, and it leaves me feeling uncertain about what is happening and why. That feeling, I don’t know what is happening or why, probably happens to me several times a day. It always feels like surrealism is actually a pretty fair way of presenting a story.

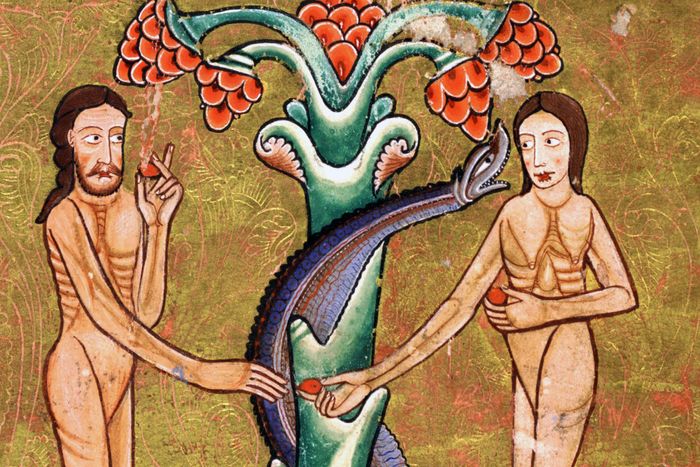

Adam and Eve

I wanted to give the film a sense of something that’s both fantastically old and fantastically present. It would be incredibly disingenuous to propose that the subject matter in this film is a modern phenomenon. I’d say it’s not about original sin so much as these are the flickering touchstones in people’s minds when they think about the subject.

I know that if I put that imagery in there, some people will think this is a Genesis allegory. But if the social-media phenomenon has taught us anything, it’s not to bother trying to make everyone agree; you’re wasting your time. In a funny way, it’s pushed me further toward — I’m just going to say this the way I think is the right way to say it.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.