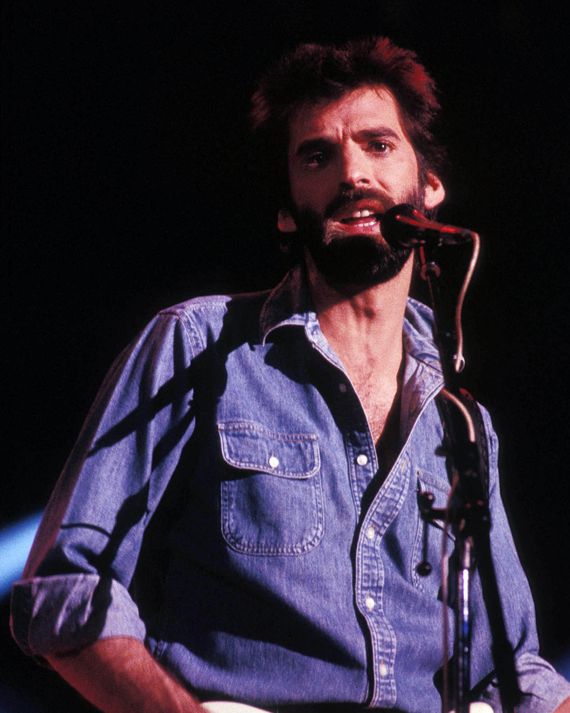

Kenny Loggins had yet to be crowned the King of ’80s Soundtracks when Dean Pitchford came calling. The Broadway vet was working on the script for Cheek to Cheek, a movie about a town that had banned dancing, and was hoping Loggins would write the music. At the time, Loggins was mostly known for his soft-rock stylings in his duo with Jim Messina as well as a handful of breakout solo hits. But he was more than willing to branch out, having written the anthemic “I’m Alright” for the 1980 comedy Caddyshack. When it became a top-ten hit, Loggins began fielding additional movie offers, including Pitchford’s soon-to-be-renamed Footloose and another era-defining dance film: Flashdance. Loggins netted only one of the two gigs, but it was more than enough: The title track to Footloose not only scored him his first and only No. 1 slot on “The Hot 100,” but it became one of the most popular singles of the decade. (By the time Loggins landed “Danger Zone” on the Tom Cruise vehicle Top Gun, his soundtrack reputation was solidified.) Of course, the story behind making “Footloose” — as the 74-year-old singer details in this exclusive excerpt from his forthcoming memoir, Still Alright — isn’t quite as straightforward as kicking off your Sunday shoes.

Excerpt From ‘Still Alright: A Memoir’

The soundtrack song everyone remembers, of course, is “Footloose.” My “Footloose” story doesn’t start with Footloose the movie, however, but with another iconic film from the early 1980s: Flashdance.

Flashdance was set up perfectly for me. It was produced by Jerry Bruckheimer, who I knew was a fan of “I’m Alright.” The film’s musical director was Phil Ramone, the producer on Celebrate Me Home. I was one of their first calls. When Jerry brought me to his Hollywood office and showed me a rough cut on his Moviola, I got excited. Back then, anything Bruckheimer touched was gold. I’d loved my experience with Caddyshack and was eager for another shot at a soundtrack.

What I came up with was the melody for a song I called “No Dancin’ Allowed.” Problem was, I was about to go on tour and wouldn’t have time to record it properly for a couple of months. That didn’t suit Jerry’s timeline, so I regretfully had to withdraw.

Then fate intervened — if one chalks up poor stage management and my own clumsiness to fate.

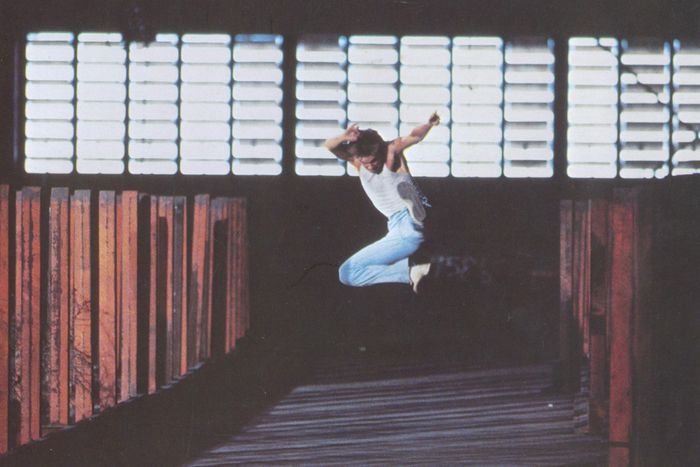

One of the first stops on my itinerary was the sports arena at Brigham Young University in Salt Lake City. The stage was about ten feet off the gym floor and, before the lights hit it, completely in the dark. I was up there just before showtime, walking around to my normal entry spot from stage left. Well, there wasn’t quite as much stage left as I expected and … let’s just say that ever since, if it’s dark onstage, I don’t take a single step until someone shines a flashlight onto the floor.

Yep, I fell right off the side of that goddamned stage and landed on my back atop some gear crates, breaking three ribs. I couldn’t move, and nobody heard my calls for help because the room was so loud with the crowd chanting, “Keh-NEE, Keh-NEE, Keh-NEE!” In my memory, it was quite the Shakespearean moment: the star dying as the audience screams his name.

I must have been down there for five minutes before somebody found me and I was helped back to the dressing room and then via ambulance to the hospital. My lungs were badly bruised and exquisitely painful, but luckily they hadn’t been punctured by my broken ribs. Needless to say, the show was canceled. Then the entire tour was canceled.

I was hospitalized for two days until it was safe to fly home. Even then, I had to borrow a plane from one of the Osmonds (Donny, I think) because I couldn’t sit up in a commercial jet. Once I got back to California, I crawled into bed and stayed there for weeks. (We did a make-up performance at BYU several months later, and I had three nurses escort me onto the stage. That went over pretty damn well.)

I managed my pain with a supply of Percodan prescribed by the doctor in Salt Lake City. Wow, did those pills work — maybe a little too well. I felt fine in no time at all, even though I was actually pretty far from fine. I knew I couldn’t sustain a tour in my condition, but thanks to those painkillers, I figured I could at least do a little studio work. So I called up Bruckheimer’s office. “Guess what?” I said. “I’m available again!”

I went to an L.A. studio to record “No Dancin’ Allowed” on Bruckheimer’s dime. Unfortunately, Percodan and I produced the thing together. I was popping it around the clock, and it affected my judgment more than I realized. Without so much as a run-through, I ended up cutting the song in the wrong key and couldn’t hit the high notes. There’s no explanation for it beyond my inability to think straight. I should have either gone back and rerecorded it or brought in some famous female vocalist to handle the high stuff and turned it into a duet. But I didn’t do those things, or anything else. Once I saw how unsuited I was for the instrumentation we’d put down, I didn’t end up recording a vocal track at all. Redoing the whole thing from scratch was too daunting; my injury had caught up with me and I was exhausted, so I just gave up. I still think of Flashdance as the one that got away.

That soundtrack ended up producing two No. 1 singles and was the album that finally knocked Michael Jackson’s Thriller from the top of the charts. And to think that for want of a sober co-producer, I could have been part of it. Not that I’m complaining.

Lucky for me, Caddyshack was opening all kinds of doors, and it wasn’t long before another soundtrack proposal landed on my desk. Dean Pitchford was a Broadway veteran who had won an Oscar for the theme song to Fame. He wanted to break into screenwriting and was working on a script about a rural town that banned dancing. He called it Cheek to Cheek, a placeholder title designed to be so intentionally awful that nobody would fall in love with it and decide to make it permanent. Dean said that he, in addition to writing the script, wanted to direct the project’s music and asked me to help him with the score. He called my sound “uniquely American” and praised my material’s relentlessly upbeat nature. He said he pictured me as the musical equivalent of the lead role.

That all sounded pretty good, but before I committed to a multi-song project, I figured it’d be best to give us both a little test to see how well we worked together. I gave Dean a cassette of a melody I’d been working on with Steve Perry to see what he could do with it. The words were just la-la-las except for the chorus: “Don’t fight it.” Nothing in the verse set that up, and nothing else in the chorus completed the thought. I left all of that up to Dean. I figured that if I liked what he came up with, I’d be much more inclined to sign on to his movie project.

Well, I liked it so much that I ended up recording the song with Steve and used it as the lead track on my High Adventure album. “Don’t Fight It” ended up nominated for a Grammy, which helped cement Dean’s standing with the folks at Paramount when it came to entrusting him with their soundtrack.

By that point, Dean had written enough to show me what he was doing — the name Cheek to Cheek had by then been changed to Footloose — and I grew enthusiastic. I was about to leave on tour and told him that if he came to meet me on the road, we could make significant progress before I returned home.

That’s when I cracked my ribs.

This threw off Dean’s schedule. First, I was laid up and in no shape to work. Once I found my bearings, I dedicated myself to finishing “No Dancin’ Allowed” for Flashdance. Dean and I had made some progress — we’d been trading ideas over the phone and via cassettes I kept sending him — but we wanted something in the can by the time I left for a winter tour of Asia. He said if he didn’t come back with at least 80 percent of the title track for the execs at Paramount, they might make him look for somebody else to work with. By that point, we were limited to only a few days during a weekend engagement I had in South Lake Tahoe — some warm-up shows before I departed the continent. If we didn’t get something done there, the work would have to wait for a couple of months and I might be off the project entirely. So Dean booked a room in the hotel where I was playing, and we scheduled as much time together as we could.

Trouble was, Dean was already pulling 20-hour days writing the screenplay and lining up musicians for the soundtrack, and the wear was beginning to show. He started to get sick before he left Los Angeles, and by the time he hit the snowy Sierras, he found himself with a serious case of strep throat.

Dean knew the last thing I wanted on the eve of an international tour was to be exposed to a respiratory ailment, so he hid it from me, gobbling whatever medicine helped him appear healthy during our writing sessions. He must have used Chloraseptic spray by the gallon. I didn’t learn that part until later, of course.

Somehow he pulled it off. For three consecutive days, we spent hours together in his room, fully developing the song “Footloose.” I was inspired by Mitch Ryder’s “Devil With a Blue Dress,” which had exactly the kind of groove I was looking for and opening bars that are about as classic as rock and roll gets. Dean helped integrate the script into our lyrics. I never would have thought of a line like “Kick off your Sunday shoes,” but Dean knew that Ariel’s father was a preacher — it was key to the movie’s primary conflict — and that line became a great reference. Dean brought in a ton of ideas like that.

The part that lists all those names in rhymes — “Please, Louise,” “Jack, get back,” “Oowhee, Marie,” “Whoa, Milo” — was inspired by Paul Simon’s “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover,” with its classic refrain: “Slip out the back, Jack / Make a new plan, Stan …” I always thought that was a fun lyrical trick, and it was only a small hop to “Please, Louise, pull me off of my knees.”

By the time I left for Asia, we’d finished everything but the bridge. Dean, finally able to let down his aura of invulnerability, went to a local emergency room to get treated before he returned home the following day. He really must have been in bad shape. His ploy worked, though; based on everything we’d done in Tahoe, Paramount execs agreed to his musical plan.

Initially, Dean wanted to use a demo of the song on set while they filmed. Many movies don’t even use music during dance scenes, to give the editor maximum leeway when it comes to utilizing dialogue; they make their cuts and music is dubbed in later. That’s why so many dance scenes come off as awkward: The actors are just doing the zombie shuffle, moving to no background noise at all. In our movie, though, the plan was for them to dance to the actual song, which Dean and I thought would provide an excellent visual. At first, I was going to cut a demo on the road using my touring band, but my injury put the kibosh on that, so Dean asked me what song he should use instead. Luckily, I had the perfect track: My tempo model was Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode,” and that’s what they used on set.

“Footloose” laid over it perfectly in post. (Actually, it wasn’t as easy as I’d initially thought. “Johnny B. Goode” came out in 1958, before the use of click tracks. That meant that drummer Fred Below’s sound, while classic, was not quite precise enough for our purposes. We needed every note exactly on the beat for us to match it up, which in the days before digital manipulation meant the film’s music editors opened and closed the tape of the song by cutting pieces out or taping pieces in to ensure the beats were absolutely metronomic. It was painstaking and totally worthwhile.)

The last piece of the puzzle was put into place at my house in Sherman Oaks. Dean came over one rainy night shortly after I returned from Asia to nail down the bridge, which was the only part left. He arrived in the late afternoon, just in time for me to help feed the kids, and then hung out with Eva in the kitchen while I put them into the tub. Next, of course, was bedtime, so Dean waited around some more until they were asleep. Ordinarily, that would have been the time to get to work, but that night happened to be the final episode of M*A*S*H, which we ended up watching. Dean told me later he’d been nervous on the drive over about my reaction to the array of ideas he brought, but by the time we finally got down to writing, his anxiety had completely disappeared.

With the kids asleep nearby, we couldn’t work in the living room, so I took Dean to my laundry room. I sat on the dryer with a guitar on my lap, and he pulled out his notebook. Outside, it started to storm. I mean, the sky just opened up. It was like all of nature was conspiring to make this an epic evening. That laundry room was where we wrote the “First, we got to turn you around” part and the “Ah, ah, ah, tonight I gotta cut loose, footloose” transition back to the chorus. Dean scribbled down the new lyrics on a printout of the ones we’d already written, turned on his tape recorder, and I sang the whole thing. With that, the writing was done.

We had some time before filming, so on my ensuing North American tour, I worked out specific beats with my band during sound checks, which I viewed as de facto rehearsals. The opening guitar line is very much a twangy Duane Eddy influence. At first, I had my stage guitarist, Buzzy Feiten, try it, but he couldn’t get the phrasing I was after, so I ended up playing it myself. An avowed studio nerd, I went in the opposite direction for this one, grabbing my stage Stratocaster, plugging it into my stage amp, and cranking it up enough for a little raunch. It was exactly the sound I wanted. It came naturally, given that the style I was after was inspired by two of the first songs I ever learned to play: Eddy’s “Rebel Rouser” and the aforementioned “Johnny B. Goode.” To me, the opening lick to “Footloose” sounds incredibly familiar, even on first listen, like a classic rocker you can’t quite recall.

Nathan East came up with the bass line within one or two takes, and it really brings the chorus home. As opposed to “Devil With a Blue Dress,” in which the bass plays the root note over and over, Nathan played a Little Richard–style bass line, like “Good Golly Miss Molly” on steroids. The thing is, every chorus in the song is different because he was free-forming it off the top of his head, hauling ass at a hundred miles per hour. It quickly became clear that Nathan’s bass line was the heart of the chorus, so I doubled it on guitar. That drove Buzzy crazy when we played it live, because every chorus features slightly different bass and he had to learn each one of them. Why not simplify it and just pick the best one to repeat over and over? No way! That was the bass line. It had to be the bass line. That’s Nathan’s soul out there.

The groove of the song was inspired by David Bowie’s “Modern Love,” which was my favorite song to dance to that year. I slowed it down a little so my lyrics would sit on it better. It was a basic, gut-level, rock-and-roll drum groove, which was exactly what I wanted.

Wow. Putting it all on paper shows just how many influences can go into a piece of music. Bowie, Mitch Ryder, Duane Eddy, Paul Simon, Chuck Berry, Little Richard — all in that one song. Those influences were part of my DNA, the rock of my youth, and it makes sense that they’d show up all at once. That’s the history of rock and roll: a constant gumbo in the making, alive and cooking.

Cutting “Footloose” was simultaneously easy and complicated. Because it was my road band in the studio, and because we had already run through the song so much, those guys knew every note inside and out. They nailed it in two takes — the first one to get the sound levels right, and the second one was it. (Years later, my drummer, Tris Imboden, told me that as he was walking out of the studio with Nathan East, he said, “Whew — that’s the last time we’ll ever have to hear that.” Little did he know.)

Polishing the song was a bit more complex. For overdubs, I brought in percussionist Paulinho da Costa as well as a couple of synth players and two background singers. Even Tris, who’d initially played acoustic drums, came back and added that big Simmons electronic-drum sound that’s become so familiar in the breakdown. We eventually got up to 96 tracks, including guitar solos, handclaps, drum variations, and assorted instruments. That’s a lot for any song at that time, let alone a simple rock-and-roller. It’s especially crazy considering that, in the age before digital recording, we had to link four 24-track tape decks together to get what we wanted. It was worth it. After the song came out, I was at a party with some of the Fleetwood Mac folks, and Lindsey Buckingham pulled me aside. “How the fuck did you get all that information onto that record?” he asked. I used a gigantic hamburger press.

Prior to hitting No. 1, “Footloose” was the beneficiary of a perfect marketing plan. The single was sent to radio stations six weeks before the movie opened, and, man, did that make an impact. Footloose the movie topped the box office for the first three weeks of its release. “Footloose” the song was an immediate hit on MTV, spent three weeks at No. 1, and reached the top ten in seven countries besides the United States, hitting No. 1 in three of them. To this day, it’s the most fun song in my show, the one guaranteed to make an audience get up and dance. It’s almost Pavlovian: Even folks in tuxedos and formal dresses at fancy benefit galas boogie to that one. They’ve been trained by the movie. They’re not allowed to not dance. It’s simply un-American.

I actually pitched Dean the idea of my doing every song on the record, but he explained that with so much ambient music in the film — songs coming out of car radios and jukeboxes and the like — having one voice for all of it would ring false. We decided I’d do only two songs, the other one being “I’m Free (Heaven Helps the Man),” which Dean assigned me once I returned from my Asia tour. Actually, he didn’t even wait that long. I had a gig in Hawaii on the way home, and when I checked into my hotel, I found a faxed copy of his lyrics slipped under my door, waiting for me to write the music. A 19-year-old Richard Marx sang backup on the demo.

That one reached No. 22. Not bad for one album’s work.

Excerpted from Still Alright: A Memoir, by Kenny Loggins with Jason Turbow. Copyright © 2022. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc. Reprinted by permission.

Things you buy through our links may earn us a commission.