The sound of drill is the brazen brrrrrap of street-level rap over the past decade. It’s the unsettling, aestheticized sound of gunplay evoked by spraying hi-hats, double-tapped rhyme blasts, and a bottomless pool of ad-libbed variations on BANG! BAM! POW! Hyperlocal yet deeply translocal, it’s the sound of New York via Chicago and London. It’s the self-made soundtrack of young Black artists in these cities as well as a rhythm that any laptop producer can program after a YouTube tutorial. Drill can be many things, but as a musical term, it increasingly refers to a distinctive pattern, one that bears audible witness to its locale-hopping history.

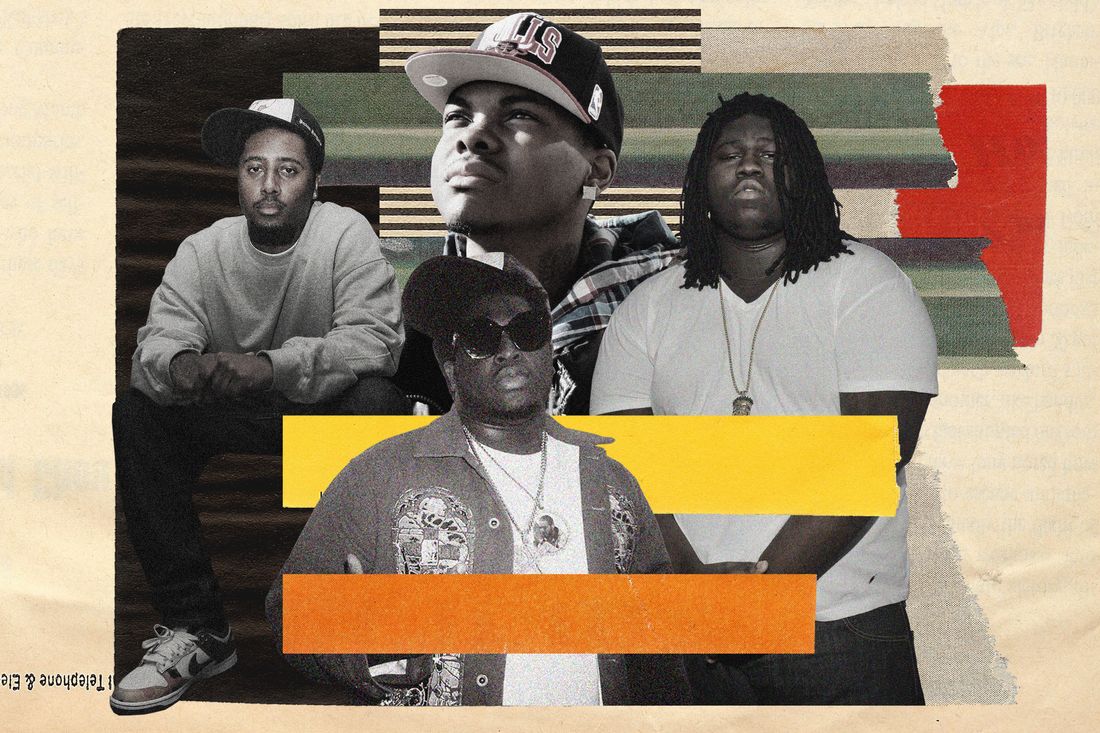

New York drill, as told by …

The Chicago Sound

Chicago is where the term drill took on new meaning, first as slang for shooting and killing and then, with Pac Man’s “It’s a Drill” in 2010, for music about witnessing both. The branding stuck not just because the songs and raw videos of Chicago’s Chief Keef, G Herbo, Lil Durk, and Lil Reese centered such themes with captivating power, but because these productions musically embodied the dreadful ambience of a city dominated by gun violence. Surgically slow tempos of 65 to 70 beats per minute allowed an unhurried delivery of speech-rhythm threats over booming bass with synthetic snares, snaps, or claps anchoring the backbeat. The heavy, almost martial drums — Chicago producer DJ L cites marching-band cadences as a cornerstone in his snare patterns — moved in lockstep alongside foreboding melodic loops indexing horror films (eerie one-finger piano lines) and big-boss battles (church bells and crashing cymbals).

As the sound of Chicago drill crested from 2011 to 2013, it owed a large debt to Atlanta, especially the muscular pomp of second-wave trap, popularized in 2010 by producer Lex Luger with Waka Flocka Flame. Influential Chicago producers like Young Chop took strong sonic cues from Luger and other trap beat-makers. Many of drill’s biggest productions at the time were nearly indistinguishable from the bounce of trap, but they shifted the mood and attitude. As they tended toward slower tempos, more space started to creep in: room for ad-libs, for tension to build, for cavernous pauses between bass kicks and long stretches with no drums at all. But while its sound offered an alluring template, Chicago’s unhurried approach could feel plodding, airless.

The London Sound

This is the quality that changed most clearly once drill had become the sound of rap in London by the mid-2010s. In the hands of young Black British producers smitten by Chicago drill but raised on a diet of grime, dubstep, and other dance music, drill’s open space offered room for other rhythms to hop aboard. Appearing within a year of Chicago drill’s explosion, early U.K. drill tracks by Stickz or GR1ZZY & M Dargg emulated Chicago’s, save for the accents. Yet in just a couple of years, the beat shifted, inflected by the U.K.’s distinctive Afro-diasporic heritage. On many tracks, like 2014’s “No Rules,” by Section Boyz, the snare on the fourth beat recedes as other percussive filigree fills in. By 2016, the same beat was replaced by bubbling soca-style snares traveling twice as fast, as in 67’s “Lets Lurk.”

London producers sutured early drill’s half-step stomp to grime music’s angular, up-tempo grooves and timeless Afro-Caribbean polyrhythms. For timbres and arrangements, they likewise drew from a local palette: sinewy bass lines surreally sliding from one note to the next, cherished percussion bits sampled from such iconic grime instrumentals as Wiley’s “Ice Rink,” and snarling synth smears recalling dubstep’s half-time wobble. With this infusion of energy and style, something subtle but crucial happened to drill’s formerly plodding beat: It began to float. While the first snare of the backbeat (on the second beat) remained prominent, a clear nod to Chicago and Atlanta, the second frequently failed to appear at all, or struck a beat later than expected. The effect was as if each bar contained a half-measure of Chicago “half-time” (at, say, 70 bpm), followed by a full measure of London “double-time” (140 bpm): ONE-and-TWO-and-1-2-3-4. In contrast to the typical trap/Chicago drill beat, the hi-hats have moved from on-beat and triplet subdivisions to a steady 3+3+2 polyrhythm, that mainstay of Afro-diasporic music from dancehall to salsa — what some would call tresillo, or what reggaeton devotees know as dembow.

The New York Sound

The same Afro-diasporic rhythms have been hot in New York since the heyday of the Charleston a century ago, especially during the past two decades of dancehall crossover. This context primed another serendipitous moment of Black Atlantic exchange in the case of drill in 2016, abetted by the internet. The children of the children of Caribbean immigrants in London started making “drill-type beats” for their counterparts in Brooklyn (many of whom also come from Caribbean families). They engaged YouTube’s recommendation algorithms to direct their work to established and aspiring New York drill artists: 22Gz, Sheff G, Pop Smoke. These Brooklynites, inspired by what they heard from Chicago but seeking a sound of their own, decided the tailor-made beats hit the spot, not always knowing where they had been produced.

These beats propelled NYC drill’s big hits and helped it come into its own. Modeled on the sound of U.K. producers such as AXL Beats and 808Melo, the icy but dancy approach gave Brooklyn drill its own energy and a sound distinct from Chicago’s. Producers in the Bronx and other boroughs picked up the baton and started adding sample-based touches to the template, heard on songs like B-Lovee’s Mary J. Blige–indebted “My Everything,” bringing drill into more direct dialogue with all manner of pop. Drake has already come knocking for beats, while posthumous Pop Smoke songs and new Fivio Foreign tracks climb the charts. This evolution away from macabre, macho music might have appeared incongruous at first, but it now seems fitting that the first major star to emerge from drill’s biggest new scene broke out with a song called “Welcome to the Party.”

.

Listen to a (brief) evolution of the sound of drill

More on drill music

- Everything We Know About Sheff G and Sleepy Hallow’s Indictment

- A$AP Rocky Takes ‘Full Responsibility’ for Short Rolling Loud Set

- The Voice of New York Is Drill

- The Drill Songs to Know