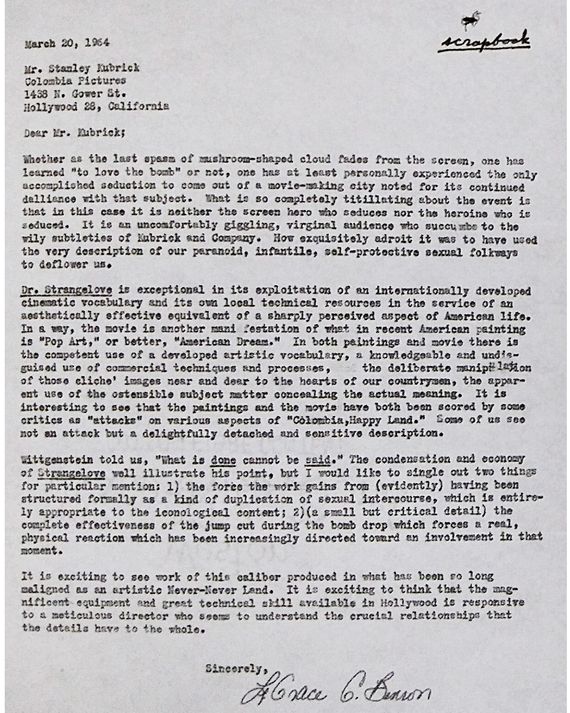

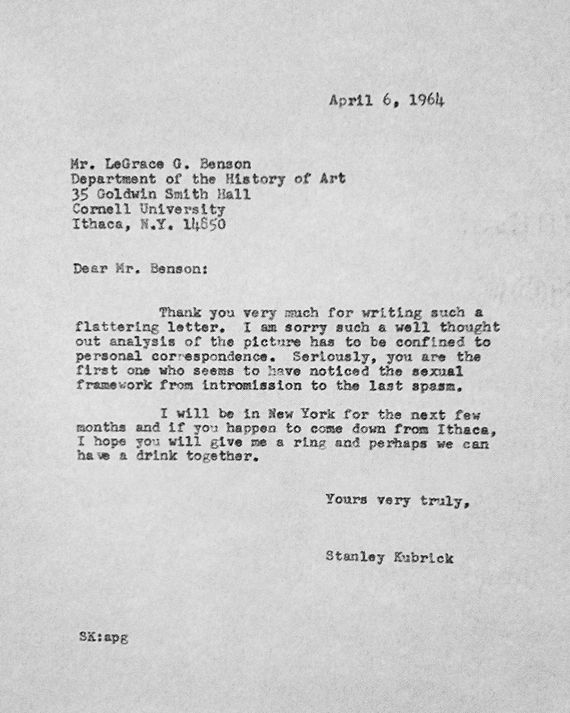

Shortly after the release of Dr. Strangelove in January 1964, Stanley Kubrick found himself back in New York City, where he began working with science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke on what would eventually become 2001: A Space Odyssey. Meanwhile, an associate professor in the art-history department at Cornell named LeGrace Benson had recently started to incorporate cinema into her research and had become determined to learn everything she could about the art form. After seeing Strangelove three times and finding its blend of technical intricacy and scathing satire unshakable, Benson wrote a letter to Kubrick in which she expressed her admiration for the film and shared her theory of how itÔÇÖs formally structured as ÔÇ£a kind of duplication of sexual intercourse.ÔÇØ A few weeks later, she received a response from Kubrick himself, who confirmed her theory by writing, ÔÇ£Seriously, you are the first person who seems to have noticed the sexual framework from intromission to last spasm.ÔÇØ (He also incorrectly assumed she was a man, addressing his letter to a ÔÇ£Mr. Benson.ÔÇØ) His short letter ends with an open invitation for Benson to give him a call if she found herself in New York City at any point over the next few months and wanted to have a drink together.

In 2012, both letters wound up on display in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art as part of a Kubrick exhibit, and images of them have occasionally cropped up on Reddit and Twitter in the years since. After stumbling across the letters earlier this year, I looked Benson up and discovered that, at 92, sheÔÇÖs a working academic active on social media. I sent her an email to see if she ever took Kubrick up on his offer and if she would be willing to speak with me about their interactions. An hour later, she wrote back saying yes ÔÇö she met with Kubrick twice in New York, and sheÔÇÖd be happy to tell me about it.

Where were you in your career when you wrote that letter to Kubrick, and what was your relationship to filmgoing at the time?

This was 1964. I had been an associate professor for a couple of years. I was 34 years old. At the time, we were beginning to bring film studies into the art-history department, where it had been disdained for the earlier part of its history. So I began to look into cinema. The first thing I really looked at seriously was Knife in the Water, which was from a Polish director who turned out to be not such a nice person after all.

I said, ÔÇ£If IÔÇÖm gonna talk about film, I need to do something other than see movies.ÔÇØ I need to do that, but also get in there and find out how to make a film. Not because I was going to be a filmmaker, but because I wanted to understand the process. So thatÔÇÖs what I was doing in 1963ÔÇô64. I took a course in film production, I did some documentary films of artists. I wouldnÔÇÖt want to see them now. But I did begin to understand the differences of someone like Kubrick or Antonioni, who had a firm grasp of the process thatÔÇÖs seamless with their notions of meaning.

I would go to see films. I went to Rochester, where they had a film collection. James Card was in charge of it then. He was great, and they had all kinds of films that they pretended they didnÔÇÖt have. I saw films in the morning, I saw films in the afternoon, I saw films at night. My dreams began to be different ÔÇö they began to have cuts and things, flashbacks. [Laughs.]

So, I was really full of it by the time I saw Strangelove. I sat through it three times before I wrote that letter. That was a time when there was a tremendous interest in the difference between the sexuality of real, ordinary people ÔÇö real life ÔÇö and the prudery of Hollywood. I donÔÇÖt think prudery is a good idea ever. So I forced myself to go even to pornographic films. I couldnÔÇÖt stand them, but I did it. I always took companions with me, so I wouldnÔÇÖt be a female in there all by myself. It was fascinating, and IÔÇÖm glad I did that, but I would never do it again. But that was the background from which I wrote that letter.

If I were to write a letter about Strangelove today, I would want to talk about the sexuality in the movie and its connection to politics. I see it around us all the time right now ÔÇö itÔÇÖs seamless. You canÔÇÖt take them apart. They feed on each other, and I believe I see that in the far right.

I assume that you didnÔÇÖt often write letters to filmmakers. Was this a one-off thing that you did?

I loved movies growing up. I had a Shirley Temple doll, which was replaced with a Princess Elizabeth. I was always interested in films, but this was a special one. I never wrote a fan letter ÔÇö I think that may be the only letter I ever wrote to a star or a director. I guess it reads like a fan letter in a way, but it was an appreciation and a question: ÔÇ£Is this what youÔÇÖre really doing, or am I wrong?ÔÇØ And I was blown away when I received a letter back.

From what I can tell, Kubrick kept almost all of his fan letters, but rarely responded, and almost never engaged with questions about the meanings of his films. But with your theory about Strangelove, he seems to have been immediately drawn to it. After you received that letter, how did your meeting with him come about?

We had two meetings. I went to New York City to visit all the museums and keep up with everything that was happening. I went down there, and I really was apprehensive about meeting this great director. Whenever I go to New York and I feel a little uneasy, I go to the Met. So I went there, and I stayed there for a few minutes in the lobby until I calmed down. Then I went to the public telephone and dialed the number.

A voice said, ÔÇ£Talk!ÔÇØ Which put me off a little bit, but because I had made some films, I knew thatÔÇÖs what you say when you want the sound to start. So I told my name, and said IÔÇÖd received the letter and that IÔÇÖd like to speak to Director Kubrick. Next thing I know, Kubrick was on the phone. No delay, no ÔÇ£call back later,ÔÇØ or anything.

Everybody was surprised there was a female professor. This was ÔÇÖ64. They had thought I was a guy, so he was a little surprised about that, but he said we could meet tomorrow at a restaurant downtown. I said IÔÇÖd be there, and I think we were there for two and a half hours, talking about film and Strangelove. Then he said, ÔÇ£IÔÇÖd like to continue this conversation tomorrow morning, if youÔÇÖre available for coffee at ten oÔÇÖclock.ÔÇØ And of course, I was, no matter what else I had going on. By the way, he was very reassuring. He was quiet, and he seemed genuinely interested in what I had to say.

While we were walking together before coffee, he said, ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm making a film about outer space and aliens. What do you think aliens look like?ÔÇØ I have never forgotten that question, because I had never thought about what aliens look like. The question just sat in my mind, and recently I thought, Now I know the answer to the question. Too bad Stanley KubrickÔÇÖs not here to hear it.

Is the answer a giant floating baby?

No! Boy, was that pure Kubrick. Now, with the studies IÔÇÖve done in ecology I would say that an alien from outer space would be related to the ecology of whatever planet it had been on. But that was a startling question, to which I had no answer whatsoever. I felt so dumb, but he didnÔÇÖt treat my response that way at all. We kept on talking about what would become 2001. For me, that was one of the high points of my research history. I appreciated his respect for my letter and for my ideas. And he said one thing that I do want to tell you: He said, ÔÇ£You know, I didnÔÇÖt even really go to college. And IÔÇÖve always been a little bit in awe of people who are professors and have gone to college.ÔÇØ

I was sad about that, because my notion of knowledge and skill is that everybody has a lot of it, and somebody who makes a really good film has a knowledge and a kind of intricacy ÔÇö a depth of knowledge. No professor could make a film like that. And I let him know that. That was my response: This is rich, deep, thorough, useful knowledge that you have that no professor has.

Was he able to take that compliment?

I think so. He was a little surprised, but I think he liked hearing it. He was deferential about it, but I hope he appreciated it, because itÔÇÖs true. People who can make things and do things have a huge amount of personal knowledge, as it was called by a philosopher called Polanyi. He said you couldnÔÇÖt conduct science without personal knowledge, and you sure canÔÇÖt make a movie without it.

I know Kubrick read somewhat voraciously. Did you talk about philosophy and literature, to any degree, or mainly his movies?

We talked mostly about the movies, but in our conversation I became aware that he also had a lot of book-larninÔÇÖ.

A lot of what?

Oh, I used a southernism. Book-larninÔÇÖ. Book learning. We call it ÔÇ£book-larninÔÇÖ,ÔÇØ down where I come from.

And where is that?

I was born in Richmond, but my father was a jazz musician and we lived in New York City for a good part of my early childhood. When I started school, we were in North Carolina, where family was. ThatÔÇÖs where I grew up and went to college.

You mentioned that Kubrick had assumed you were a man, and I wondered if he hadnÔÇÖt come across the name ÔÇ£LeGraceÔÇØ before.

He probably had not. ItÔÇÖs not unheard of ÔÇö there are other people with that name. But itÔÇÖs not frequent, and many people who havenÔÇÖt met me think IÔÇÖm a man.

How did you feel about 2001 when you saw it?

I loved the movie. I liked the opening sound of it ÔÇö the music. I liked everything about it. Of course, I was kind of set to like it, but I always try to keep that sort of thing in check, and say, ÔÇ£Okay, letÔÇÖs be critical.ÔÇØ I saw it three times.

IÔÇÖm sure it was difficult to remain objective after speaking with him.┬á

ThatÔÇÖs true. I had heard enough about it that I was all set to like it. Besides that, let me tell you that, as a child of the ÔÇÖ30s, one of my favorite cartoons was Flash Gordon. You may not even know what that is. It was a comic strip, which you hardly ever see these days, but this was the ÔÇÖ30s, and Flash Gordon was out in space and doing things that Kubrick would eventually have in his movie.

Is that something that you mentioned to Kubrick, or were you like, Maybe I shouldnÔÇÖt mention Flash Gordon to this esteemed film director?

You know, I donÔÇÖt know if I mentioned it or not. I probably did in passing. I had enough good sense not to ask, ÔÇ£Oh, did you ever read Flash Gordon comics?ÔÇØ I know I didnÔÇÖt ask that question. Maybe that was a missed opportunity.

WhatÔÇÖs your relationship to his work been in the years since? Did you keep up with his movies, and is Strangelove still your favorite?

I donÔÇÖt want to be too complex about this or go into it too much, but I saw some French film, I think by Chabrol, that was so violent, and I was so deeply struck by it, that I stopped going to the movies at all for several years. I have never quite taken it back up ÔÇö I do go to movies now, but I set that aside.

I have seen some clips of recent movies, and I donÔÇÖt see any compelling reason to go back to most of them. TheyÔÇÖre thin! I would go to a funny one, but the romantic ones arenÔÇÖt even about real romance. TheyÔÇÖre not about real peopleÔÇÖs romances, or seldom are.

Were you aware at the time that your letter ended up in a museum exhibit?

I did not know that until later. I was out in L.A., giving some kind of presentation, and thought, Well, letÔÇÖs go to LACMA. And there was my letter! I was really surprised, and of course I was pleased. The letter from Kubrick and our conversations were always a treasure, and I just never expected to hear anything about it again.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.