Myrlande Constant learned to sew with her mother, whom she later worked alongside in a Haitian wedding-dress factory in the late 1980s. She soon started making her own versions of Haitian flags, or drapo, expanding her art with embroidery and beading. With roots in West Africa, brought to Haiti by enslaved people, drapo are decorated in sequins and usually depict tribal, ethnic, military, or religious symbols. Usually, they are made by men. A woman making drapo while combining her own imagery with a pantheon of Haitian mythology strikes me as revolutionary. “I work every day, as long as I can,” Constant says. “Child, I am so loaded inside.” I’ll say.

Four showstoppers of the ten works on display at Fort Gansevoort gallery power the New York debut of this 54-year old visionary. These meticulously wrought embroideries involve Constant applying a drawing or cartoon on one side of a piece of fabric. The cloth is stretched and set on supports, with the drawing facing up, as Constant, her children, and an atelier of assistants gather on all four sides and string beads and sequins onto the material. They use a tambour stitch, in which the cloth is pierced by a needle that is then strung with a single bead or sequin on the underside. The image, in other words, is formed out of the maker’s sight, backward, then flipped over. It’s like film photography in this way: A negative image is developed into a positive one.

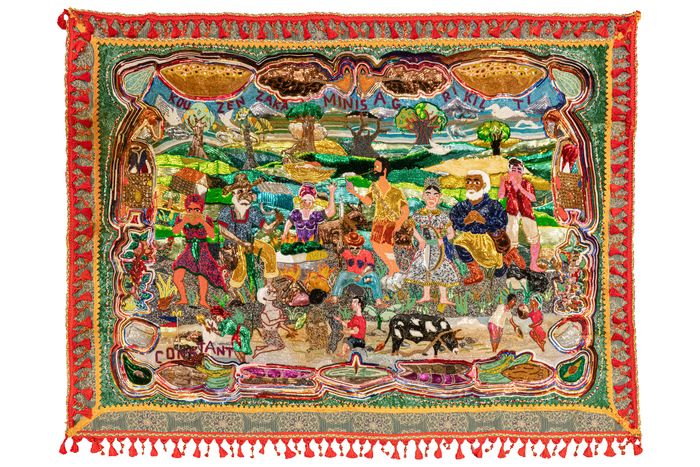

The effect is thrilling. The surfaces have the feel of crusts, scales, feathers. They are reminiscent of both enameled cloisonné and gold-leaf-illuminated manuscripts. There is a glut of detail, such that just as images begin to form, they break down and reform. You feel a spirit inhabiting these magic-carpet-like objects.

The first floor of this too-little-known gallery in the Meatpacking District features smaller images of what look like Madonna and Child, spirits, Saint Patrick and other saints. A lexicon of reverie and reverence is being presented, an idea of sacred and profane forms.

The large masterpieces in the upper two rooms mushroom into psychological and spatial multitudes. Constant is working at the scale of the Mexican muralists while echoing something of Chris Ofili’s early dazzling dotted paintings with elephant dung attached. You look at Constant’s work all at once and also millimeter by millimeter, bead by bead. The maniacal density of visual information is transporting.

The surfaces speak. The angle of a sequin can create an arching eyebrow, a sly smile, or a flaring nostril. Each bead has a different reflection depending on what angle it is attached to the surface. Things glimmer then come into focus: You make out craggy rocks, flowers in gardens, water flowing. Mythical scenes form as if spoken to life from some ancient oratory.

Constant presents a teeming yet cohesive cosmos. The large works give us humans communing with lwa (spirits), scenes of Haitian Vodou, the sacrifice of animals. It’s like peering into a kaleidoscopic world where the dead are side by side with the living. There are skeletons, coffins, what looks like a healer spraying liquid from her mouth onto a patient. Here is an atmosphere of ritual, magic, and folk wisdom — talismans, treatments, and prophecies.

Look at just one large work, Reincarnation des Morts. The title is embroidered in red and blue beads along the top, while the border is purple, black, and white — colors associated with the spirits depicted. The scene is a graveyard. There’s a winged skeleton sitting over the figures of Bawon Sanmdi, the guardian of cemeteries, who links arms with Bawon’s wife, Manman Brijit. Their faces are half flesh, half bone. She wears a marvelous tilted black hat and holds a lighted candle. He holds a bottle and offers a mug to a little white-shrouded figure of bones nearby. A magnificent spotted red serpent slithers up a tree. This is Damballah, the primordial creator of life in Haitian Vodou folklore. The whole scene is surrounded with pickaxes, shovels, and the remains of the dead.

But as with Tibetan mandalas or Navajo sand paintings, you don’t have to know what any of these things mean in order to understand that you’re in the presence of pictorial magnificence. Constant’s art has incantatory grandeur, and it deserves to be on the walls of major museums.