Nineteen ninety-seven was a pivotal year for U.K. guitar rock. Be Here Now drove Britpop off a cliff as Blur, Urban Hymns, and When I Was Born for the 7th Time salvaged it for the future — all while OK Computer and Ladies and Gentlemen We Are Floating in Space sat in the corner and soundtracked the world’s most transcendent shrug. But the LP that’s aged the best is the debut from a mostly instrumental Glasgow post-punk band (well, they would have preferred post-goth) named after the devious little monsters in Gremlins. In an era when rock music was defined by loud proclamations, Mogwai’s Mogwai Young Team turned silence into a sledgehammer. This simmering chaos validated every Joy Division and Slint fan in that it was still possible to surprise and unsettle disciples of the increasingly safe-sounding punk canon; it also inspired Stephen Malkmus to call Mogwai “the band of the 21st century.”

Mogwai has spent the intervening decades putting on grand live shows and releasing increasingly lush and cinematic records that feel like the spiritual fathers to today’s post-punk and emo scenes. A group notorious for its dark humor and picking fights in the press (most famously with Blur) has transformed into a living example of how to age gracefully as a dependable independent band. Their emphasis on atmosphere and dramatic sonic shifts over catchy choruses is their blessing and curse: Only Mogwai can pull off Mogwai. Although most of their albums have charted respectably throughout Europe — at least compared with their more marketable Brit rock brethren — they finally found true commercial success in 2021. Last year’s As the Love Continues surprised everyone, including the band, by earning Mogwai their first U.K. No. 1 LP thanks in large part to a fan-driven social-media push. As if on cue, we now have a memoir to catch everyone up on the story of Mogwai. Sort of.

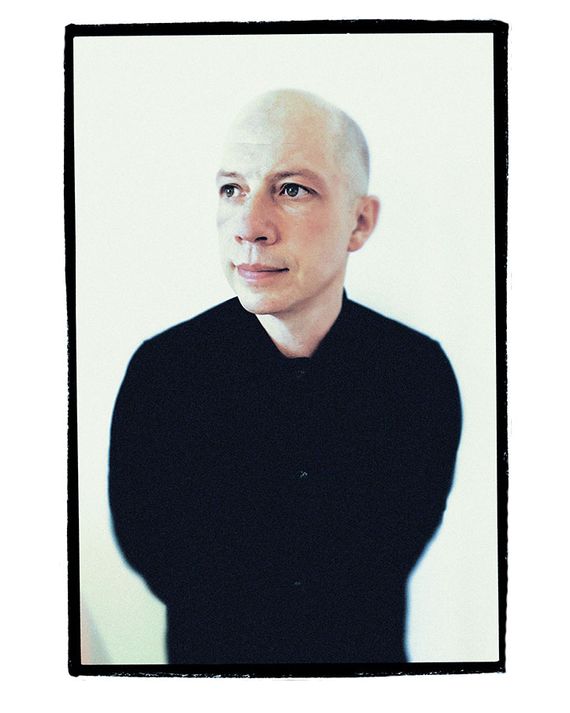

In Spaceships Over Glasgow: Mogwai, Mayhem and Misspent Youth (out September 29), Stuart Braithwaite, the band’s co-founder, guitarist, and as-needed vocalist, retells Mogwai’s history through a unique lens: The memoir is bookended by stories of Braithwaite’s late father, Scotland’s last telescope-maker, who passed down a love of seeking the ethereal of the night (and once turned down Reagan’s offer to work on the “Star Wars” defense program). Mogwai fans will love the behind-the-scenes band details, but this is Braithwaite’s story with all its highs and lows; there’s plenty of mayhem and misspent youth that Braithwaite doesn’t shy away from in his straightforward prose.

“With music, it’s something I’ve been doing since I was a kid,” says Braithwaite over the phone while driving around the Scottish Highlands, north of his home base in Glasgow. “Whereas this is something I’ve been doing for the last year and a half. It’s just me. I don’t have my bandmates to be there and help. Well, actually, to be honest, in some cases, they kind of did help me write the book. But it’s my name that’s on the front!” Braithwaite is as funny and self-aware in conversation as you’d hope, talking with the hard-earned wisdom of someone who can laugh at the many mistakes of his youth.

When did you realize you were going to write a memoir?

It was just towards the end of the lockdown but before live concerts had started back. I’d been reading a lot. I just got reading glasses for the first time in my life. I was wondering what I was going to do because we’d made an album, but there was no sign of us going out on tour anytime soon. I remember that Lee Brackstone at White Rabbit, when I was doing a Q&A for the release of a book about John Peel called Good Night and Good Riddance, asked me in the pub after if I ever fancied writing a book. Knowing I had all this free time, and I had been doing a lot of reading, I just emailed Lee, and then he was like Okay, send me a chapter.

You got reading glasses? Very post-punk.

[Laughs] Yeah.

The memoir’s title is interesting. In the past, I’d describe your music within the context of post-punk and shoegaze. Reading more about your father and your upbringing, maybe stargaze is a better word to describe Mogwai.

I like that. I’m not huge on labels, but I always kind of liked sci-fi. That sense of wonder is something I hope comes through in our music.

The memoir covers every Mogwai album but goes in depth on just the first two records. My favorite Mogwai record is Hardcore Will Never Die, But You Will, and I think it got two paragraphs.

Because everything’s new. The first time you go into a studio to make a record — I mean, other than being at a music college, I’d never really been in a studio. We’d never even really thought about making an album, and I think that comes across in the book because we kind of lost the plot a little. The stress drove us all a bit nuts. That kind of intensity and borderline psychosis pushed us to make something that, in retrospect, was special, especially considering how young we were. For a long time, I was disappointed with Young Team. But now I’m like, Oh my God, how did a bunch of kids who were mostly drunk make that music? I just thought that period had the best stories. I think as you grew up, you learned to navigate life a lot better. Everything’s a little bit easier. But there’s not as much chaos, which probably means fewer interesting stories.

Hardcore Will Never Die, But You Will is one of my favorite records too. The actual recording of it was pretty painless. We were pretty together by that point. I can’t think of too much that would be worth writing about other than some stuff that I probably mentioned, like the title of the album is a funny story or that it was the first one we put out on our label. But we’re not like shaving our heads or turning into pacifists, Manson-family kind of vibe or whatever.

Do you find that at all — I don’t know if frustrating is the right word, but when there is so much chaos that can result in great music and that chaos is what attracts people in the first place?

I don’t know. I also think that as you get more experienced and you look at what you’ve done, you can realize how you made things without the kind of — I don’t know — collateral, personal damage to your lifestyle. If we were trying to live in our 40s like we were in our late teens or early 20s, it just wouldn’t work.

I ask because it felt like the initial appeal of Mogwai was the chaos, especially how anti-Britpop it felt. Britpop thrived on such grandiose proclamations, especially in the lyrics, and then here comes this mostly instrumental band that talks a lot of shit in the press. Liking Mogwai wasn’t only musically satisfying but felt like a stance on something.

Most people in their 20s may not quite understand that culture was very different back then. Everything wasn’t available. We had to make a lot of noise — well, both figuratively and actually make a lot of noise — to prove that what you were doing was important. We felt that what we were doing was very important and, conversely, what was happening in the mainstream was very flattened. We were inspired by Joy Division, Sonic Youth, My Bloody Valentine, and music that has real weight to it, whereas everything else seemed dumbed down. People were pretending to be stupider than they were. The kind of music that we were inspired by was a real afterthought then. So we wanted to share a little bit about it.

Some of it just seems weird now because it would never happen. In a world where you can say anything to anyone and they will actually hear it, the whole concept of a band needing to wait to be interviewed to let the world know what they think just seems twee. The way music is released and consumed today, it couldn’t be more different. It feels like someone’s describing those player pianos where you put the paper in and they play the music for you. It feels so antiquated that you had to either hear a song on the radio or buy a record; otherwise, you couldn’t hear it. That just seems really from another century — I mean it was from another century — but it feels like it’s from 100 years ago, not 25.

With all that said, I did want to read back this quote of yours from your first cover story that you highlighted in your memoir: “Us being an instrumental band was as important as Bob Dylan confronting racism in the ’60s.”

It’s ridiculous. It’s one of the stupidest things I’ve ever said.

I know you and the rest of Mogwai have always had an ironic and dark sense of humor, especially when talking to the press. I’m reading this out of context, but still, even this wouldn’t fly today.

No! And it shouldn’t. That is a dumb thing to say and belittling of something really serious. I think I made the point in the book: I was kind of coerced into going down that line. But it still gives me a full-body cringe.

If someone wasn’t pressing you to say something outlandish at that moment, do you think you’d still say it to create that noise you talked about earlier?

I look back at some of the things I said, and they make me genuinely laugh where I can kinda see it. But I think, at that point, the guy who was interviewing me was probably just like, “You need to say something to make sure you get the cover,” and I was just like, Okay! When people do things kinda like that, I always think it seems ’90s because that was the dynamic of the time. I remember Nicky Wire from the Manic Street Preachers, who is genuinely one of the nicest people I’ve ever met, saying on stage at that he hoped Michael Stipe died of AIDS. I’m not a big fan of R.E.M., but, I mean, Jesus Christ.

I think a lot of that can be related to the fact that if you were uncool and roundabout then, you were invisible. Whereas I don’t think the concept of coolness and uncoolness even exists anymore. I think the internet has killed that. In many ways, that’s a really good thing. In some ways, not so much. But in most ways, I think it’s a good thing because I think it means that music exists on its own terms rather than everything being part of a sort of more collective sense of what is in and what is out, you know?

I’m reading Glamorama, by Bret Easton Ellis, right now, and it’s so of that time. I was thinking that someone maybe your age must read this and just think it’s insane. Whereas even though I’ve never been involved in fashion or anything like that, the way the main character thinks about the world and thinks about culture was kind of normal! Even though he’s going for a slightly American Psycho kind of fashion, it’s such a great document of what was a very odd time.

There is that lack of bite among young bands today, for better or worse. Anyone saying anything remotely bad about someone on Twitter feels like a huge story even if it’s minor stuff. Off-line, I hear among my colleagues a missing of that sense of fun and friendly competition in music.

I wish younger musicians would be more opinionated. I do think that there’s a blandness. I think a lot of newer artists look and sound quite like each other, and maybe that needs to be called out a little bit. But I think there are other elements to it. If you don’t like something now, you can just go and listen to something else. If you’re into harsh noise, you can find thousands of playlists playing harsh noise. Whereas when we first started — certainly, where we grew up — there were one or two radio stations and maybe one TV show that played music. Whatever was popular, you were bombarded with it with very few choices to hear anything else, whereas now the world is drowning in choice. If you aren’t a fan or it wasn’t what you wanted to listen to, you can just go listen to something else.

I talk about it in the book about how — to put it mildly — we weren’t fans of Blur. That probably seems kind of odd now. But you couldn’t escape that at the time. You heard it everywhere. It’s all people would talk about. To our way more left-field ears, it was an affront. In some ways, you did have to be there. Also we weren’t interested in pleasing anyone. We never really expected anyone to like our band in the first place. We weren’t worried about upsetting anyone because we didn’t give a fuck. We were already overachieving.

Are we ever gonna get a reprint of the “Blur: Are Shite” and the “Gorillaz: Even Worse” T-shirts?

We never actually made the Gorillaz one. That was just a joke. But probably not. I think that kind of stuff is funny when you’re 22. But then when you’re in your 40s, it seems slightly psychotic.

Have you ever talked to Damon about that?

I’ve only met him once, and it was at a charity thing. It didn’t come up. I don’t think he’d give two fucks.

I do think a reprint of the shirts would go well.

We could probably make a lot of money. It’d probably land differently in America too. I don’t think Blur was particularly well known in America. I don’t think they were playing much bigger shows than we were at that point. But whereas here, they were playing stadiums.

I reread the original 9.7 Pitchfork review of Mogwai Young Team and laughed at the line that described Mogwai as just emo kids obsessed with 2001.

The irony is that we weren’t even emo back then, but I like the fact that we fell into that bracket. I recently read the book Sellout. I loved the book, but I genuinely didn’t know any of the bands. Like, I didn’t know the music of any of the bands. I was checking them out as I was listening to the book, and I guess a lot of it was very, very of its time. But yeah, I was never really that into that world. Maybe goth was the original emo.

Could you articulate the key variable that determines what U.K. bands break in America?

Can you hold on for one second? [Stuart speaks to someone off the line.] Sorry, we’re dropping our dog off.

What’s your dog’s name?

He’s called Prince. He’s pretty famous on the Internet, if you want to check him out on Instagram. He’s called Prince of Glasgow. He’s a very handsome dog. My wife just said he’s more interesting than my book.

So yeah — I think we’ve always done fine in America. We’re maybe seen as more of an underground band than we are in Europe. But I’m not gonna complain. We turn up and play a show, and people come. I’m pretty grateful for that. I know a lot of bands who do well in Europe and struggle to play to many people at all in America. I’m grateful for the consistency.

Among your European peers, what bands would you shout out as doing well overseas that maybe in America, even with the internet, we aren’t as in tune with?

If I’m being totally honest, the bands I’m thinking about are bands that I don’t think are that good. I think that Americans are quite refined with music. There’s a really good culture of really curatorial record stores and college radio. The bands I was thinking of are more bands that are mainstream indie or almost radio-rock stuff. I guess to get that stuff to be popular in America costs a lot of money and radio plugging and endless touring.

There’s also this wave of new U.K. post-punk bands that have fans in America, like black midi, Squid, and Yard Act. I don’t think we have a defined phrase for it, but it feels like post-Brexit post-punk. I hear Mogwai’s influence on all these younger groups.

I’m super-excited about young people making weird music just from a general philosophical viewpoint. I’ve seen all those bands and really enjoyed the shows. I like the fact that black midi are big Slint fans, but they’re going at it from a fun, party kind of angle rather than an emo, supercilious point of view. I like the fact that they’re doing something different with the influence rather than just sounding the same, you know?

Last year, Mogwai got their first U.K. No. 1 record, and I remember watching it happen in real time on Twitter with fans retweeting the news of asking everyone to stream the new album at a specific time. And it worked.

That was one of the weirdest weeks of my life. It was my wife, Elisabeth, who noticed this other musician, this rapper Ghetts, was pushing hard on social media for his album. And she was like, “You need to do this!” And yeah, you know, we went for it. The feeling about it made me really grateful and quite humble as well. There’s so much negativity on social media — I think that it, by its nature, pushes people apart — so I think it was nice for it to have something that felt generally a kind of nice, positive thing. We’re an unlikely band to get a No. 1 record. It almost kind of fell in our lap. Seeing New Order and the Cure tweet about it was special.

It feels like a lot of artists’ campaigns on social media are mental gymnastics of wanting to come across as authentic while still being very planned out and market tested. Like Wendy’s tweeting “Yas, queen” or something. I think this social-media moment was an organic experience that I just don’t see other rock bands, even successful ones, pulling off well.

I think people probably picked up on that, too. We weren’t sitting for weeks before and going, “If we push this, maybe we can get to No. 1.” When I first saw the first chart that we were No. 1, I didn’t know what the chart was. I asked Craig, our label manager. I thought it was the Scottish chart or the vinyl chart. It wasn’t something that I had any inkling might happen at all. The photo they sent as the number trophy to get our photo taken with the day before, even at that point, we didn’t know if it was going to happen. I’m quite superstitious, and I thought this was going to jinx it. So if you look at the photo, Barry looks miserable because he was convinced it wasn’t going to happen. And this photo of us holding this trophy was going to exist to haunt us for the rest of our lives.

Will this success change your relationship with doing business through social media?

It showed how powerful it can be. I do think it’s hard to emulate something that was genuinely organic. But I’ll probably become pretty insufferable telling people about my book when that’s about to come out. I don’t think that it’s gonna go No. 1 in the charts.

This interview has been edited and condensed.