This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

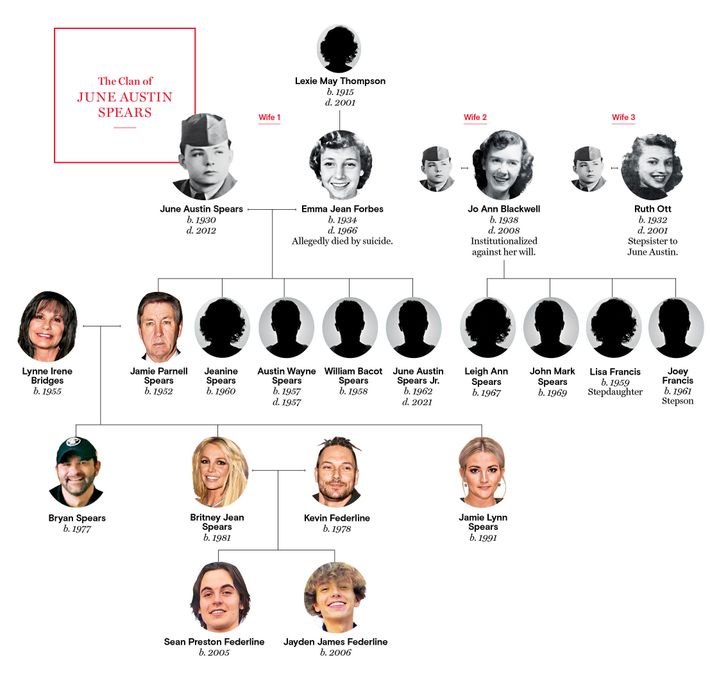

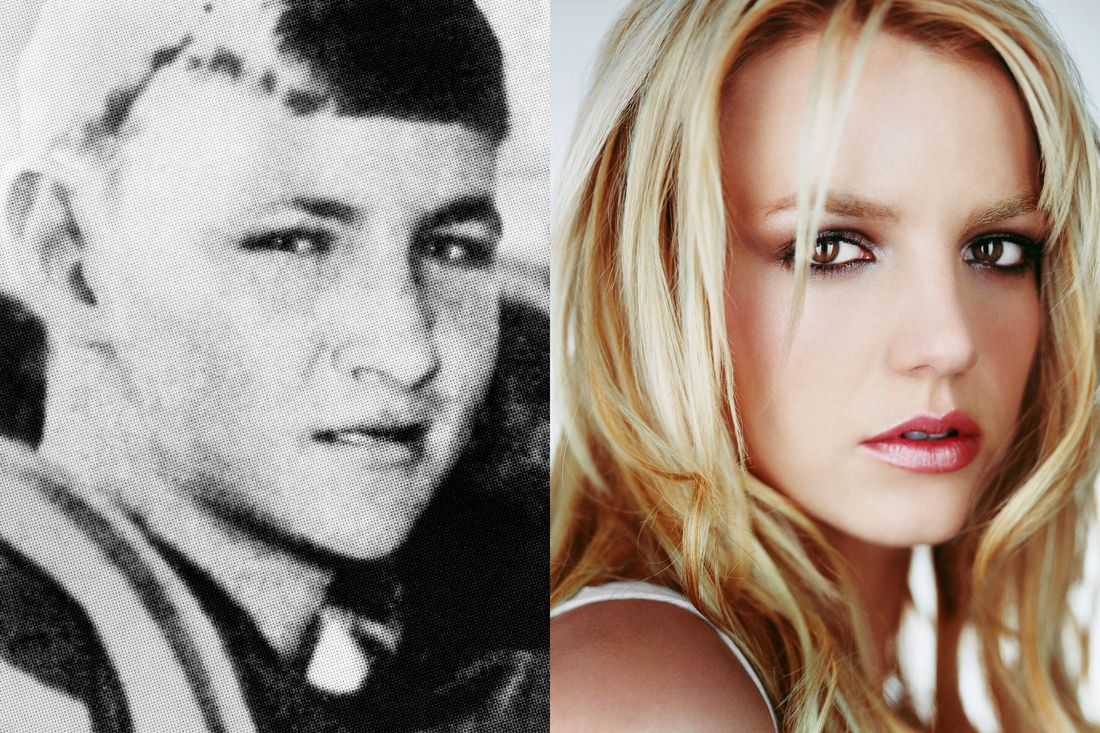

On May 29, 1966, Jamie Spears was 13 years old, an eighth-grade honor-roll student small for his age, the son of a father a friend describes as “a fireball on steroids.” Jamie had three siblings, ages 3 and 5 and 8, and there ought to have been another one, the second born, but Austin Wayne Spears died at 3 days old, leaving Jamie alone again with his parents. The family lived near the Mississippi line in Kentwood, Louisiana, 70 miles from the hospital where Austin Wayne was born, far from anything then and far from anything now. Generations back and generations forward they lived and would live here, in Tangipahoa Parish, in the bare little towns that ran along the train tracks. The baby had been buried below an oak tree in a small cemetery loud with the buzzing of cicadas. Jamie’s mother was named Emma Jean Forbes, and everyone called her Jean. She was small, like her husband and son, and she was blonde, and she had married when she was 16 years old, which was older than her mother had been when she married in Mississippi. Later, her husband would tell the coroner that Jean had tried to kill herself three times, but whether to believe her husband, and what part he might have played in what unfolded in May 1966, remains in question.

Jean’s husband, Jamie’s father, was named June Austin Spears, and that’s what they called him, June Austin. June Austin was born in 1930 not far from Kentwood, a few miles from where a Black family had been purchased for the sum of $20 a solid 60 years after emancipation. June Austin had a mean streak, but June Austin would live for a very, very long time, and by the end of his life, many people would simply remember him as a man who loved to fish. As a baby, Jamie had his mother all to himself; June Austin was in the Air Force and didn’t meet his son until Jamie was a year old. June Austin was hired as a police officer down in Baton Rouge, was fired after either he or someone else on his team shot at an innocent man, and then was reinstated, but by May 1966, he was once again no longer working as a police officer. It was a Sunday afternoon when Jean Spears drove the empty streets sliced through slim shimmering pines to the little cemetery where her infant son was buried. The story the papers would tell is this: Jean Spears walked from her car to her son’s grave carrying a 12-gauge shotgun, a long hunting rifle that probably would have been over two feet long. She stood on the little piece of land where she had watched them lower her baby into the ground and pointed the gun up so the butt was in the dirt and the barrel pointed at her. She loaded it with 16-gauge shells, technically too small for the gun. She removed her shoe, pressed the trigger with her toe, and fell to the ground, where she would remain until someone found her the next morning and police traced the parked car back to the family.

“I have been very good,” Jamie’s little sister, Jeanine, wrote to Santa Claus the following year. “Please bring me a Lucky Locket kiddle doll.” Eight months after their mother disappeared, Jamie and Jeanine and June Jr. and William watched their father marry another woman in the home of her parents in Kentwood. The woman was also from Kentwood, a town of not quite 3,000 people and a few last names reflected back at those people on the street signs and the businesses on those streets: Harrell, Spears, Easley, Ballard. Jo Ann Blackwell would be June’s second but not last wife. It was, the paper said, a “quiet, impressive rite,” attended not only by Jean’s children but by their new stepsiblings, Lisa and Joey.

Jo Ann Blackwell was 28. Her brother Arlan was married to June’s stepsister. She had striking blue eyes, and she loved Willie Nelson, and she came from a well-respected religious Kentwood family. In high school, she had been named the Betty Crocker Future Homemaker of Tomorrow. The home she was now expected to make included Jamie and Jeanine and William and June and Lisa and Joey and, very quickly, the two children she would have with June Austin: Leigh Ann and, the year after, John Mark, whose eyes were as blue as hers. In later years, and in court, June Austin would number his children at ten, but it was never clear whom he was counting.

Jamie Spears had a Louisiana drawl so deep a documentary in which he later appeared would include subtitles. He had delicate features of the kind a mother would dote over; he did not look like the sportsman he was. The September after Jamie’s mother died he ran three-on-threes on the patch of grass next to Highway 38 in the wet heat of the Deep South. After practice Jamie came home to June Austin, and June Austin would make him practice even more, beyond exhaustion. Sometimes his best friend, Sandy Jones, would come over after games, and June Austin would holler at the both of them and yank their hair and then take them out to dinner. June Austin had become a boilermaker, a job that involved shoving himself into small spaces and shooting fire at sheets of steel. When June Austin traveled out of state to look for work, Jamie spent time with Jean’s mother, Lexie, a still-young woman who would outlive all three of her children. It had been at Lexie’s house that the body of his mother was displayed after her death.

The people of Kentwood raised Jamie Spears, and he returned the favor by entertaining them. It didn’t matter what game he was playing, Jamie was beautiful to watch. “Jamie could shoot the hell out of a basketball,” says Collis Temple, who played alongside Jamie and then for the San Antonio Spurs. “He was one of those special athletes, okay? There’s some guys who have this hand-eye. That’s special. He could shoot pool, he could play Ping-Pong, he could throw a football, he could shoot a basketball, he could throw a baseball. Some people have that, some people don’t. It’s called It.” There was no three-point line in Kentwood in 1969, but if there had been, Jamie Spears would have sunk untold numbers of three-pointers. He once scored 47 points in a single game. But it was football June Austin cared about, and there Jamie was the quick-footed quarterback calling the shots, shooting perfectly angled passes on a field lined with parents who knew exactly how his mother had died.

The football coach was Elton Shaw, a reassuringly solid man who had been drafted by the Green Bay Packers and come home to Kentwood. Elton Shaw was the same age as June Austin and a man no one would call soft, but he thought June Austin was far too hard on Jamie, and he tried, when he could, to stand between June Austin’s rage and his star quarterback. Home games they played “under the tank,” on a ragged field beneath a blue water tower bearing the team’s name. Wherever they were, June Austin was in the stands, and you knew it. “A fireball, that he was,” says Shaw. “He would fight. Every time we went somewhere, we were going to get in a fight, because somebody was going to jump on him, because he was the littlest in the crowd. Didn’t know that he was the baddest son of a bitch in Louisiana.”

It was challenging for people to mention Jamie’s talent without mentioning his size. “This little guy runs well, and we just don’t know but what we might use him as a running back,” a Southeastern Louisiana University coach told the Baton Rouge Advocate in 1972. “This Spears is a fine competitor,” an entirely different coach had told the same paper a year before. “While he’s a small boy, he can do it all.”

A football team is a social unit in which everyone has a place. Jamie’s was at the top. In 1969, the schools finally integrated. Jamie showed up to practice to find a second football team in the gym — players from the Black high school across town, including star quarterback Collis Temple. Jamie stayed quarterback. Collis played basically every other position. The team took the state title before a crowd comprising both Black and white Kentwood. Jamie and Collis were champions.

Louisiana named Elton Shaw coach of the year; pictured under him in the Kentwood Ledger was Jamie Spears, all-state quarterback. It was a positive story amid much hostility in 1969, and it might have been repeated in 1970, but by then Shaw, Jamie, and Sandy Jones had left Kentwood High for a private school or, as Collis Temple calls it, a “racist-ass school,” the school having been built, as so many were, in the general mania for private-school-building that pervaded Louisiana at the time and attended exclusively by white students. The people who established Valley Forge Academy offered Shaw more than double his salary. He had four children to feed and was making nothing much at Kentwood High. He took his star quarterback with him to play for a new team, which, lest the school’s reason for being seem too subtle, would be called the Rebels.

In the summer of 1970, Jo Ann Spears had been married for three and a half years to June Austin, a period during which, she later claimed in court, he had beaten her, failed to support her, “constantly defamed her,” and “committed numerous acts of cruelty toward her.” According to her children, June Austin institutionalized Jo Ann against her will at the psychiatric hospital known as Mandeville, the kind of place he referred to as a “nut house.” He then simply left, moved to North Carolina in search of work. He took his three younger children with him and left Jo Ann with her four biological children, two of whom were his. He was joined in North Carolina by Ruth Ott, who was his mother’s husband’s daughter, which is to say his stepsister. Soon after that, June Austin divorced Jo Ann and married Ruth, and the two of them lived for a time in the home of his mother and her father.

It was when June Austin was in North Carolina with the stepsister who would become his wife that Jamie was back in Louisiana staring out the window of a speeding car with two friends, William Easley and Joseph Lee. Easley was driving east on Route 16 in Amite, a bit south of Kentwood, toward a little bridge that spans the dark, winding mire of the Tangipahoa River, and he failed to account for a slight curve, at which point the car slammed into a concrete railing and split in half, sending the engine twirling into the muck of the river and the seats, with the boys in them, nearly to the other side of the bridge. Easley died. A patch of Jamie’s hair was, in the words of a teammate, “skint off his head.”

Shaw brought Jamie home to the low-slung brick house he had built himself, which was full of his own boys already. “We called his daddy,” says Shaw, “and oh, his daddy just went ballistic.” His response to his son surviving a deadly crash in which he lost a friend was to berate him for being out with those boys. “Jamie started crying,” Shaw says, “so I called June Austin somewhere in North Carolina. I said, ‘If you don’t call this kid back here, apologize, and talk to him like a human being, I’m going to catch the next airplane to wherever and whip your little ass.’” June Austin apologized. Jamie couldn’t play in the next game, in part because he couldn’t place his helmet over the wound. Two weeks later, he was back in position. Less than a month after the death of his friend, and four years after the death of his mother, before a crowd of thousands, Jamie Spears willed himself onto the field and won the team a championship.

Britney Spears is her father’s daughter: not a songwriter, not a diarist, but a dancer, an athlete, a woman so brilliantly embodied that every woman of her generation recalls the particular way she walked down a high-school hallway. The shock of this absolute command does not diminish with time. There is, in video after video, tour after tour, that crisp effortlessness, the sense of a body hitting each beat hardest yet trying least, a rock-steady presence never lost in the sweep of choreography. Here are a mind and body so perfectly synced that everyone else begins to look as if slowed by some invisible static, an affliction from which Spears alone has been spared. She could have been an elite gymnast had she chosen to, but there was something about her stare of which gymnastics could not make use. She became instead the pop star who smuggled more movement into every count, faster and better, the rare singer just as percussively corporeal as the professionals dancing behind her.

People would ask what it was that Lynne Bridges ever saw in Jamie Spears, but it was surely this, It, “an average sized guy,” as Lynne would write, who could “run circles around huge ball-players.” Jamie Spears was, by this time, lost. He had enrolled at a local college as a football player, but Jamie Spears was 161 pounds and five-foot-nine, dimensions perhaps no amount of training or determination could overcome. He broke his leg in the second game of the season. He dropped out and never went back. His life as a locus of admiration was permanently over. Jamie married a woman from Kentwood, a smart girl he had known all of his life who had made the honor roll in eighth grade right along with him. He left town, got divorced, and moved back to Kentwood. In 1976, he and Lynne Bridges were both living in the town where they had basically always been. Jamie made her laugh and took her dancing. She eloped against the wishes of her parents, who would have seen a former jock brought low by injury and circumstance, a divorcé with a dead mother and an abusive father married to his stepsister.

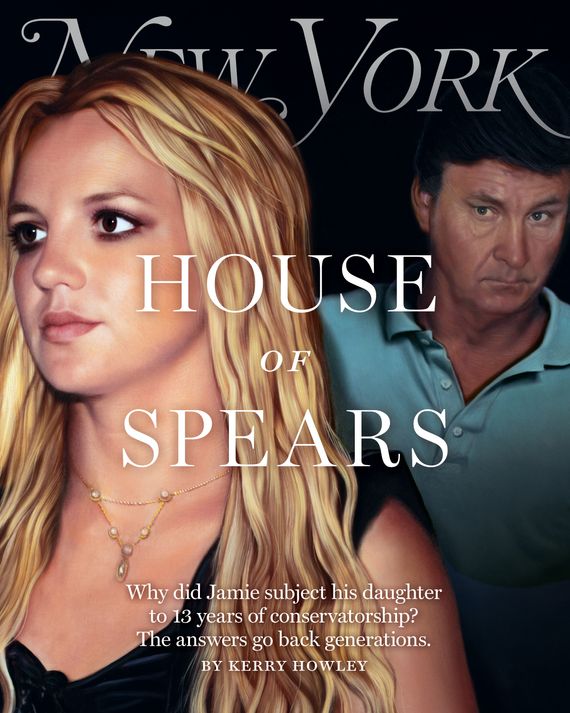

Years later, when people heard the haunting details of the conservatorship, there would be an impulse to assume that it was in some sense necessary and that somewhere it had just gone bad. But the conservatorship of Britney Spears is not a conflict that accrues moral complexity under further investigation. This is not the cloying tendency of American fans to conjure obstacles out of extreme privilege, not the “prison of fame” or the isolation of superstardom or the trials of being trailed by paparazzi. It is a matter of an extraordinary woman deprived of basic human rights over a period of 13 years. The question worth asking is not whether the conservatorship was necessary or right — it was not — but why a father would seek to exert dictatorial control over the hour-by-hour life of his adult daughter. “Why are all my doings always blasted?” Britney Spears, now estranged from all of her family members, asked in an Instagram post in July. “How come not one person knows my sister is building a huge home in Louisiana??? How come their lives aren’t exposed? … I would thoroughly enjoy showing up at my families home to see what secrets they’re hiding.”

Transparency has not been the way of Britney’s family. “My daddy’s people have been in that area as far back as anyone can remember,” Lynne Bridges Spears writes in her memoir. Lynne’s daddy was a rigid Christian dairyman who served in the Army in London in World War II, where he met a London girl and told her he was a landowner — “hundreds of acres of Louisiana soil” — which was, in its own particular way, true. He married her and brought her back to his farm in Kentwood, which did not, in the end, resemble anything befitting British gentility. “Where are all the lights?” she asked on the drive home, in thick air heavy with gnats, over dirt roads, toward all the farmwork and tragedy that lay ahead. She wept every night and over the next three decades made it back only once.

Lynne is “full of admiration for the British way of life” but considers Kentwood superior to any place in the world. When she was 20, a piece of tractor equipment fell on her brother. She sped with him to the hospital down Highway 1049, a road with houses set far back on either side and no sidewalks to speak of, such that the only way for a child to ride a bike would be to share space with cars. “As I was rounding the curve,” writes Lynne, “an oncoming car was coming in the left lane … I could see two young boys riding their bikes on the road … I had a sick sensation that I would hit one of them, that it would be impossible not to … a 12-year old boy … was hit.” Another way to say this would be that Lynne’s car slammed into a little boy. The boy was named Anthony Winters, his father was the first Black police officer to serve in Kentwood, and his mother was named Yvonne. He was, Yvonne told me, “just a normal teenager.”

Across town, Jo Ann went back to Mandeville, and June Austin collected his children Leigh Ann and John Mark. These children, he told the court later, “were in such physical and mental state,” their heads “full of fleas and nits and lice.” He took them to New York in search of work, though he did not have permanent custody. When he returned to Kentwood some years later, Jo Ann wanted her kids back. June Austin would not give them back, and so they went to court.

The court interrogated Jo Ann as to her fitness as a mother.

“In your motion that is before the court today,” June Austin’s lawyer said, “you just stated that you had been in Mandeville and you referred to a nervous disorder.”

“I have never referred to it as a nervous disorder,” Jo Ann said.

“That was the term used in your petition.”

“Well that is a very broad term.”

“Could you be more specific.”

“Well I don’t know how much time we have for this,” she said, “but if you want to hear it I am manic depressive.”

The court awarded custody to June Austin, the man who had technically kidnapped them. Leigh Ann, Jo Ann’s daughter, would later say June Austin sexually assaulted her multiple times. John Mark, Jo Ann’s son, would call him a monster who beat his children and drove his wives to madness.

Lynne was pregnant within a month of marrying Jamie. They lived in Lynne’s trailer, and he brought her fried chicken and frozen grapes until the arrival of Bryan James, at which point he started drinking. “In our lives together,” Lynne writes, “if someone was sick or even dying, Jamie would find a way to act up and direct everyone’s attention to him.” In 1978, Lynne’s father was crushed to death by his own milk truck. Jamie disappeared for a week. Lynne went back to school, and Jamie told her she was too stupid to graduate.

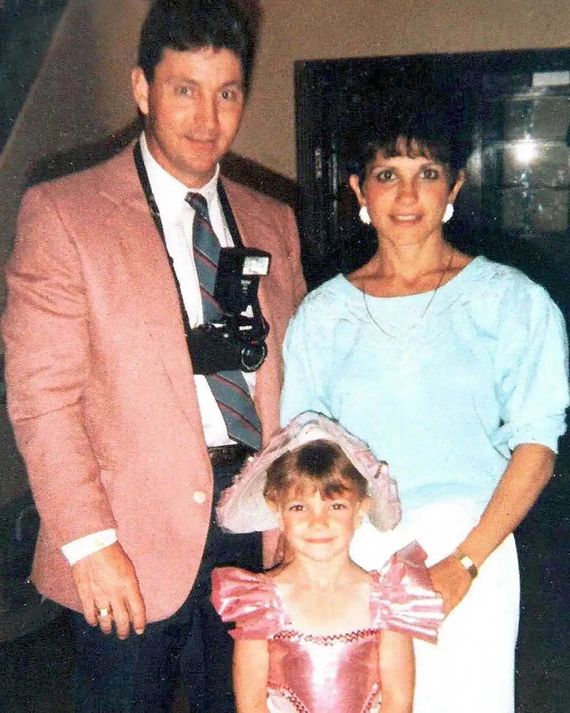

Jamie Spears promised to stop drinking, got drunk, and made more promises. On the baby’s third Christmas, Jamie was not, according to a court filing, at home with his family. He was at Baby Tate’s Bar in Tangipahoa, where someone in this exceedingly small community evidently told Lynne he was “hugging, kissing, and fondling” one Cindy Ballard, whom he then took back to his place, Lot 13 in Simpson’s Trailer Park. Lynne filed for divorce and a restraining order alleging he might become violent when he heard about the divorce. June Austin showed up with his third wife and begged Lynne to give Jamie another chance. Lynne retracted her filing and had a child the next year. By the time she was a teenager, this child would look an awful lot like Jamie’s late mother, but they would not have known that when they named her Britney Jean.

Jamie promised to quit drinking. He “rededicated himself to God.” He tried to drive drunk with 5-year-old Britney in the car, and when his little brother Willie reached for the keys, Jamie punched him in the face. When Lynne worked, she left Britney with Jean’s mother, Lexie, who would have noticed that Britney had inherited Jean’s smile, eyes, and nose. Lexie had a crawfish place called Granny’s Seafood Deli; Jamie worked there on and off, as did little Britney, which is to say that Jean’s mother, Jean’s son, and Jean’s granddaughter all cooked together, four generations of which one had been horrifically lost. Britney worried about having her grandmother’s name; she thought perhaps it was cursed. Britney sang at the First Baptist Church, and after church everyone went to Papa June’s for dinner, where he lifted Britney onto the dinner table and she sang some more.

Jamie was fitfully employed as a boilermaker and a builder and a cook. Later, people would try to argue that he and Lynne were stage parents, but when Britney, who had excelled at Bela Karolyi’s elite gymnastics camp, wanted to stop taking gymnastics altogether, she stopped. She was, her teachers said, internally motivated, a perfectionist, a workhorse. Jamie told anyone who would listen that his daughter was going to be a star. Jamie and Lynne paid their taxes irregularly. They missed car payments. They made unorthodox financial choices, like paying for their daughter’s various lessons and competition-related travel instead of all their taxes, and sending their children to a private school established on the eve of integration, where, when asked whether the school served any Black children, an administrative assistant responded that they had children with the last name Black. They spent all their money on their children; they believed utterly in Britney’s future stardom. Later, the story everyone told was of a family that could barely feed itself, but they were not poor. They were messy. They lived in a solid home with long front windows and a big yard. Lynne owned a day-care center, and Jamie started a gym that went out of business.

Bryan, age 8, broke his hand, his leg, and his arm riding a motorized dirt bike; he was placed in a half-body cast. Bryan, age 10, fell riding the same motorbike and was so thoroughly burned by the exhaust pipe that he had to have the burn regularly cleaned at the hospital as he screamed. Jamie promised he wasn’t drunk as Lynne watched him stumble in front of a mirror. They were dressed up, on their way to Jean’s mother’s birthday party. Britney beat 20,000 other kids to be cast in The Mickey Mouse Club, and Lynne’s mother died in a swimming pool. Jamie got a vasectomy but did not appear for his follow-up appointment. Jamie and Lynne had another daughter, whom they named Jamie Lynn.

“When he was around,” Jamie Lynn writes of her father, “he spent much of his time in a chair trying to convince everyone else he wasn’t drunk.” Lynne began teaching Britney how to drive with Jamie Lynn in the car. “No one wore seat belts back then,” Jamie Lynn writes; this would have been 1997. Britney swerved over the midline, nearly hit a car, and drove into a ditch. Lynne switched places with Britney in the car so her husband wouldn’t know she was letting Britney drive. “Momma always cared more about Daddy’s feelings than doing the right thing,” Jamie Lynn writes. “Momma often put us in a difficult position rather than confronting the situation head-on.” While she was shopping with Jamie Lynn, Lynne’s card was declined at the Limited Too. Jamie and Lynne defaulted on a mortgage; the land was seized and auctioned off. Three years later, a sheriff took their Ford Probe from the body shop; they owed $10,000. Jamie and Lynne filed for bankruptcy in July 1998. “… Baby One More Time” was released three months later, when Britney Jean Spears was 16 years old.

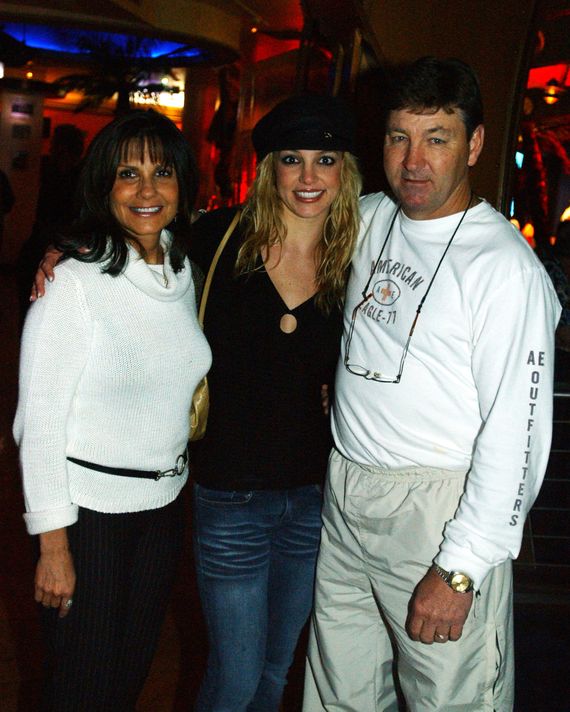

Britney Spears is a 40-year-old woman who has enjoyed a total of nine years of independence from her parents’ control. The years went like this: … Baby One More Time sold 11 million records, Oops! … I Did It Again 9 million. Britney debuted at No. 1. According to her sister, Britney told her mother she would build her a new house on the condition that she divorce her father. Lynne divorced him, moved into the Kentwood mansion Britney built her, and let Jamie come over. Jamie lived in Britney’s childhood home, the interior of which was now covered, presumably by him, with Britney’s face: ticket stubs and records and concert posters and magazine covers and framed pictures. Her bedroom was bare because everything in it had been relocated to a model bedroom in a little museum downtown. Some girls who had just graduated from a Catholic high school in New Orleans drove to Kentwood to the house where Britney had grown up. Jamie emerged, loosed four dogs, and pulled a gun on them.

Britney Jean Spears lived in a 9,000-square-foot house cut into the Hollywood Hills. She starred in a road movie written with the purpose of her starring in it. She lifted aloft a seven-foot Burmese python known as Banana and draped it over herself as she moaned “I’m a Slave 4 U” and hit every step.

When he was in L.A., Jamie seemed to become only more determinedly Kentwood. Sometimes he found work as a cook. He cooked venison sausage and crawfish and pulled pork and quail breast with bacon. There was no secret, he said. It was simple southern food, like the kind Jean’s mother would cook with him. Jamie went to rehab in 2004 and was sober for a while and found God again. He became entangled with the Evangelical wife of a Tennessee pastor, a high-school graduate who rode a Harley and claimed to “love nothing more than ministering to other women.” The pastor’s wife owned a business-management firm; she became Jamie Lynn’s business manager. She loaned Jamie money, and he paid her back.

Britney married her backup dancer, had two children in quick succession, divorced the backup dancer, and became what the press called erratic and unstable and, very often, crazy, though to many people later on, she looked like a person going through her 20s. She shaved her head. She spent a month in rehab. She performed lethargically at the VMAs, a step behind, as if thinking about something else. She missed a court-ordered drug test, was accused of driving with her kids without a California license, and lost custody of them. She began living with a man she met at a nightclub, Sam Lutfi, who called himself her manager. The press often quoted people from Kentwood saying that Britney Spears needed to “come home.” But Britney Spears did not go home to Kentwood. Kentwood came to her.

In 2007, Britney Spears, 25, lived in a 7,500-square-foot Studio City mansion with a pool and a yard and space shielded by walls of greenery. She found out that 16-year-old Jamie Lynn was pregnant by reading OK! magazine. From afar, Lynne and Jamie felt Lutfi was controlling Britney: In a petition for a restraining order, they accused him of drugging their daughter into compliance, crushing up pills and putting them into her food, disabling her cars, calling her a bad mother and a whore. (Sam Lutfi’s lawyer denied these allegations.) At the end of a supervised visit with the boys, Britney locked herself in a bathroom with her baby. Giving him back was like losing a child every single time. Someone called the police and Britney was strapped to a gurney, hospitalized, and deprived of further visitation rights. The press referred to this as a meltdown, the modern term for nervous disorder.

“Something drastic would have to happen for Sam to lose control and for Jamie to gain control of his daughter,” Lynne writes, laying out what appeared to her to be the available options. Jamie, who had not been central to Britney’s career, not gone to Orlando or New York, was suddenly dramatic, obsessive, engaged. Something had shifted. His daughter had in some sense lost her children, a tragedy that could drive a mother into darkness. “She used to talk about how she couldn’t believe she was named after her grandmother who killed herself,” Jamie’s brother William said at the time. “Now we are worried the same will happen to her.” He was talking, at the time, to the pastor’s wife. (Her attorney says she did not push for the creation of the conservatorship.) Jamie was praying and fasting. It was in times of sickness, Lynne said, that he made his presence known.

Lynne came to visit Britney at the mansion, and when the gates opened, Jamie sneaked in behind her. At the door, the manager, Sam Lutfi, told Jamie to leave; Britney, he said, was afraid of her father. Jamie, the manager alleged in court, lunged at him, fists balled, spitting, shouting, and chased him around Britney’s kitchen island. He was going to beat the hell out of him. Security removed Jamie. The manager, Britney, and Lynne went to Rite Aid, where Britney bought a lipstick. The next morning, Jamie showed up and punched the manager in the solar plexus.

Three days later, Britney was again hospitalized against her will. June Austin, 78 and a widower three times over, said he was worried about her. “She shouldn’t go in the nut house,” he said. “Sometimes you come out worse than you go in.” It was the same year that Jo Ann, the woman June Austin had had institutionalized against her will, died in poverty. She had become, late in life, highly medicated, vacant. Her daughter had her grave inscribed THY TRIALS ARE OVER, THY REST IS WON.

Jamie submitted a document requesting that he become Britney’s conservator, though this was not to be a typical conservatorship because the conservatee was not elderly, but a 26-year-old woman capable of generating hundreds of millions of dollars. The document suggested Britney suffered from dementia; the accuracy of this diagnosis would be contested. On the Today show the pastor’s wife instructed everyone to pray to God to “intercede” for the Spears family. Jamie put the pastor’s wife’s company in charge of Britney’s finances; her company would be intimately involved in the day-to-day conduct of Britney’s life. Britney was no longer in control of herself or her money.

In January 2008, Jamie had to sneak into Britney’s home. Shortly thereafter, Britney’s conservator walked freely into her large, dark, Italianate kitchen. He was hovering over a stove in a white tank and jeans, with both eyeglasses and sunglasses hanging around his neck, beside the island around which he had chased the manager. He had won. “I’m ready to go. I’m making my baby some cheesy grits,” he told a documentarian. “Grits is a old southern tradition. She’s been eating them since she was born, she loves them. I don’t have no sprinkle cheese, so I’m just putting her momma’s old-timey way here, doing it with just some Velveeta in it.” He licked some off a spatula, walked the grits to a bathroom where Britney was having her hair dried, and handed them to her. He wasn’t sure there was enough butter and cheese, but she said there was. She called him “Daddy”; he called her “Baby.” He could be brought to tears just looking at her, how beautiful she was. “Daddy!” she said of his tears. “I don’t understand how he can be such an asshole and then so nice!” When he tried to give creative input — he thought she should be thinking about other women as she sang “Womanizer” — she nodded and looked away, the way you do when a man traps you at a party, and made fun of him later. She and the team yelled at each other. He called her fat, she mocked him to his face, he cried. “Gimme that phone,” he said. “No, Daddy!” she replied.

There did not seem to be anything in Jamie that craved opulence. He did his own laundry when the others sent theirs out. He did not live in a stately house Britney bought him, as her mother did; his addresses were modest. He sought something else. He exerted what Lynne called “absolutely microscopic control” over every detail of Britney’s life. Britney wanted sushi for dinner; she was told sushi was expensive, she had had sushi yesterday. She wanted a pair of Skechers; she was told there wasn’t the budget for it. She was not allowed alcohol, and she was not allowed coffee, and she was not allowed to restain her kitchen cabinets. She was not allowed to drive and was only intermittently allowed a phone, which would, according to some members of a security team hired by Jamie, be surveilled. Close friends were removed from her life.

“My dad isn’t smart enough to even think of a conservatorship,” Britney said later on Instagram, and many people agreed with her; they blamed the company he kept. But it was Jamie to whom the team would turn when Britney was disobedient. It was Jamie who would threaten, should she refuse to work, to prevent her from seeing her children. It was his name on the paperwork that stripped her of autonomy. It was Jamie, drunk on power, who said, “I am Britney Spears.”

Britney returned to work immediately. She released an album. Because she had lost weight and begun working, many people said Jamie had “saved” her. Britney repeated this to the press; her father had saved her. Britney went on tour to 20 cities. “I don’t know, can she rehearse on her birthday?” someone asked an executive who worked for the pastor’s wife. “She’s gonna rehearse” was the response. Jamie hovered. They were shooting a scene in which she kissed a man; she asked her manager to ask him to leave because he made her uncomfortable. When Britney’s trailer was too hot, he duct-taped an air conditioner to a cylinder and piped it in. A “redneck air conditioner,” he called it. “Don’t go nowhere without duct tape.” “Daddy!” she said.

For Jamie, there were threats everywhere. Who wouldn’t want what his daughter had? She was too easily influenced, subject to predators, to men playing mind games. When she found a phone and called the manager, this was evidence that she was still being controlled; Jamie got a restraining order against him. When she covertly tried to hire her own lawyer to get out of the conservatorship, this too was evidence that she was being manipulated; Jamie got a restraining order against the lawyer. It was best if Britney were kept isolated from anyone who might try to, in the words of Jamie’s lawyers, “disrupt the conservatorship,” which was, after all, for her, in her interest, an expression of his love and devotion, a burden he had taken on to save her. His daughter wasn’t well versed in the ways of the world. Much like him, she was inarticulate, trapped within her extraordinary physicality. She couldn’t see through people trying to take what she had. “The best thing for her is what she’s doing right now,” Jamie told the documentarian. “She’s in her element. She’s in her world. Keepin’ her busy. Like me? I like to go fishing. She likes to sing and dance.” Jamie told Lynne their daughter was best treated like a “racehorse.”

A man who had trouble paying his taxes, had declared bankruptcy, had run a small business into the ground now found himself in control of his superstar daughter’s finances. With the money Britney made working at times against her will, her estate paid a lawyer the court had assigned to her hundreds of thousands of dollars a year; this lawyer never informed her, she told the court, that she could petition to end the conservatorship. Jamie’s lawyers fought to keep her inside the conservatorship and charged the hours to Britney’s estate; the estate paid Jamie $6 million, and dozens of different law firms’ fees totaling $30 million. The estate paid her brother; it is unclear for what. The estate paid $1.5 million for repairs and maintenance on her mother’s mansion in Kentwood; the estate paid Jamie Lynn’s husband (also, incredibly, named Jamie) $178,000 for “professional services” to this single house. Jamie decided, around 2015, that he ought to have a cooking show. It would be called Cookin’ Cruzin’ and Chaos With Jamie Spears and would involve a tour bus he retro-fitted and on which he painted a crawfish with a chef’s hat cooking over a cauldron that read KENTWOOD, LOUISIANA. There was never any show. According to Britney, he was drinking again.

Years stretched to a decade of Britney having to barter for dinner. All the youthful delicacy was gone from Jamie’s face; he looked thick-jowled and ragged. A hole appeared in his large intestine, and he spent a month in the hospital. June Austin passed away. Banana, thriving, grew to be 15 feet long. Jamie Lynn’s daughter was riding an ATV while her mother, Jamie Lynn, and her father, Jamie Watson, looked on; she flipped it into a pond, fell unconscious, and nearly died.

Britney refused to do a dance move and was, she said, hospitalized for four months and put on lithium, as Jo Ann had been. Britney did not have regular access to a phone, but she did have an Instagram account mediated by a social-media team; this quirky account was the subject of a podcast hosted by two comedians. A whistleblower, an anonymous paralegal, called in to the podcast and told these comedians that Britney had been forced into a mental-health facility against her will as retaliation for driving and refusing medication. Over time, hundreds of thousands of people became committed to the cause of freeing Britney Spears. “The world don’t have a clue,” Jamie told a journalist. These people were “conspiracy theorists.” Jamie allegedly busted through a door and got into a fight with Britney’s 13-year-old son. The boy’s father was granted a restraining order from the man in control of the boy’s mother.

Her de facto indentured servitude endured for 13 years, at the end of which Britney Spears begged once again to be freed. “I cried on the phone for an hour,” Britney told the judge, “and he loved every minute of it. The control he had over someone as powerful as me — he loved the control to hurt his own daughter, one hundred thousand percent. He loved it.” She thought he and her entire family belonged in prison.

Her family seemed puzzled, bewildered by the suggestion that it might have gone any other way. In the one interview he did, from the home Britney built her mother, Britney’s brother, Bryan, made a joke about how pushy women in his family always get their way. He agreed that perhaps it made sense to end the conservatorship, which had been “a great thing for our family,” but didn’t quite see how things could work with Britney granted the rights of an adult. “Oh, so are you gonna call and make reservations for yourself today?” he asked. “Like, if you’re coming into life and you’ve never had to do something, and having to learn it, it’s going to be an adjustment … everyday-task stuff is probably gonna be a great challenge, like driving,” he said. “She is the worst driver in the world.” The interviewer gently suggested Uber and an executive assistant.

Two people who did not seem confused were Leigh Ann and John Mark, the children June Austin had with Jo Ann. “Typical for this family and how they treat their women,” Leigh Ann told a journalist. “Jamie did to her what my daddy did to my mom and Emma Jean. They are mean and they will destroy you if they can’t control you.”

“These Spears men are something awful,” John Mark told the same journalist. “He ruined Emma Jean and he ruined my mama. He shipped them both off to Mandeville from time to time. So I’m not too surprised about what Jamie’s done to Britney. It’s all about control with the Spears men.” A judge declared the conservatorship ended, and fans popped pink confetti outside the courthouse. A lawyer for Jamie Spears failed to respond to a detailed set of questions from New York Magazine.

A princess freed from a tower is meant to go back to being a princess. Britney, restored to herself, did not do interviews. She stayed on Instagram, apparently unfiltered, where she reached the fans who had finally brought the conservatorship to broader awareness. But it was not the release for which many of them had hoped. She posted endless Reels of herself twirling wildly in yellow ruffles and dark eyeliner. An astonishing number of women told me that after supporting the Free Britney movement, they had regretfully unfollowed her; her posts had become uncomfortable to watch. She seemed unwell. Missing was the control that had turned her into someone we thought we knew: Britney’s unparalleled command of her body, her mastery of self-presentation, that sense that she could become precisely the person she wanted us to see. The connection had been ruptured. The It was gone. This was, in public, unsayable, because it seemed to imply a justification for the conservatorship, but of course social-media posts that provoke unwanted feelings do not justify the abridgment of a woman’s most basic rights. They merely suggest that one cannot be returned to the status of a child for 13 years, placed under the dictatorial control of a damaged man, and emerge unchanged.

A station wagon full of students from Valley Forge, the private white high school, smashed into a parked truck; four of the children died, and the school eventually closed. Collis Temple bought the building that had once housed Kentwood’s Black high school and turned it into a Head Start location, an educational center on the history of Black high schools, and housing for veterans. A local historian discovered there had been a train wreck in Kentwood in 1903 on those tracks that connect the little towns — Osyka, Amite, Kentwood, Tangipahoa — and 75 men had died, some with playing cards still in their hands. Carpenter crews arrived to build coffins and place the bodies in a mass grave. The historian’s name is Antoinette Harrell, and she will tell you with no hint of irony that she is still an outsider here in Kentwood because she is originally from Amite, 20 minutes south, and has lived here for only 17 years.

A place where you can be an outsider for 17 years is a place that keeps its secrets. June Austin “pulled the trigger one way or another” is Leigh Ann’s description of Jean’s death. When I asked a family member what she had heard about June Austin, she said she had only heard he had killed his wife. “Drove her to her death?” I clarified. “No,” she said. “Literally.” But the story that matters here is the story Jamie was told, which is the one everyone was told in the small town where people lived fast and died so often on the little roads winding through the tall trees.

A year has passed since Britney Spears was freed from the control of her father. Lynne, estranged from Britney Jean, lives in the mansion Britney built for her. Jamie, still friendly with his football teammates and most of the town they entertained 50 years ago, chooses to live ten miles away in an RV parked on a vast, perfectly manicured lawn, behind a wooden fence with a gate sign that reads BEWARE OF DOG, four miles from the cemetery where his mother lived and died. Looming over the small RV is a large warehouse, and inside that warehouse are trunks full of stuff belonging to a beautiful woman who resembles no one as much as his mother. Here are the giant shimmering angel wings, here the red ringmaster’s jacket, underwear, the little green top in which she sang about being a slave.

There is no answer to the question of why Jamie Spears effectively imprisoned his daughter for 13 years. If there is, it isn’t here in Osyka, under an ancient moss-furred oak in a graveyard loud with the low buzz of cicadas. Yet it would be hard to conjure a deeper wound than this: not just to be left with an abusive man by a loving mother at the fragile age of 13, but left over her grief for another boy, as if to say, “You, the living son, the eldest son, are not enough.” The opposite of seeking total control over another person is not the establishment of healthy boundaries. The opposite of control is this: a soft wind over a hard stone, a mother present at breakfast gone by dusk, the insistent whisper of that terrible word, abandoned.

More on britney spears

- Britney Spears Moves to Mexico to Escape Paparazzi

- This Is a Movie About a Girl Named Britney

- Halsey Says They Regret Coming Back to Music