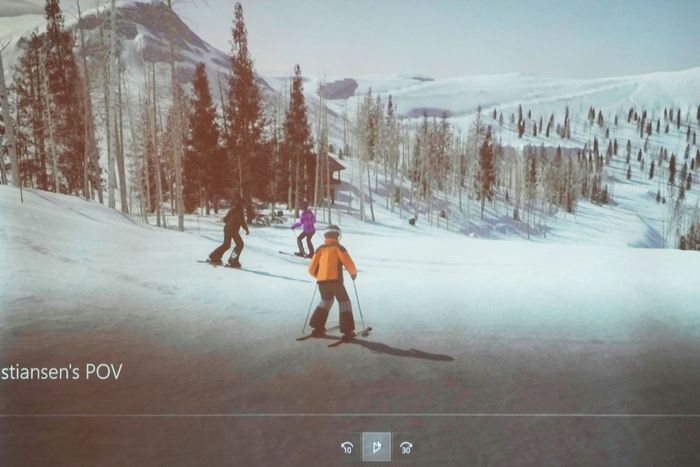

We, the rapt collective of people still subsisting on Gwyneth Paltrow’s ski-crash trial, still need to be fed every last detail about the legal event of the century. Luckily for us, Brian Brill, Paltrow’s forensic ski animator, has thrown us a bone. Brill spoke with Vulture over the phone about the animations he and his Colorado-based team at Mountain Graphix created for Paltrow’s defense, detailing the data-driven process behind the Sims-quality, courtroom-admissible VFX. “I don’t know her, but I’ve always enjoyed her movies, so I think she seemed very nice,” he said of Paltrow.

Brill, himself a former ski patroller, worked with Dr. Irving Scher — remember the biomedical engineer who taught us math and drew a lap-dancing force diagram? — and other experts to depict what happened on that fateful day, when plaintiff Terry Sanderson and Goop’s mother collided on the Bandana run at Deer Valley Resort. “Well, I lost half a day of skiing,” Paltrow famously testified in the case during which she was ultimately found Gwynnocent and awarded $1 in damages from her countersuit. Could Brill have animated the rest of her ski-less day? “Yeah, I definitely could have,” he said. “That would’ve been a lot more fun.”

Could you give us a little insight on the company and your background in animation?

I’ve always really enjoyed programming computers back in high school and then went to college for it — got a master’s in computer science. But then I really enjoyed skiing, so I started living at a ski area, doing all the ski-area stuff. I thought I was never really gonna do anything with the computer-science degree. But then all of a sudden, my boss came over and he said, “Something’s broken with my computer. It’s only typing in capital letters.” So I would go over and push the caps-lock key and then they would go, like, “Ooh, computer-genius guy.” I was a ski patroller, and when you’re a ski patroller, different people have different specialties, whether it be avalanche control or chairlift evacuation. They needed somebody who would be an accident-investigation person, and I wound up kind of falling into that.

When an accident — like, a real accident — occurred, we would typically just start by drawing a map and then drawing little symbols and measurements on it. But for ski patrollers, they’re outside in the snow most of the day. Your hands are frozen and the maps look bad, so I started applying my degree. It just made it easier, and it made it look a little more professional. Then I started learning about the field of GIS, which is geographic information systems — basically computerized choreography.

When was this?

These were the days before Google Earth. Little by little, I was asked to show what I can do, as far as mapping and documenting accident sites, at different conferences around the country.

Lawyers started coming up and going, “Hey, you know, I’ve got a case. I really just want to help educate the jury. This accident happened, and this is a really nice way to show it.” And instead of it just being a cartoon or something made up, it was based on GPS at the time, and then lidar, and then surveys and any kind of geographic information that we had. I would incorporate that as the foundation for the backdrop. The coolest thing about it is that technology is getting better all the time. Part of it is to kind of find a quicker way to do this, or to make it look a little better, which actually can sometimes be a little bit of a downfall for us. What we usually want to do is just make things really photorealistic, but then attorneys will frequently ask us to back off on that and make it more stylized.

When I think of the images I saw during the Paltrow trial, I think of that silly-looking force diagram the biomedical engineer drew — with the stick figures sitting on top of each other — juxtaposed with your sleek, professional animations.

They purposefully said, “We don’t wanna show the body motions.” That’s something we would’ve been very happy to do, but you run into people having more that they can object to, like, “Oh, my wrist didn’t move like that” or “My skis are closer.” So for this one, we were, for the most part, just showing the location of the skiers, as told to us by [ski instructor] Eric Christiansen, Paltrow, and the experts. They wanted to focus on the — not motion of the bodies but just the location of the bodies and the relative speeds to each other.

Do you keep models on hand for something like this, or did you start from scratch for this trial?

There’s two steps to it. The first is the data collection and getting the scene. I need to separate that into two parts because one of ’em, I mean, it’s as accurate as you can get.

I’ve got this 3-D laser scanner …

What does the 3-D scanner do?

It’s the coolest tool. You set it up on a tripod and it will shoot out a little pulse of electricity, comes back — and then you have what that distance is. It does it like 11 million times in five minutes. It creates a three-dimensional model that’s accurate down to millimeters. And then you’ve got that 3-D model. That’s the foundation. What I love about this is you can’t argue about it — it’s just the data. And we made sure to visit the site, you know?

It would’ve been great if we were able to be there that day.

Well, Terry Sanderson’s lawyer said that he was still spiritually on the trail.

I don’t know what parts — whatever parts of Terry are still on the trail. I hope they put some bamboo up and block it off.

We try to do everything that we possibly can. We find out where the sun is for that day of that year [so] we can get the lighting, what the shadows were doing, at that time. We really try to go do everything we can to make it as true to what it was.

How did you get everyone’s descriptions of what happened that day?

I never met Gwyneth Paltrow or Eric Christiansen, but I was working with Paltrow’s legal team remotely. We created scenes based on hearings and depositions and then the attorneys would take the rough draft to the ski instructors, Ms. Paltrow, and everybody else. And then we’d get a bunch of notes and then we’d change it. So there were a number of different iterations for this.

When did her team reach out to you, and how long were you working on this project?

In 2019. They reached out to me, but then nothing happened for a year or two. It was about two years ago — five years from the day of the accident —where I went out there and spent the day taking 17 different scans, basically scanning the entire trail. That’s like half a billion data points.

Did you form an opinion on what happened that day after you animated it?

I’m what you call a non-opinion witness. I had no opinion. It was my job to survey the area and create the landscape as accurately as it was so nonskiers can understand what a ski trail looks like.

When you were in the process of doing your research, did you or your team ski the Bandana run?

Oh, I did. I actually skied it.

What was it like?

It’s just a very simple green run. It’s a perfect trail to take your children and your boyfriend’s children to go down. There’s nothing wrong with the trail at all.

I’m not a skier. My mom tried to make me do ski club in middle school, but I refused because I hate winter. So I’m trying to imagine in my brain what an intermediate skier like Paltrow would think about this hill. Is this run challenging at all?

Oh, no, no, no, no.

It’s an easy run?

It’s a very simple run. That’s part of what we wanted to show people.

Did you create alternate models where Paltrow was at fault?

I actually worked for weeks with Dr. Scher, where we tried to make [witness and friend of Sanderson’s] Craig Ramon’s description of what happened work. With skis, there’s a good amount of ski in the front, but there’s also a good foot and a half of ski behind your foot. And Mr. Ramon’s description — he’s saying that the tips kind of spread out.

Well, if the tips are spreading out, the tails, the backside of the ski, are going inward, you know? And that actually would’ve captured Ms. Paltrow. And there’s no way that she would’ve been able to go forward from there. We tried hundreds of different setups and possibilities. “What if this foot was over there? What if this is over there?” There is not one way that we can [make it work]. It just can’t.

What programs do you use? Is it like The Sims?

Have you ever seen the movie The Matrix and you just had the screen with the green dots and green letters coming down the screen? Well, it’s not like that. It doesn’t look as polished on my side before rendering. It’s kind of like everything’s been wrapped with graph paper in a way.

Did you ever play The Sims at all?

No, but now you make me think that I should! Our computer setups are pretty extensive. We have a room of computers that we call a render farm. At first, everything starts off in GIS, [and] I collect a bunch of 3-D scans of the actual location. That data and information is brought into a program called Scene by a company called Faro. Once that data is processed, we incorporate that data into the GIS software. Then we’ll take all of that GIS data and then we’ll bring it into a program called 3ds Max. And then we can start animating characters and choosing the virtual camera locations. Does that sound too pretentious?

No, it sounds cool!

It would be fun to work for Pixar: “Oh, okay, I want my monster to work like this” or “We’re at, like, the whatever fictional landscape.” But for this, you need to be able to be deposed and explain the accuracy of everything. That takes a little bit of the fun away from it, but that allows it to be admissible in court. Our animations are different than the cool Iron Man animations. I just thought Ms. Paltrow would see this and go, “No, no, no, no.”

Well, she’s actually known for not remembering the movies she’s in. She doesn’t even remember appearing in Iron Man.

[Laughs.] That’s really funny. I’m just glad she wasn’t unhappy with the animation.

Were there any little Easter eggs in the animations?

Unfortunately, no. When we started out, me and my main colleague, Darrell Dingerson, we were like, “Hey, let’s try to put, like, a little palm tree to hide in each of our little scenes.” But no — doing this for litigation purposes takes some of the fun out of it.

Could you have modeled what Gwyneth Paltrow’s half-day loss of skiing looked like with your software? Could you have modeled the cabin and/or the resort and the hot tub or whatever she did during her lost half-day of skiing?

Yeah, I definitely could have. That would’ve been a lot more fun.

Is there a way you could upload it online and we could all do the Bandana run in virtual reality?

The model’s already made. That gives me something to think about. Thank you very much for that.

Oh, wait — I almost forgot! I wanted to know how much something like this costs.

Oh, I don’t know. [Laughs.] I think we have a bad connection! [Laughs.]