There was a three-year period in the ’90s where Coolio — the bug-eyed Compton-bred rapper best known for sampling a Midwest funk band to breakthrough success — became such an omnipresent figure in pop culture he had the power to help turn a film floundering in review hell into one of the top movies of the year.

“The test screenings of it were not going well,” he said of Dangerous Minds, the 1995 drama starring Michelle Pfeiffer, which featured Coolio’s soon-to-be-signature song, “Gangsta’s Paradise.” “They were afraid that the movie was going to flop; they were terrified.”

Indeed, the latest in a wave of ‘80s and ‘90s coming-of-age movies about a hard-nosed adult nurturing inner-city youths was on the verge of being a commercial bomb. It was also rife with stereotypes and, according to Roger Ebert, watered down to comfort white audiences through Bob Dylan lyrics instead of the rap music the book it’s based on mentioned. Luckily, the film also had a secret weapon: Coolio’s lead single from the soundtrack, which dropped 10 days before the premiere. Powered by a rich baritone twisting Psalm 23 into his own, singer Larry “L.V.” Sanders’ haunting yet gospel-tinged chorus, and a gloomy music video, the song would help propel Minds to No. 1 opening weekend. A month later, the soundtrack and single both hit No. 1 on the Billboard charts, barely a week apart. (The movie eventually made over $179 million at the box office.)

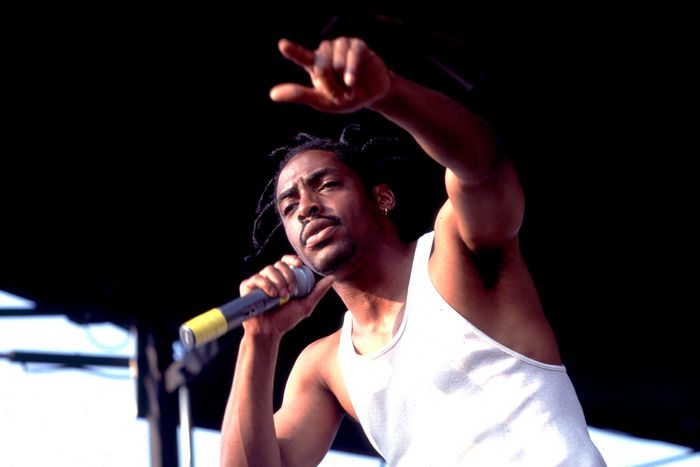

For Coolio, who died Wednesday at the age of 59, “Gangsta’s Paradise” was the moment he became one of the biggest rappers in the world. Armed with a striking coif of braids and a gruff yet honest West Coast demeanor, the man born Artis Leon Ivey Jr. had managed to achieve global fame without turning his back on his Compton roots.

“I think he was the reason our film saw so much success,” Pfeiffer wrote in her tribute. “I remember him being nothing but gracious. Thirty years later I still get chills when I hear the song.”

Built off a riff of Stevie Wonder’s “Pastime Paradise,” “Gangsta’s Paradise” was a detour from the party raps Coolio had already become known for. It was dark and ethereal, a song befitting a funeral rather than a white savior film (though the track still needed Wonder’s blessing and the promise of no profanity on it to get the original sample cleared). It later won a Grammy for Best Rap Solo Performance in 1996 — though narrowly losing Record of the Year to another single boosted by a soundtrack (Seal’s “Kiss From A Rose”) — while solidifying Coolio’s work as an already in-demand superstar. It was an impressive rise for a man who had battled asthma throughout his life, joined the Baby Crips as a teen to fit in, and once held odd jobs — as a firefighter battling blazes in the northern California forests and as a security guard at Los Angeles International Airport — to make ends meet.

His early days in hip-hop found him cutting his teeth in the Los Angeles indie circuit alongside another gruff firebrand, WC. Together, the two were part of the Maad Circle alongside DJ Crazy Toones and Big Gee, releasing their debut album Ain’t a Damn Thang Changed in September 1991. On songs like “Behind Closed Doors” and “You Don’t Work, U Don’t Eat,” Coolio gave a direct, honest depiction of life in Los Angeles, whether for former felons running afoul of the LAPD or for men deciding to finally opt for a life of crime because a normal 9-to-5 feels bleaker. “Money ain’t everything but neither is brokeness,” he bluntly raps on “You Don’t Work.” “Give me a knife ’cause I can’t live off happiness.”

Once WC linked up with another West Coast supergroup, Westside Connection with Ice Cube and Mack 10, Coolio went solo. His 1994 debut album It Takes a Thief blended sliding, sample-heavy production with lyricism pointing out flaws in the government, the paranoia of gang banging, poverty, and more. On “County Line,” he riffed over a tweak of Zapp’s “More Bounce to the Ounce” and the Bar-Kays’ “Hit and Run” about a day where he scammed the government for welfare assistance: He questions everyone in line looking at him like an alien despite having a music career and admits to a social worker about a prior crack cocaine addiction. “Took one hit of the crack and was hooked,” he raps. “She sittin’ there wondering when I’ll get to the point.”

It Takes a Thief led Coolio to early fame. The album went platinum mainly off the back of single “Fantastic Voyage.” A souped-up version of Lakeside’s 1981 hit of the same name, the song was about the rapper looking to have a simple day void of gang politics and bullshit, one where he can eat steak with beans and rice. By marrying similar subject matter and funk vibes as Snoop Dogg’s “Gin and Juice” and Ice Cube’s “It Was a Good Day,” it eventually hit No. 3 on the Hot 100. The single, along with Coolio’s distinct look, name, and laid-back demeanor, gave white audiences a new rapper to root for. Even when things had the opportunity to go south, he was able to charm detractors. Weeks after he won his Grammy, he appeared on The Late Late Show With Tom Snyder. After recalling his childhood growing up in Compton, a suburban mom called the show congratulating him on the award win. However, she was saddened her 10-year-old son heard cursing on his album Gangsta’s Paradise. But Coolio quickly calmed her nerves. “If you let your son watch Rap City sometimes or let him watch MTV in the daytime, I do a lot of things with both BET and MTV,” he told her in a warm, disarming tone. “Oh, and Nickelodeon!”

But in Coolio’s eyes, that brief ’90s run and the success of “Gangsta’s Paradise” would ultimately become a curse. In a 2015 interview with Sway of Sway in the Morning, he felt the song “overshadowed” his other work. Two years after it became a pop hit, others were using the formula laid by him and producer Doug Rasheed, tweaking it to their own style. “C U When U Get There,” the lead single from Coolio’s 1997 album My Soul, attempted to repeat the accomplishments of “Gangsta’s Paradise,” with a story about a fallen friend. It found modest success, but nowhere near its predecessor. And while My Soul eventually reached platinum status, it failed to hit the highs of its double-platinum-selling predecessor, leading his label Tommy Boy to drop him. By 1997, Diddy’s East Coast empire Bad Boy had reached its zenith, matching a mix of sadness, glossy wealth, and New York demeanor with beloved pop-music samples. It seemed like mainstream America no longer had a space for Coolio, a chameleonic superstar who could lay verses alongside the Notorious B.I.G. about the early days of Oakland’s Black Panther movement for 1995’s Panther soundtrack; trade bars with B-Real, Method Man, LL Cool J, and Busta Rhymes for Space Jam, the beloved 1996 Looney Tunes basketball movie starring Michael Jordan; and record the theme song to the Nickelodeon sitcom Kenan & Kel, all without feeling gimmicky. For a brief moment in time, Coolio could be anything to anyone.