Watching Sweeney Todd at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre, you’d be forgiven for assuming you made a wrong turn and ended up at an abandoned industrial dockyard. Mimi Lien’s set for the revival of Stephen Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler’s musical resembles a cast-iron bridge connected to a tower topped with an imposing crane. Soon, you’ll see the top level of the construction stand in for Sweeney’s barbershop and discover that he’ll dispose of his victims’ bodies in the basement of Mrs. Lovett’s pie shop by dropping them down a chute hidden at the back of the set. The crane, meanwhile, will also deliver that crucial other star of the show: Sweeney’s barber chair. It’s all very grand — and very sinister.

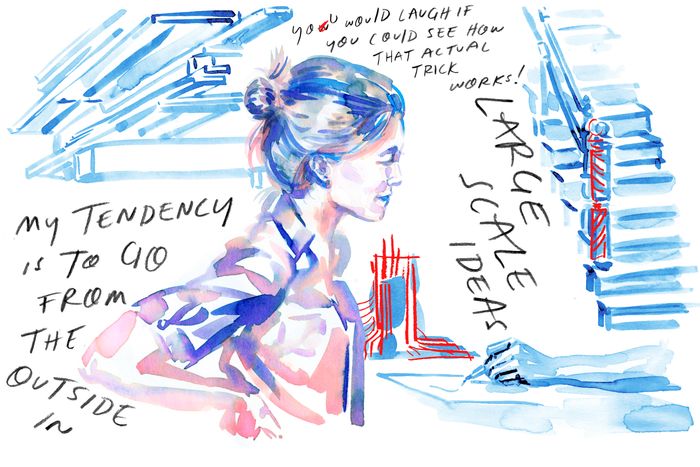

“I’ve always had large-scale ideas,” Lien says from her studio. “I just finally arrived in a place where I can do what is my natural tendency.” Lien originally studied architecture in college but has made a career — and won a MacArthur grant along the way — in scenic design for theater, opera, dance, and other forms of live performance. You may be familiar with her work Off Broadway in the profusion of cotton balls that fell onstage during An Octoroon; on Broadway in the scaled-up supper-club set of The Great Comet; or just nearby Broadway in her installation The Green, which transformed Lincoln Center with a synthetic lawn for the summer of 2021. Even when it wasn’t large scale, her work has always tended toward an enveloping quality. “I’m interested in what the largest container is for the piece, including the audience,” she says. “My tendency is to go from the outside in.”

Given that tendency, it’s fitting that Lien’s latest Broadway project has involved placing the audience in the midst of dark and stormy Industrial Revolution London in Sweeney Todd, directed by Hamilton’s Thomas Kail. The musical, about a demonic barber and his baker accomplice, Mrs. Lovett, is beloved in the theater world for its rich score and high drama — Sweeney and Lovett’s plan involves slitting the throats of his customers and then baking their bodies into pies — and was first staged on Broadway in 1970 by director Hal Prince with a famously elaborate set by Eugene Lee. More recent productions since then, such as John Doyle’s version or a pie-shop-based immersive take Off Broadway, tended to shrink down the musical. The challenge for Lien this time around was to go big again — and yet not just re-create the original.

Before Kail approached her about doing Sweeney, she had only ever seen Doyle’s version of the musical and wasn’t especially familiar with Kail’s production history. “I consider myself an outsider to theater, until after I had finished college,” she says. “So I have none of the baggage of high-school productions or growing up with musicals.” She avoided looking further into Lee’s designs and instead decided to focus on what came out of studying the score and libretto of the musical, as if she were designing for an opera. Her inspiration came right out of the musical’s lyrics, specifically when Sweeney describes London as “a hole in the world like a great black pit.” She points to the line taped to the wall above her desk. “That was the world I wanted to create,” she says. “For me, the container of the show was the city of London — everything that it represented at the time of the Industrial Revolution.” Knowing the specs of the Lunt-Fontanne, she was also aware that it had a tall proscenium and that she would have access to a trapdoor, which is used a few times in the production. “I wanted to feel like we’re going into a subterranean space,” Lien says. “A lot of the research I was looking at was about the sewers of London because the invention of the sewer happened during the Industrial Revolution and allowed the megalopolis of the city to exist.”

Lien first joined the production in February 2022, about a year before the musical began loading sets into the theater. From there, she started on a few months of research before modeling designs in her studio. “I don’t do a lot of renderings,” she says. “I do very rough sketches until I know enough to build something and put it into a model and then I do multiple iterations of a model. Maybe that comes from my architecture background.” Working with scale models allows her to easily move around elements of a set she’s considering and helps her understand the real proportions of a piece (“Models don’t lie,” as she puts it). In this case, she started in on rough models last May and arrived at a final design toward the end of the summer.

Lien’s design, built out of that study on Industrial-era London, ended up involving a bridgelike upper level over Mrs. Lovett’s pie shop with the ability for the piece to rise further on the stage and bring the audience down to her oven in the basement. Lien also knew she had to design a barber’s chair attached to a chute that would allow Sweeney to dispose of the bodies, “so from the get-go, it felt like levels were going to be a thing,” she says. The music also instructs you as to how Sweeney puts together his plan step-by-step: First he gets his razor back and then gets his barber chair, in which he slits his victim’s throats and then reclines the chair so that their bodies slide down a chute for Lovett to retrieve and bake into pies. Lien wanted the entrance of Sweeney’s chair to be a grand moment in and of itself, so she decided to have it arrive in a box suspended from that gantry crane that hangs over the set, like a shipping delivery. “The crane felt like a mechanism that would establish the industrial milieu but have practical functions,” Lien says. “The jib arm of the crane is actually supposed to be somewhat knifelike, a menacing presence always hanging above the show.”

Lien brought that concept to the producers in August before they went into a budgeting-and-revision process. Kail pushed her to pare down the design primarily for storytelling reasons. They ended up cutting two other bridgelike pieces of the set to focus on one main bridge piece. “He really wants to essentialize,” she says, “and it always feels good to pare down to what you only really need, even if it’s not budget-driven.”

Once she had his and the producers’ approval, she brought the designs to the engineers at the Hudson Scenic fabrication studio to start building the set out of steel, though she wanted to stick to design principles that would make it resemble 1800s cast-iron construction (cast iron, for instance, has less tensile strength than steel; Lien had a lot of back-and-forth with engineers about this set’s hinges). Once the steel (but cast-iron-esque) set started being loaded into the theater this winter, the production went into tech rehearsals and refined the look of the show. There, a crucial element in conjuring a “great black pit” was also the lighting, designed by Natasha Katz. “We had a close collaboration from the beginning,” Lien says. “With a lot of this industrial architecture with open-truss work, that stuff is built for shadows and light sources coming through.” The show is designed to have a few scares in which characters emerge from and disappear into the shadows — at one point, Sweeney and Lovett seem as if they disappear into the stage. Lien, for all of this discussion of grand large-scale design, points out that that exit is built around a very old-fashioned theater design. “We did a lot of lo-fi theatrical effects with sleight of hand and misdirection and shadows,” she says. “You would laugh if you could see how that actual trick works!”