This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

It only takes a few years. An economic catastrophe brings on the partial collapse of American society. As the nation recovers, an ascendant right wing blames the crisis on China. In the years following, the United States is rebuilt as an authoritarian nation under the Preserving American Culture and Traditions Act, colloquially known as PACT, an expansive law that allows the government to ban books, monitor private citizens, and disappear political dissidents, all in the name of preventing the spread of un-American views, a category that grows broader by the month: “Appearing sympathetic to China. Appearing insufficiently anti-China. Having any doubts about anything American; having any ties to China at all — no matter how many generations past.”

This is fiction, obviously, even as it clearly brings to mind Japanese incarceration and the rise of McCarthyism as well as the wave of racist attacks on people of Asian ancestry since the pandemic began. The book in question is Our Missing Hearts, the third novel from author Celeste Ng, about a 12-year-old boy named Bird Gardner whose mother, a Chinese American poet, abandoned him and his white father three years before. Ng’s little mixed-race hero doesn’t speak Cantonese and doesn’t seem to eat Chinese food or know any Asian people. But his appearance alone — “the tilt of his cheekbones, the shape of his eyes” — is enough to subject Bird to the unifying existential threat faced by “anyone who might seem Chinese.” This spectacularly anti-Asian version of the United States betrays a new, more openly political ambition on Ng’s part: Whereas her previous work focuses on the experience of Asian Americans, she is now trying to write about Asian America itself.

The problem is that such a thing may not exist. It remains a very open question whether the disparate immigrant populations huddled under the umbrella of Asian American — a term coined by student activists at Berkeley in 1968 — have enough in common to justify a shared politics or even a shared identity. “Nobody — most of all Asian Americans — really believes that Asian America actually exists,” contends the journalist Jay Caspian Kang in his 2021 polemic The Loneliest Americans. For Kang, Asian American identity is a fantasy created by striving Asian professionals eager to reap the “spoils of full whiteness” while hiding behind a relatively mild, disorganized form of oppression that pales, literally, in the face of the systemic violence visited on Black Americans. “There are still only two races in America: Black and white,” he declares. “Everyone else is part of a demographic group headed in one direction or the other.”

What interests me here is not Kang’s argument per se — he is not the most persuasive writer on the subject, only the loudest — but rather the fact that both he and Ng, arguably two of the most prominent Asian American authors working today, end up placing their ideas on the shoulders of a mixed-race child. In the opening pages of The Loneliest Americans, Kang stares ambivalently at his half-Korean newborn’s “full head of dark hair and almond-shaped eyes,” wondering if she will one day inherit the whiteness that cultural assimilation and accumulated wealth will have bought her. Ng, for her part, is writing about a fictional mixed-race child, though she also has a half-Chinese son in real life, and in any case, as she herself observes in her second novel, Little Fires Everywhere, children are always fictional: “To a parent, your child wasn’t just a person: your child was a place, a kind of Narnia, a vast eternal place where the present you were living and the past you remembered and the future you longed for all existed at once.” Indeed, it is quite possible to read The Loneliest Americans as the author’s attempt to prove that his own mixed-race daughter has a serious shot at whiteness, just as it is hard not to read Our Missing Hearts as carefully positing the conditions under which Ng’s mixed-race son would be unambiguously Asian.

How is it that the mixed Asian child can seem quintessentially Asian American — as Asian American as apple pie, as it were — while serving as living proof that Asian America does not exist? It is not a question of whether Ng or Kang is right. The looming fact of racial admixture, especially with white people, may be said to form the grit in the pearl of Asian American consciousness today. This is true in brute demographic terms: Somewhere around 3 million Americans identify as multiracial people of East or Southeast Asian heritage, but our numbers are rapidly increasing, and almost half of all American-born Asian newlyweds have married outside their race. But this is also true — perhaps even more true — at the level of historical feeling, where the mixed Asian transforms the slow crush of assimilation into a dynamic and emotive physical presence. Even the most racially secure Asian Americans have been known to discover in their mixed counterparts a whiter version of themselves. This creature is beautiful and terrible, striated with desires that feel hard or wrong to name, a literal assimilation of culture, custom, and language, not to mention skin, fat, and bone. “If she can move freely between worlds, why can’t you?” the hero of Charles Yu’s 2020 novel Interior Chinatown asks himself, marveling at the sight of his mixed-race daughter with his immigrant father. “Maybe, if you’re lucky, she’ll teach you.”

That is a lot to ask of a child. It is a strange thing for fully Asian writers to look to mixed Asian people for relief from their racial anxieties when actual mixed-race Asians, who, it turns out, can write their own books, have little reassurance to offer. “I’ve always blamed my tendency to vacillate on my mixed ethnicity. Halved, I am neither here nor there, and my understanding of the relativity inherent in the world is built into my genes,” observes Jane Takagi-Little in Ruth Ozeki’s 1999 debut novel, My Year of Meats — an early instance of what we might call the “mixed Asian” novel. In recent years, this little genre has quietly bloomed, given life by a small cohort of novelists who write about characters that, like themselves, are of both white and East or Southeast Asian ancestry. (Accordingly, I’ll be using the imperfect shorthand mixed Asian to refer only to people of that particular ethnic makeup.) These novels are largely about unremarkable middle-class people without political or intellectual ambitions; what links these characters is not only a vague experience of racial non-belonging but also a gnawing uncertainty about how much this experience actually matters, even to themselves. Yet the mixed Asian novel has far more to teach us about Asian America today than Ng’s didacticism or Kang’s yawp does — precisely because it doesn’t have much to say about it at all. Asian America is not an idea for these authors but a sensation, a mild, chronic homesickness; indeed, to read the mixed Asian novel will be to ask ourselves if Asian America can be anything but a kind of heartache.

In the process, we may also learn to stop reading mixed Asians like novels. There is no better example of the latter tendency than Ng’s own debut novel from 2014, Everything I Never Told You, in which the favorite daughter of an interracial couple turns up drowned in a nearby lake. Lydia’s death is ruled a suicide, and readers are led to believe the girl cracked under competing visions for her life — her Chinese father’s eagerness for her to assimilate, her white mother’s desire for her to distinguish herself. But the truth is that Lydia never meant to kill herself at all. Instead, in a fit of Icarian optimism, she decided to swim the lake despite never having learned to swim. Her mistake is oddly conceptual: Lydia obviously does not need to literally survive a sink-or-swim scenario to figuratively stand up to her parents. It is as if the girl finds herself in a crisis of abstraction, rather than one of family pressures, and it is this essentially literary confusion — between narrative trope and material reality — that sends her to the bottom of the lake. Dragged down by the weight not of parental expectation but of her own waterlogged lungs, Lydia dies precisely as she lived: a metaphor.

So how does it feel to be a metaphor? There is, of course, a long history of tragic mixed Black characters saddled with symbolism in American literature: Nella Larsen’s 1929 novel Passing famously concerns a biracial woman’s doomed attempt to blend into white high society. The mixed Asian character, while a comparatively new phenomenon, has its own distinct literary roots. It is often forgotten that Amy Tan’s 1989 novel The Joy Luck Club — that classic of Asian American fiction — prominently features a mixed-race protagonist. “Most people didn’t know I was half Chinese,” remarks Lena St. Clair, noting that her resemblance to her mother is limited to dark hair, olive skin, and eyes that look “as if they were carved on a jack-o’-lantern with two swift cuts of a short knife.” As a child, Lena is expected to translate for her Chinese-speaking mother and frequently makes up lies; years later, she is languishing in a joyless marriage to her wealthy white boss, who insists they split household expenses. “I’m so tired of it, adding things up, subtracting, making it come out even,” she tells him, almost as if she is talking about herself. Her mother, deeply worried, compares her to a ghost.

In one sense, Lena is just a variation on a theme for Tan, who tends to view the character’s biraciality as a particularly obvious illustration of the more general plight of the assimilated Chinese American daughter. (If few today remember that Lena is mixed, this is likely because the character was rewritten as fully Chinese for Wayne Wang’s 1993 film adaptation.) “Only her skin and her hair are Chinese. Inside — she is all American made,” admits a different mother of her fully Chinese daughter. In fact, the members of the older generation of The Joy Luck Club often fret that their offspring are Chinese in appearance only, and they hand down sentimental stories of their tribulations in China out of a fear that their presumably mixed-race grandchildren — three out of the novel’s four daughters are at various points married or engaged to white men — will end up just as American as their mothers.

Yet at the same time, Lena represents a genuine antecedent to the protagonists of the mixed Asian novel. Like her, these characters are diffident, aimless, frustrated; they are stalled in their careers and ambivalent about their romantic partners, as if the acute experience of racial indeterminacy has diffused into something more banal. This is notably different from the “tragic mulatto” trope dating back to 19th-century fiction, in which a light-skinned character, denied the full privileges of whiteness by some remaining quantum of Black blood, descends into self-hatred, depression, or suicide. On the contrary, the mixed Asian hero is not a tragic mixture but an ironic one since, for the most part, she does enjoy those privileges — even when she doesn’t pass. But the fact that this dispensation may be conditional seems to linger in the mixed Asian psyche as a fuzzy, unsettled feeling that can manifest as anything from shyness to a fear of commitment. In Claire Stanford’s Happy for You, published this year, a 30-something half-Japanese woman named Evelyn impulsively abandons her unfinished philosophy dissertation to help a tech giant develop an app that tracks happiness — even as she is quietly anxious at the prospect of her boyfriend proposing. “I knew I was supposed to be happy about this,” Evelyn admits. “And yet when I thought about marriage, I felt only a hollow pit deep in my solar plexus, a vacancy that seemed to be mine alone.”

This emptiness — or really the displacement of racial or cultural emptiness into another, more general field of experience — is the first principle of the mixed Asian novel. Something is missing, but it isn’t clear what. Several characters end up trying to fill this hole with a child, as if rerolling the genetic dice will provide a glimpse into the origins of their own discontent. This is easier said than done, of course. Knocked up by her boyfriend, Evelyn will require an emergency C-section after the placenta suddenly separates from her quarter-Japanese fetus, endangering its life. “Somehow, my body had known I was not sure about the baby. My body had acted, unilaterally,” she thinks. Indeed, if mixed Asian protagonists struggle to rear children in these novels, that is because in many ways the mixed Asian still resembles a child, trapped in a state of perpetual immaturity by her failure during the critical window of childhood to inherit a clear narrative about her own racial identity. Willa, the directionless college grad of Kyle Lucia Wu’s Win Me Something, who works as a nanny for a wealthy white family, is pressured into joining the 9-year-old daughter’s private Mandarin lessons, where her precocious charge chastises her for asking questions in English. The scene is a perfect inversion of Willa’s kindergarten days, when she would proudly inform classmates that she didn’t speak Chinese. Now, to the Mandarin teacher, an ashamed Willa explains, “I didn’t grow up with my dad.”

Parental abandonment is a consistent theme across these books. Ozeki’s fourth novel, The Book of Form and Emptiness, opens with the pointless death by delivery van of the central character’s half-Japanese, half-Korean father. Willa’s Chinese father isn’t dead in Win Me Something, only absent, having left her white mother to marry a different white woman, resulting in a set of half-Chinese half-sisters. Of special note is Rowan Hisayo Buchanan’s Harmless Like You, about an irritable mixed-race art dealer and the Japanese mother who left him when he was a toddler. In high school, Jay begins to suffer from fainting attacks, and even as an adult he depends on a service animal, a sickly hairless cat that requires a daily suppository. Now, he struggles to relate to his quarter-Chinese, quarter-Japanese newborn daughter, whom he fantasizes about leaving with an expensive-looking white co-ed in the park. “You know the legend about how the goddess who gave birth to Japan had another child first,” he pontificates to his wife. “This baby of theirs, he had no bones. Hiruko. The name literally means leech child.” Jay is talking not just about his “leech-like” infant but about himself, as if racial amalgamation had resulted in a being whose lack of internal structure left it with only one purpose: to feed.

This brings us to a second principle of the mixed Asian novel: The more the mixed Asian allows the experience of racial dispossession to manifest directly, without displacement, the more this feeling takes on the form of something like a fundamental hunger. Many characters in these novels have strong feelings about Asian food — Willa treasures the memory of eating beef tongue with her father, while Jay nurses a self-parodying love of crab rangoon. By far the most interesting and sustained example of this trend is in Claire Kohda’s debut novel Woman, Eating, published this year, about a young mixed-race art-gallery intern in London who also happens to be a vampire. Lydia longs to sample the food of her late father’s culture — onigiri, soba, Japanese corn dogs — but human food is noxious to her. At the same time, she has never drunk human blood, having been raised on a strict diet of pig’s blood procured by her half-Malay, half-white vampire mother, who believes vampirism is a monstrous extension of colonial greed. Now, living on her own for the first time, Lydia slowly begins to starve; unable to procure fresh pig’s blood from her local butcher, she resorts to buying a powdered version online, then to draining a dead duck she finds along the river. At the novel’s end, when she finally drinks the blood of a white art curator, a rapturous Lydia discovers his blood tastes like everything he has ever eaten, including not only Japanese food but Malaysian delicacies like pandan, “something unfamiliar but at the same time deeply familiar, something I didn’t know I craved.”

There are two ironies here. The first is that Lydia can taste Asian food only through acts of terrific violence that bear an uncomfortable resemblance to the original colonial act. Lydia is also of European stock, after all, and it can be difficult to parse the reclamation of heritage from the crime of cultural theft — hence the narrative contrivance of her inability to source pig’s blood, which renders her actions understandable (she’s very hungry) if not exactly justifiable. For the second irony is that coagulated pig’s blood, without the addition of fillers as in blood sausage, is eaten as a food unto itself in several Asian countries, including Malaysia; perhaps some of Lydia’s existential problems could have been solved simply by access to a well-stocked Asian grocer. But this is precisely why food matters so much to the mixed Asian: It places the desire for culture inside the body, out of the reach of any potential accusation that she is, as it were, appropriating herself. Compare Michelle Zauner’s 2021 memoir Crying in H Mart, named for the beloved Korean American grocery chain, in which the half-Korean musician reflects on the death of her mother with reference to the fermentation process involved in making kimchee: “The culture we shared was active, effervescent in my gut and in my genes, and I had to seize it, foster it so it did not die in me.”

This is poetic but not exactly plausible. There is really only one craving that the mixed Asian invariably carries in their body, and it is not the hunger for cultural memory. “There is no way to look at the face of a mixed-race person and not be immediately reminded of sex,” Ozeki observes in her short nonfiction book The Face: A Time Code — though this reaction may be more unconscious today than it was when Ozeki was growing up in the ’60s. Almost all children, of course, are proof of sexual congress; what the mixed person suggests is not just that people of different races can be attracted to each other but also, more discomfitingly, that people can be attracted to the idea of race itself. Indeed, a striking peculiarity of the mixed-race Asian is that almost any sexual attraction he experiences will by definition be interracial, given that he inhabits no clearly defined racial category to begin with. What this means is that racial difference is an inescapable factor in the mixed Asian’s romantic choices. The wisecracking author in Peter Ho Davies’s The Fortunes considers himself “immune to the Western fetish of otherness, even if — perhaps because — his father wasn’t,” though what this means in practice is that “he’s never been attracted to Chinese girls” and he calls his white wife his “occident waiting to happen.” This dilemma — call it compulsory exogamy — is taken to almost satiric levels in Buchanan’s Harmless Like You, in which Jay putatively wriggles out of the problem by marrying a half-Chinese woman who so strongly resembles him that a friend is reminded of “the Siamese cats in Lady and the Tramp.” But this is not so much a refuge from the dilemma as a confirmation that even the most precisely calibrated same-race desire is still, for that very reason, a desire for race.

If there is a final principle of the mixed Asian novel, it is that no amount of resemblance can guarantee relation — to a parent, to a culture, to a race, or a racial politic. It is not every mixed-race Asian who can, for instance, walk through Chinatown like Bird in Our Missing Hearts and feel “oddly at home” surrounded by faces like his mother’s. Compare this with Willa in Win Me Something, who anxiously researches restaurants online when her younger half-sister Charlotte proposes they meet for soup dumplings. “Sometimes being in Chinatown made me feel a melancholy indigo, skittish with a feather-brushed sadness,” Willa admits, recalling the time a man hawking newspapers in Chinese fell silent as she walked past. At the restaurant with Charlotte, who grew up with their Chinese father, Willa puzzles over their differences. “I didn’t feel envy. It was just that I wanted her to know what it was like for me,” she thinks. “If I could have her understand anything, it was this: Do you know the feeling of home that you have? I don’t have that.”

But the difference between Willa and her sister, who is just as mixed-race as she is, is the whole point. At the lowest limits of every bond of kinship, one finds not some cultural or hereditary bedrock but a small infinite ravine that must be leaped across, again and again, through acts of will. This is not to say that the only thing standing between the mixed Asian and racial homecoming is her reluctance to come home — quite the contrary, as the mixed Asian novel amply demonstrates. But what these novels also force us to admit is that there is no racial belonging without the desire to belong, that the desire to reach, not without risk, across differences of physical appearance, personal history, and material circumstance is a necessary, even critical, component of race — not just for mixed-race people but perhaps for everyone.

Early in The Loneliest Americans, Kang clarifies that the title refers to “the loneliness that comes from attempts to assimilate, whether by melting into the white middle class or by creating an elaborate, yet ultimately derivative, racial ‘identity.’ ” Indeed, Kang so ardently believes in a universal desire to be white among so-called Asian Americans that he reflexively dismisses every indication to the contrary — a taste for tapioca pearls, support for ethnic-studies programs — as little more than yellowface. Eating at an Asian food court in Berkeley, Kang cannot conceive of why a nearby group of Asian undergrads would choose to sit together. “Their insularity feels banal and unwarranted,” he complains. “If you’re just going to speak English, dress like everyone else, and complain about schoolwork like every other Berkeley student, what, exactly, is the culture you’ve created?”

We are very good these days at providing elaborate explanations for why people of color may want to be white — an assumption we often make not out of rigor or intellectual bravery but for our own analytic convenience. The world is simply much harder to understand when one stops treating white supremacy like a gas leak — invisible, omnipresent, and expanding to fill every void — and more like an oil spill: sprawling and massively destructive but also crude, combatable, and, most important, easily surpassed in scale and complexity by the ocean itself. It is a sad irony of The Loneliest Americans, for instance, that it never occurs to Kang to ask whether his own half-white daughter might one day want to be Asian. The fact is that a certain minority of people, thanks to an accident of birth, will always find themselves in the curious position of being made to move, just a bit, along the weird, curved plane that is race in America. This movement defies the Euclidean assumption that racial identity always exists in direct proportion to racial assignation — “the color of one’s skin,” as American politicians like to say. It suggests, in other words, that a certain small measure of freedom may inhere in the concept of race itself.

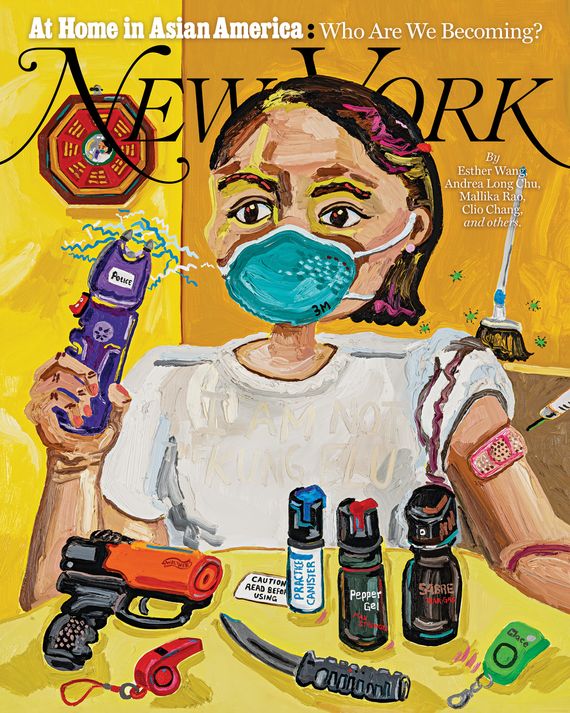

To be clear: Such freedom, if it exists, would be largely subjective. It would not be sufficient on its own to alter the objective realities of racism, nor would it have any direct bearing on liberatory struggles; above all, it would not justify race fraud. This freedom would simply remind us that white supremacy is neither the only nor the best conceptual yardstick for the lived experience of people who are not white — not least because, as the mixed Asian novel shows us, we cannot know in advance who those people are. It is undoubtedly true that race in America is created and maintained through racist violence. It is, however, no contradiction to say that race, once people start living with it, can no longer be reduced to that violence for the staggeringly simple reason that people do live with it, every day, gradually patching together new, often temporary worlds of experience in which race may be felt as something other than a target on one’s back (or, for that matter, a gun in one’s hand). It’s worth noting that, at the end of the day, Ng and Kang actually agree that racial identity can be bought only through racism; they are merely, to quote the old joke, haggling over the price. But what this assumption yields is a thin, abstract concept of Asian America, one that is so hostile to actual human beings that it recognizes them only when they are in pain. This is why the question “Does Asian America exist?” is the wrong one; it is a bloodless logic game masquerading as a political problem.

Here is the better question: Do we want to be Asian Americans? I don’t mean this in a voluntaristic, do-you-believe-in-fairies sort of way, but as a real, honest question: Do people of Asian ancestry in this country want to be Asian Americans? The question is not why a mixed-race person should “get” to qualify as Asian despite, for instance, never having been bullied at school or attacked by a stranger; the question is why we cannot imagine any other way to be Asian. And if there is one conclusion to be reached from the mixed Asian experience, it is this: People want race. They want race to win them something, to tell them everything they were never told; they want friendship from it, or sex, or even love; and sometimes, they just want to be something or to have something to be. I do not mean that Asian America will suddenly appear on the horizon tomorrow if enough of us choose it tonight. What I mean is that many people across the country, including many of us who are mixed, are already choosing it, and it is enough for now to ask why. There is, after all, a reason that people sit together: They don’t want to be alone.