Contrary to an increasingly popular belief, Black horror didn’t begin when Jordan Peele released his masterpiece, Get Out. Nor has the genre subsisted solely on the critical and box-office success of his second film, Us, and his newest scare, Nope. While it’s fair to say Peele brought Black horror to the “mainstream” (a loaded term often defined by white tastes), cinema history holds plenty of thrilling movies directed by and starring Black folks. These films avoid the present-day expectations of Black cinema, a category made thornier yet flatter in its definition over the past decade. They evade the demand to render race as quantifiable, singular, or monolithic and resist the pressure for Black art to reductively explain Blackness itself. Here are Black horror films that express the larger range and broader facets of Black storytelling and existence.

Beloved (1998)

The only Toni Morrison novel adapted for the screen, director Jonathan Demme’s Beloved is the movie every psychological slave horror film that came after has failed to match. It follows Sethe (Oprah Winfrey), a former slave and mother of three living in Ohio who has a poltergeist in her house. An old friend from Sweet Farm Plantation, Paul D (Danny Glover), appears at her doorstep, as does the reincarnated version of her murdered daughter, Beloved, played by Thandiwe Newton in a multifaceted performance that evades dramatic definition. The trio forms a tenuous triangle of Black folks debilitated by the pain they still feel from slavery. Beloved becomes an albatross around Sethe’s neck as she tries to atone for the lost years. Demme’s adaptation succeeds in part because Morrison doesn’t ground the horror in the physical destruction of Black bodies. Instead, the frights come from the emotional voids caused by the ways slavery permanently altered African American families, leaving the survivors to digest their own tortured memories.

Black Box (2020)

A kind, pure, fatherly love lies beneath the psychological terrors of Black Box. It’s an affection nurtured by two broken minds. The second entry in the “Welcome to the Blumhouse” series, this film, written and directed by Emmanuel Osei-Kuffour Jr., walks with a familiar Black Mirror stride. After surviving a car crash that kills his wife, photographer Nolan Wright (Mamoudou Athie) struggles to care for his precious daughter, Ava (Amanda Christine), amid his bouts of amnesia. Worried that he’ll lose Ava to child protective services because of his condition, he enrolls in an experimental cognitive-research study headed by Dr. Lillian Brooks (Phylicia Rashad), wherein he dons a VR headset to access his buried memories in a sunken place. Black Box would easily slip into Get Out pastiche if Osei-Kuffour hadn’t taken an ingenious approach. Without spoiling too much, Nolan eventually discovers he has another consciousness, who was once a father too, living in his brain. But this father isn’t the gentleman Nolan is: The irate specter pines for another chance to right past wrongs. The fight for control of Nolan’s body, in which the boundary between nightmare and memory dissolves, awakens a surprising wellspring of tenderness.

Bones (2001)

You’re probably not going to find a more stomach-churning movie than Ernest Dickerson’s grisly blaxploitation homage Bones. Snoop Dogg stars as the titular Jimmy Bones, a numbers runner murdered and buried in his own brownstone by a crooked cop (Michael T. Weiss) and a drug dealer (Ricky Harris). Twenty-two years later, four teens buy the place in hopes of converting it into a nightclub. They discover a dog, in which Bones’s spirit resides; the more they feed it, the closer the vengeful Bones comes to resurrection. The legendary Pam Grier totally commits as a moaning neighborhood psychic, Bones’s former lover. Dickerson’s grim film emphasizes the importance of leaders in Black communities by pitching Bones as a calming influence while showing the nefarious ways white folks have undermined the neighborhood anchors. Nevertheless, the brain-searing images are what jut forward: A scene involving maggots shooting out of a dog’s mouth will have you skipping dinner for the next several nights.

Bugged (1997)

With the advent of serious-minded Black horror — propelled by expectations for conversations about racism and structural inequities — a misconception has arisen that such films cannot be silly. Ronald K. Armstrong’s low-budget Troma film Bugged dispels this myth by melding Ghostbusters with Ants for a rubber-bug movie about two bungling exterminators who accidentally spray cockroaches with a mutative chemical. The roaches not only grow to the size of dogs, they acquire superintelligence. At one point, they use a raw whole chicken tied to a string as bait for the exterminators. In another instance, a roach fires a gun. Bugged isn’t out to impart some deeper lesson. It instead takes well-earned glee in simply being a ludicrous and fun throwback B-movie.

Def by Temptation (1990)

If you refashioned Bill Duke’s A Rage in Harlem and Emerald Fennell’s Promising Young Woman into a single horror film, you’d get close to writer-director James Bond III’s sexually promiscuous Def by Temptation. In it, a succubus named Temptation (Cynthia Bond) pursues Joel (Bond III), a sheltered 21-year-old from the country who’s studying for the ministry, in hopes of corrupting him. This Troma production could easily have been a cautionary, woman-hating tale, but the smart script envelops the real terrors of the 1990s — such as the AIDS epidemic and the fallout from Reaganomics — for unquestionable frights. Temptation often cruises bars for unfaithful men, luring them back to her place with the promise of erotic thrills. DP Ernest Dickerson sets up oblique compositions, soaking Temptation’s bloodbaths in deliciously sinister lighting: The most gruesome scene involves a bar full of zombie men, scarred, oozing pus, and vomiting up the sins of their infidelities, pursuing Joel’s worried friends K (Kadeem Hardison) and Dougy (Bill Nunn) in an inventive, intelligent interrogation of 1990s theories on gender and sexuality.

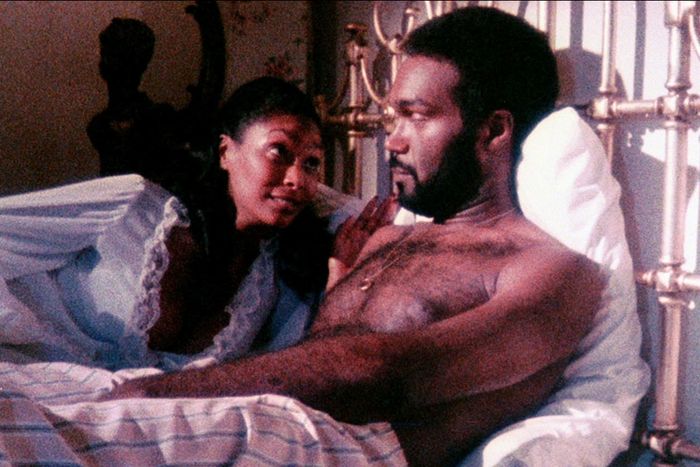

Ganja & Hess (1973)

Back in the 1970s, blaxploitation films provided African American directors the opportunity to interpret popular horror creatures like vampires and zombies through a Black lens. While most aimed for campiness, writer-director Bill Gunn’s sensual, rapturous masterpiece Ganja & Hess stands above the rest. Duane Jones (Losing Ground, Night of the Living Dead) stars as Dr. Hess, an anthropologist who becomes a vampire after his assistant, George Meda (Gunn), stabs him with an ancient dagger. Meda’s wife, Ganja (Marlene Clark), and Hess fall in love and together mix vampirism with sex. Ganga & Hess is an exacting, unforgettable portrait of lustiness — sticky blood glistens on Black bodies — and religion. A climactic church scene, in which Jones completely gives himself over to spiritual ecstasy, remains with you long after the screen fades to black.

Kindred (2020)

With the dissolution of Roe v. Wade by the Supreme Court, British writer-director Joe Marcantonio’s Kindred — a smart, precisely rendered physiological horror about the ways motherhood and madness intertwine — feels all the more important. Charlotte Wilde (Tamara Lawrance) and her boyfriend, Ben (Edward Holcroft), are planning a move to Australia, much to the chagrin of Ben’s controlling and wealthy mother, Margaret (Fiona Shaw). Their future is disrupted, first when Charlotte becomes pregnant and then when Ben dies in a freak accident. His mother and seemingly nice stepbrother (Jack Lowden) house Charlotte at their stuffy country estate. It doesn’t take long, however, before she realizes that their kindness hides insidious intentions. Marcantonio and Jason McColgan’s script doesn’t didactically spell out its themes: mental health, gaslighting, racism, the ways the medical system can undermine a woman’s choice and her bodily autonomy. It’s too intelligent a movie for such easy swings. Instead, the film uses confined framing and compositions to express how with each passing minute, Charlotte is further dehumanized to the point of merely acting as a vessel for the demented aims of a white family. Its chilling ending, bathed in loss and imprisonment, is the kind of recurring nightmare that grows scarier with each watch.

The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988)

For decades, when Hollywood ventured either to Africa or the Black Caribbean, it did so through leering, exploitative white eyes. In the process, the cultures of these regions were leveraged mostly for shock rather than understanding. Wes Craven’s The Serpent and the Rainbow, though told from a white perspective, manages to avoid such pitfalls. Anthropologist Dr. Dennis Alan (Bill Pullman) finds himself embroiled in larger religious issues when he ventures to a politically unstable Haiti that’s on the verge of overthrowing President Jean-Claude Duvalier. Alan is there to learn about a magic white powder used in voodoo rituals that has the power to render its user so still they appear to be dead; he believes such a drug could revolutionize medicine. Craven, for his part, luckily doesn’t depict voodoo as a spooky entity. Instead, he takes care to explicate the actual religious and social power it holds in Haiti. The mostly Black cast (Paul Winfield, Brent Jennings, Cathy Tyson, and the villainous Zakes Mokae) are more than peripheral elements. They bring a verve and a reality that steer The Serpent and the Rainbow away from appropriation into a fully felt zombie-voodoo flick.

Sweetheart (2019)

A mysterious creature feature, J.D. Dillard’s Sweetheart recalibrates the horror-fable subgenre into a character study. The heroine, Jenn (Kiersey Clemons), washes ashore on a deserted island after her boat sinks. When she wakes up, she discovers the dead body of her best friend, along with an endless black hole at the bottom of the seabed and a deadly humanoid fishman lurking in the darkness. Although her boyfriend and another peer turn up on the island, they offer very little solace: They don’t believe her story about the monster. Clemons sketches a rich inner life for Jenn, a character with few lines of dialogue, as she learns the kind of self-sufficiency required to survive with few supplies and even fewer weapons. Sweetheart excels at delivering unnerving scares while Jenn works to outwit her predator. Even when inserting the other survivors, Dillard doesn’t totally slip into the tired trope of humans being the real brutes. He understands that what’s scariest is what hides in the shadows.

Tales From the Crypt: Demon Knight (1995)

Not until Ernest Dickerson’s name appeared in the opening credits of Tales From the Crypt: Demon Knight (a spinoff of the popular horror-comedy television series) did I totally register the force he provided to Black horror in the 1990s. His third appearance on this list (after Bones and Def by Temptation) is a wild and careening demonic tale about a guardian (William Sadler) toting the blood of Christ to an ancient church turned hotel in the middle of nowhere New Mexico. Billy Zane, in possibly his most gonzo role, plays the demon known as the Collector, who’s pursuing the relic. Gory kills and horny scenes abound in a grandiose film supported by a deep ensemble that includes Thomas Haden Church, Dick Miller, and the ever-captivating CCH Pounder. But it’s the way Dickerson nimbly pulls focus from the typical white hero to Jada Pinkett Smith’s Jeryline, a determined convict on work release, that sticks with you most. She upends horror expectations by rising from the narrative wings to the heroic rafters.

Tales From the Hood (1995)

Tales From the Hood, the Spike Lee–produced horror anthology from writer-director Rusty Cundieff, begins and ends with street justice. Three gangsters arrive at a mortuary owned by the eccentric and frenzied Mr. Simms (Clarence Williams III) to purchase some drugs. As this film’s wisecracking Cryptkeeper, Simms tells the trio four stories about the dead men who occupy the funeral home’s several caskets. In these tales, a Black cop is haunted by the ghost of a Black reformist who was viciously murdered by his white colleagues; a battered Black kid imagines his abusive stepfather as a gnarly green monster; small Black dolls governed by the spirits of the enslaved take revenge against a KKK southern senator occupying their former plantation house; and a cold-blooded gangster is sent to a reformist prison where he’s forced to confront his victims. The major themes coursing through Tales From the Hood — police brutality and Black-on-Black crime — were of the moment and unflinching in their politics: Black folks in league with the police and dirty white politicians get brutally punished here. And the kills — men squashed like Play-Doh, stop-motion monsters, and syringes deployed like missiles — remain nightmare inducing.