There is no passivity in Contempt. Jean-Luc Godard’s film about the unraveling relationship between a renowned playwright turned screenwriter (Michel Piccoli) and his wife (Brigitte Bardot) asks audiences for active viewing from the outset, to shift the gears on their brain and get to work considering the levers and pulleys of the filmmaking apparatus. Its opening sequence features a camera and narrated credits, making it clear that the camera, together with the featured players and the product they create, is a subject in itself. Godard, who died in September after a half-century-long career breaking the boundaries of cinema, used Contempt to highlight the industry’s smarmy men, satirize its dependence on money from rich financiers, appropriate contemporary visual aesthetics, and even trouble the so-called male gaze. Recently, Irish artist Jean Curran took Godard’s insistent request as a dare and created Godard/Bardot, a series of 13 handmade dye-transfer photographs printed from the stills of Contempt’s original reel that actively engage with the film’s themes — just in time for the movie’s 60th-anniversary restoration and screening at Cannes.

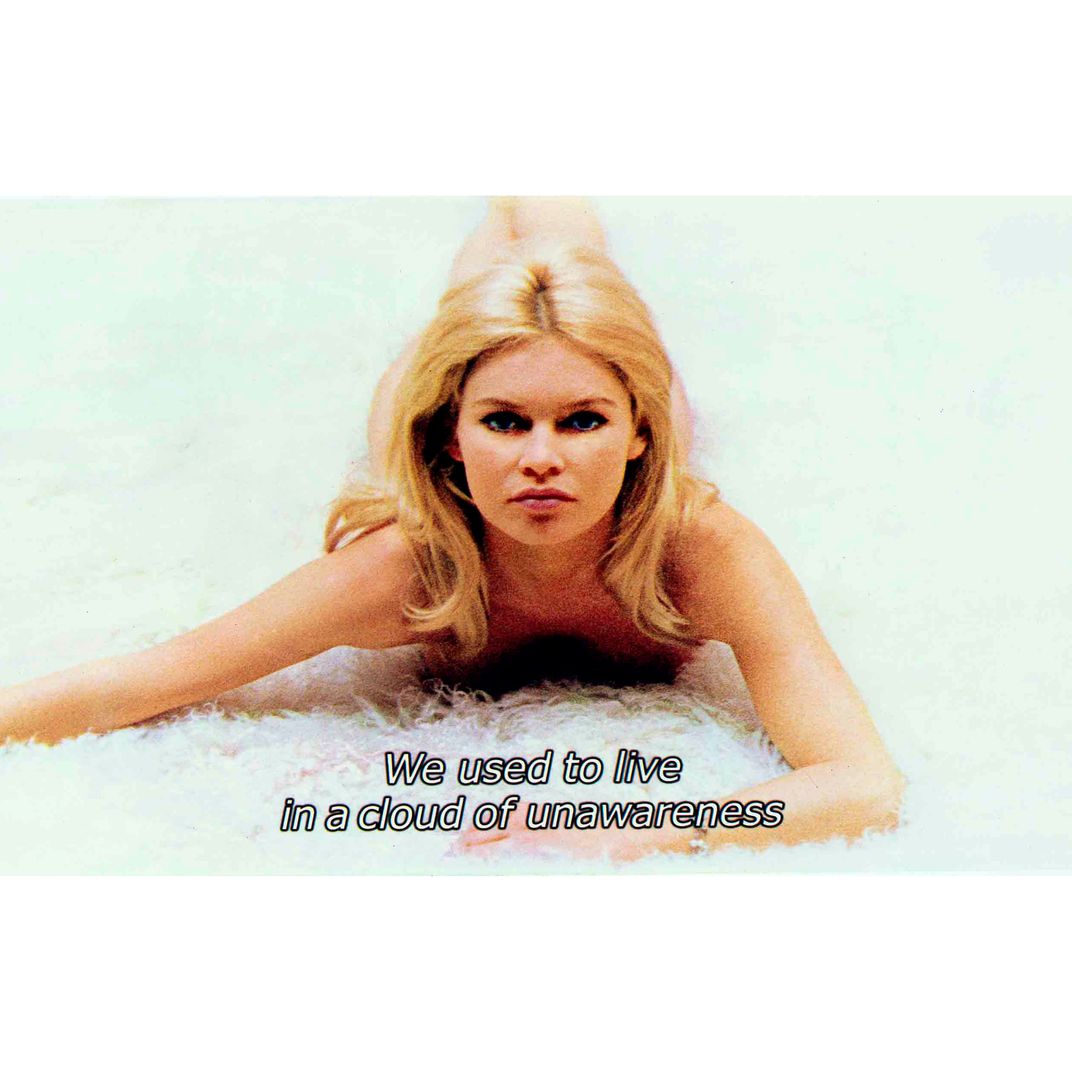

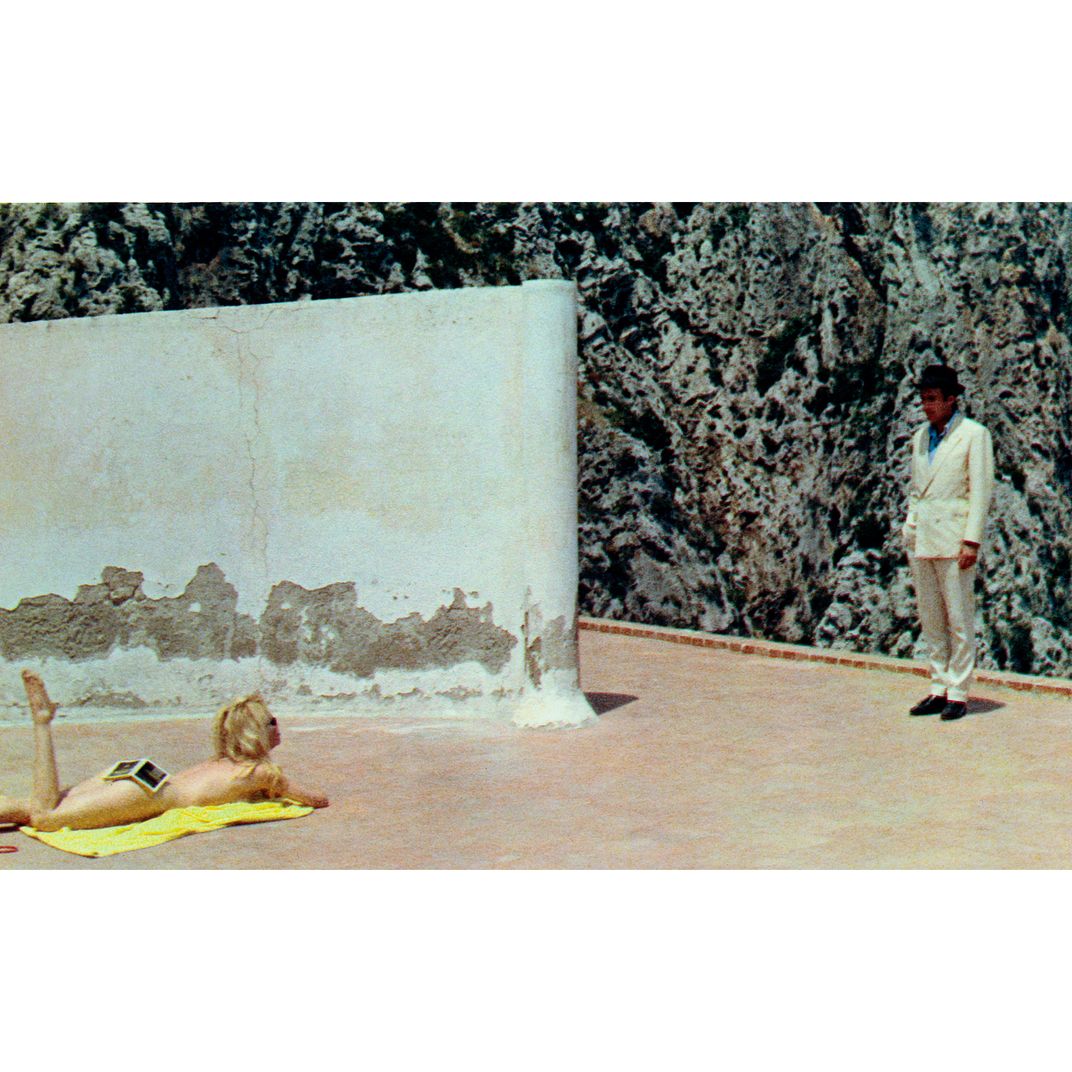

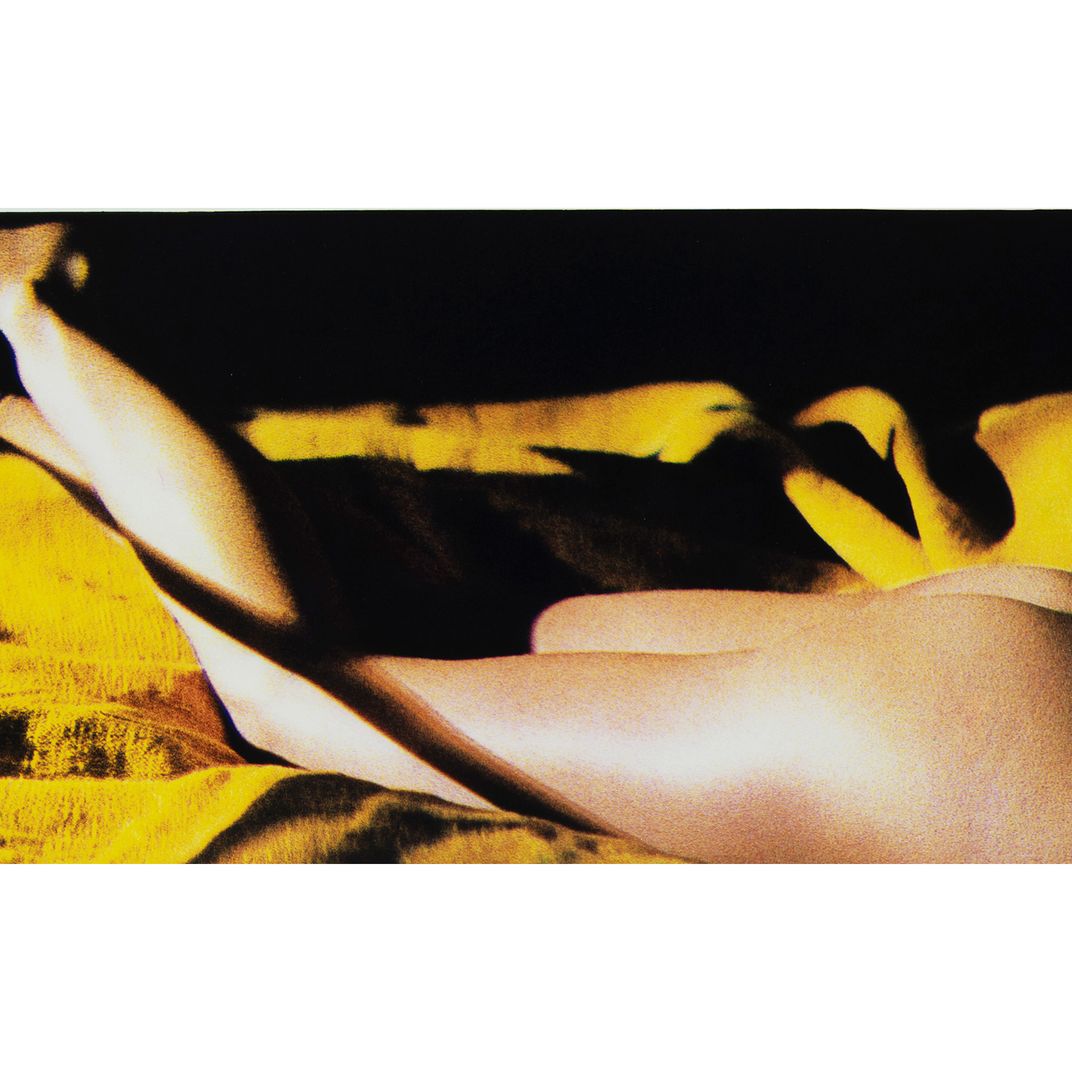

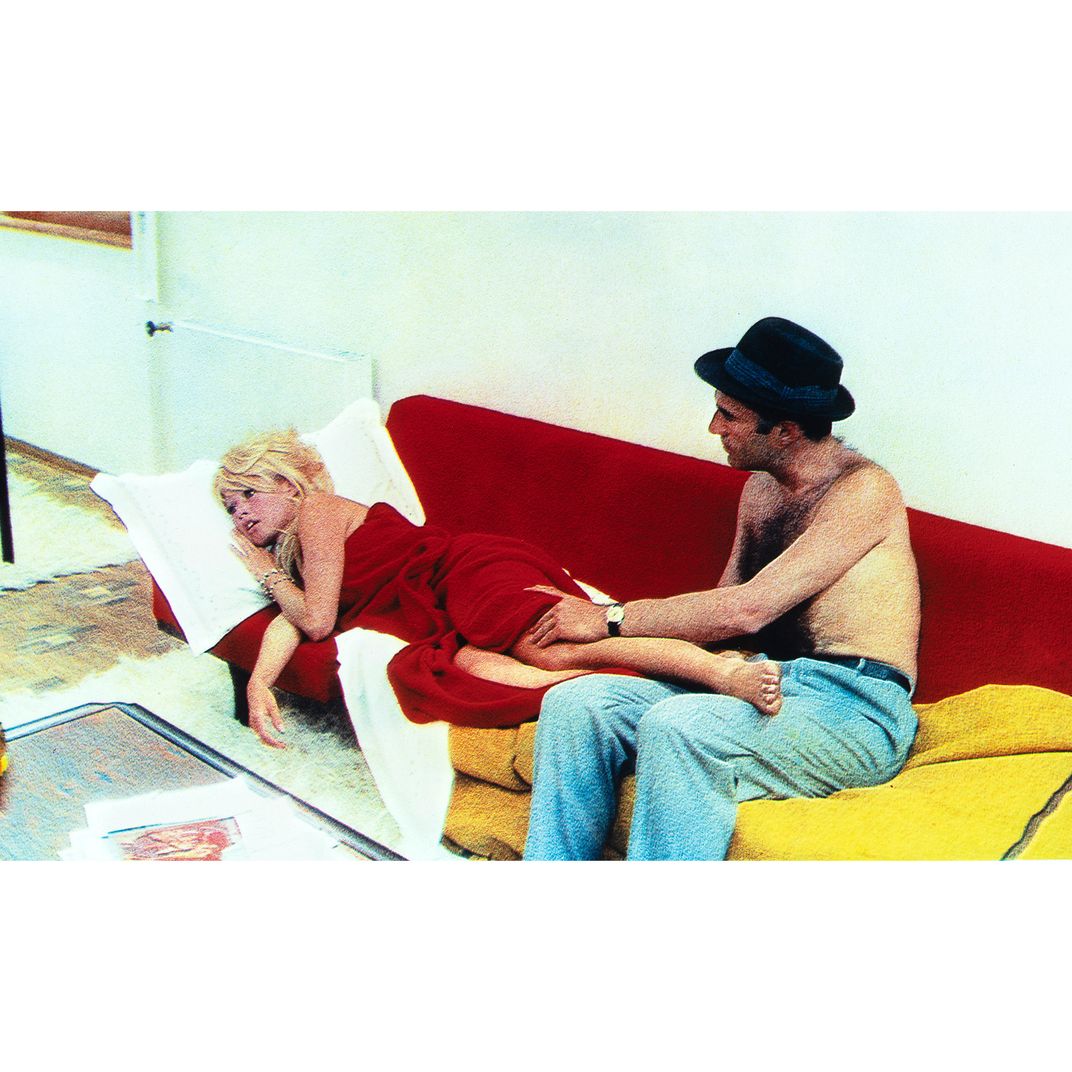

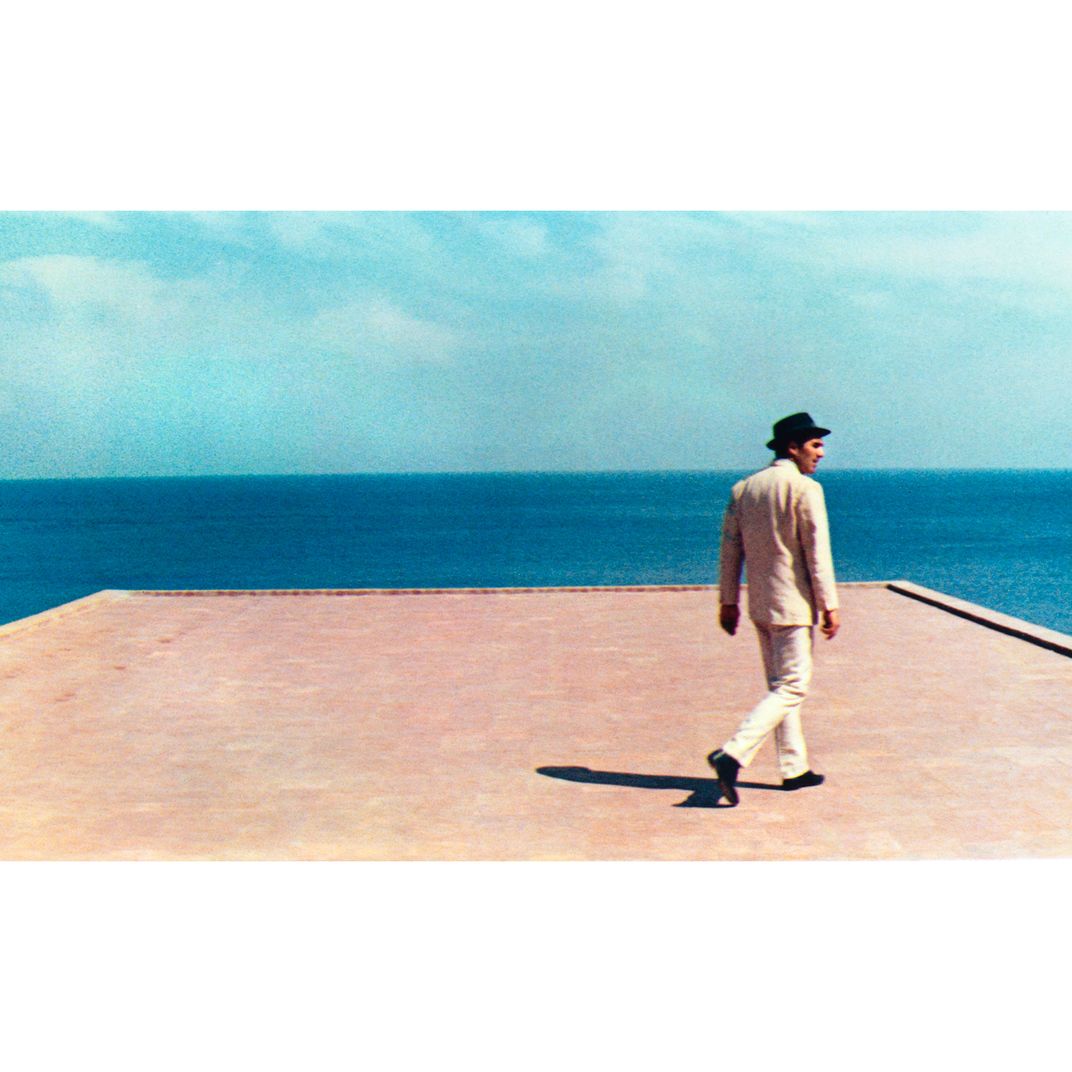

Curran’s latest body of work finds its thesis in Contempt’s depiction of French bombshell Bardot. The actor plays Camille Javal, who grows frustrated with her inept husband, Paul, who has been pawning her off to an American producer who shamelessly flirts with her. Paul wants to secure his paycheck and the opportunity to write his Odyssey adaptation for famed director Fritz Lang, so he lets the man keep hitting on his wife and even says he’s unbothered by the idea of the two spending time alone. Camille is infuriated by her husband’s behavior — hence the title — but she’s not submissive and makes her own decisions about how to deal with her own objectification. “She’s in charge and in control of her sexuality,” Curran says. Many of the images Curran selected for her project depict Bardot as a typical art-historical reclining nude with a twist: her body appears abstracted and from a distance. “It embodies all of these things: questions about sexual liberty, questions about artistic liberty,” she says. This was the first time Bardot’s agent allowed the actor’s nudes to be depicted in such a manner.

Curran’s images, presented by Galerie Miranda in Paris, take the New Wave director’s color film and render it in lush detail in her chosen medium. Curran says that her narrative is partially “about their use of color” and what she sees as a continuation of Piet Mondrian’s investigation into saturated bursts of primary color and Yves Klein’s sumptuous blues. Dye-transfer printing was one of the earliest methods of creating a full-color photograph, using multiple filters to create an image. The process involves separating a film positive into three color channels — red, green, and blue — and making a series of negatives to expose onto sheets of matrix film. Once developed, they are dyed using cyan, magenta, or yellow and transferred onto paper. It takes multiple layers of color to form one photograph, making for rich prints of overwhelming intensity and saturation. The method is similar to how Technicolor films are processed.

“It takes time to get things right, to feel like you honored the intention of Godard and everybody,” Curran says of her project, which she began in 2020 after getting the go-ahead from rights holders StudioCanal, Godard, and Bardot. “It’s very much about having the freedom to be the artist you want to be. He’s referencing so many things and movements within it and was the first person to break filmmaking open and move forward.”

Check out a few images from Godard/Bardot below.