If history is written by the victors, it’s being rewritten — still by the victors — in The Thanksgiving Play. In Larissa FastHorse’s satire, a group of liberal-minded white people gathers to devise a play about Thanksgiving that will honor a Native American perspective on the atrocities Pilgrims committed without any insight into an actual Native American perspective. Their project, as you’d expect, goes wrong quickly. The problem is that The Thanksgiving Play intentionally hurtles its characters toward a dead end — like Wile E. Coyote toward a tunnel entrance that’s just drawn on the side of a rock — and it gets stuck once they crash. It takes them down but never justifies why we’re here with them in the first place.

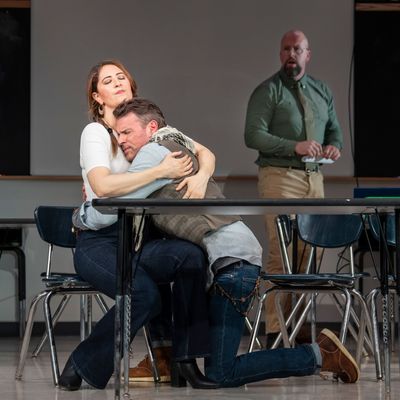

The entire play takes place in a high-school classroom, where Katie Finneran’s crunchy drama teacher, Logan, has taken it upon herself to come up with an appropriately sensitive play for Native American Heritage Month. She’s got justice on her mind — as well as grant money and career redemption after she staged a production of The Iceman Cometh that did not go over well with parents. (Riccardo Hernández’s set has flyers for a series of inappropriate high-school productions pinned to one wall — amusingly and horrifyingly including How I Learned to Drive.) Logan is a caricature of a tone-deaf white woman, though Finneran — always a capable comedian and delivering a very funny overpronounced version of “al-lies” — tries to ground her with a pinched neurosis. Logan’s lover-collaborator, Jaxton, is played by Scott Foley as if his Felicity character, Noel, had taken a left turn into a yoga obsession but retained his slightly smarmy nice-guy core. Rounding out the group, Chris Sullivan plays a history teacher with dreams of the stage (and a selfie of himself with Lin-Manuel Miranda on his desktop), who has prepared reams of research on colonial history that no one wants to pay much attention to. FastHorse writes volleys of jokes about this trio’s general obliviousness, though they’re such easy targets that they basically just stand onstage inertly being pilloried. Foley arrives holding a mason jar. Finneran can’t stop saying nonsense about how devised theater works. Sullivan is hung up on literally versus figuratively.

Quickly, D’Arcy Carden arrives to mix things up as an airhead actress named Alicia. Logan has hired her to lend a legitimate Native American perspective on the project. It’s no spoiler (because you figure it out almost immediately) to tell you that she has been faking her background to land roles. But until the rest of the characters wise up, they tiptoe around her, trying to make space for her thoughts, which include musings about how much she likes NFL games and Disney movies. Carden, making her Broadway debut after rising to fame as The Good Place’s “not a robot,” is gifted at physical comedy and able to find a range of funny beats in the way she absentmindedly sips a Frappuccino, but once the jig is up, she has nowhere to go in the role. All of the characters have to sit around admitting that they don’t know what they’re talking about — and they’re just not interesting as actual people. Carden and Finneran split off for a scene in which Alicia advises Logan on how to look less frumpy and get Jaxton’s attention again, but because FastHorse doesn’t invest too much in these women’s depth, the actresses are at sea trying to make their dynamic real and human.

The comedy is best when it leans bleaker. (These people are already paper-thin, so why not set them on fire?) The two men come back onstage after Alicia and Logan’s moment to demonstrate their historically informed idea to have a scene in which Pilgrims throw around the severed heads of Native Americans for sport — complete with prop heads that ooze blood. The idea defies logic (where did they get these heads so quickly?), but it’s so gruesome that it’s compelling. The rest of the play carries on with prop blood splattered across the stage, which is at least upsetting on a tactile level.

The sharpest critique that comes with The Thanksgiving Play, however, is its production history. FastHorse, a member of the Sicangu Lakota Nation, has talked about writing a play for a white cast (in the script, she specifies that BIPOC who can pass as white may be considered for the roles) so that it would be widely produced. (She has had trouble getting theaters to produce plays that require Native American actors.) On that point, she succeeded. The Thanksgiving Play had a run Off Broadway in 2018, was one of most produced plays in the U.S. in the 2019–20 season, and has now come to Broadway. Putting it on allows Second Stage to feature work from a Native American writer while still able to fill the cast with recognizable TV stars. It’s a move that flatters an audience — especially if a lot of the people in the crowd are white nonprofit-theater subscribers who resemble the characters onstage, because even if it’s making fun of them, they’re still at the center of the story talking about how they shouldn’t be at the center of the story. In that way, it reminded me of the tonal swerve of The Minutes, which itself tried to tackle the U.S.’s history of genocide with a set of characters who weren’t Native American and ran into a similar wall. When you take that angle, you can bring everyone to the moral abyss, but then nothingness just stares back at them.

This version of The Thanksgiving Play, however, gestures toward a way out. Between scenes, FastHorse and director Rachel Chavkin (who helped explore a richer mire of messy progressivism in How to Defend Yourself) have filmed and inserted videos of imagined school projects about Thanksgiving, starting with very young kids doing an offensive counting song in stereotypical outfits and aging up from there — each iteration gaining a bit more sensitivity. One of the later videos has a band of Indigenous middle-school kids singing a punk song that mashes together and sends up “Home on the Range” and “My Country ’Tis of Thee” with infectious anger and enthusiasm. There, you get a sense of what the rest of this play is missing — the subjectivity of actual Indigenous people and children (both of which characters onstage only talk about in the abstract) — and a heart. FastHorse and Chavkin have real affection for these kids. You wish the play had been handed over to them instead of to the bumbling adults.

The Thanksgiving Play is at the Hayes Theater.