It’s one thing to talk for 100 minutes, and another much more significant accomplishment to stay in the moment for all that time, to seem to be thinking in character as you recite all those words. Jodie Comer, alone onstage as a hotshot barrister in Prima Facie, almost never stops talking. She may as well be delivering one long run-on sentence, telling a story that kicks off with post-court-appearance braggadocio and then burrows back into her own experience of assault, full of British legal terms, then suppressed memories, then fury. Comer’s performance moves at the relentless pace of someone trying to outspeed her own pain, and she’s up there keeping pace with a character whose mind moves at Mach 10. It’s an incredible breakneck feat, in which Comer achieves escape velocity from the script of Suzie Miller’s unsteady play and exerts a thrilling and devastating gravitational force of her own.

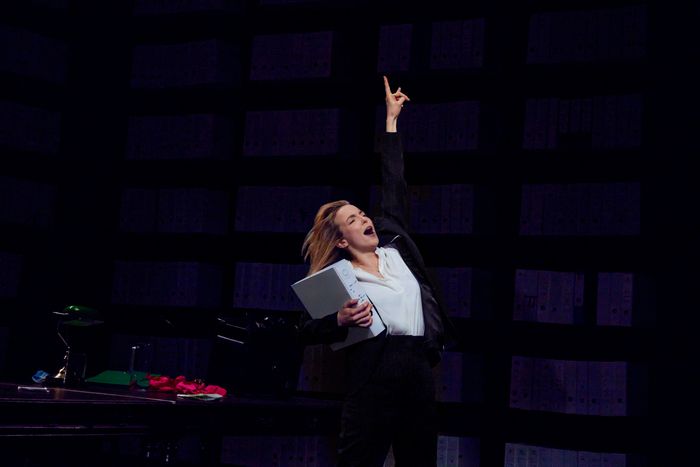

That Comer is able to pull all that off is both expected, given the facility she’s shown on film and television, and a mild surprise, with her lack of experience onstage. At 30, she’s best known as Killing Eve’s chic assassin Villanelle (though I’d also argue for the depth of her performance in the overlooked The Last Duel), but before all that acclaim, she found it difficult to break into British theater—according to a New Yorker profile, she received a class-coded message that she wasn’t educated or trained enough. The dynamic of someone holding her own in a hostile environment charges this performance. Prima Facie, when she started performing it in London last year, was Comer’s first stage role. (This spring, she won an Olivier award.) Like her character, Tessa, Comer is from Liverpool, and she uses her own Scouse accent. She’s got an intuitive handle on this striver by way of Cambridge whose mother still cleans offices and buys her gaudy shirts to wear in court. Separately, she has also quickly mastered the physical modulation of stage work. Comer may be accustomed to close-ups—and she expresses emotion with the arch of her brows in a scene where Tessa is recorded on video at a police station—but knows to speak with her whole body. She begins with the stiff deportment of a woman codeswitching to fit in (and donning a horsehair wig), then gives over to the world-eating swagger of someone who excels and knows it, all before she starts to crumple.

Miller’s play provides Comer with straightforward but potent material. Trained as a lawyer herself, she structures the play like an argument. At the top, there’s the case for the law as it is. Tessa, eager to prove herself as a criminal-defense barrister in London, has taken on a series of cases related to sexual assault and developed a knack for getting her male clients off the hook. She believes firmly in the system, and rationalizes that it’s the prosecution’s failing, not hers, if a guilty man isn’t punished. She has a way of picking apart the testimony on the stand—Comer shows us how by pacing the room, a microphone close to her mouth, being poisonously sweet to an unseen witness. Then those rationalizations turn against Tessa, when she spends a night drinking with another barrister and he rapes her. Miller arranges a situation that’s grimly and believably difficult for Tessa to argue around in court: they were drunk; the two of them had sex consensually in the past; witnesses would have seen them flirting earlier. But Tessa pursues her case anyway, driven to exact whatever justice she can.

Tessa’s experience is gutting, even though Miller, as she brings things to a conclusion, falls back on the didactic. In the latter third of the play, as Tessa’s case unfolds, Miller writes her speeches that take the law to task, and they play well to an audience but become broad and vague. “The system feels faulty and mixed up,” goes one such line, “The legal system feels broken.” The fact that there needs to be a better way of handling cases of sexual assault is undeniably true—yet the play, for all its anger at that system as it stands, doesn’t pursue its assertions further, into potentially less widely palatable territory. (How to Defend Yourself, recently, has proven there’s much more to explore there.) Miller’s writing also retains an inchoate carceral impulse—Tessa, for instance, develops affection for a young female police officer in the court—that goes underexamined alongside her imagining a better way. Justin Martin’s direction hammers on the material, too, double-underlining what Comer’s performance already makes clear. The play has a neon-framed set by Miriam Buether (someone needs to separate British productions from their noble gases) that pulses with light during Tessa’s more significant realizations, as well as a electronic pop score by Self Esteem that’s meant to quicken your heartbeat with tension but ends up distracting. Prima Facie’s final moments, which in an ideal world would stay with Comer, are given instead to music and lighting effects.

If the writing and production falter, Comer’s performance speaks more than clearly than all that’s going on around her. She locates, in Tessa’s disappointment, the resentment of someone cutting herself on a knife she thought she knew how to wield expertly. Comer emphasizes what makes Tessa specific—her humor, her chip on her shoulder, her fraught connection with her mother—even while Miller’s writing gets more generalized. She tries to make the character into not an everywoman but an individual who’s clinging to whatever she can to try to balance her reality. That gives Prima Facie its overwhelming emotional heft. Arguments may be convincing in the abstract. But it’s in staying with a singular case, making you feel for a wholly realized person, that Comer articulates what’s real, urgent, and unbearable.

Prima Facie is at the John Golden Theatre.