Ten paintings. Each engaging; each mysterious; each stranger than the next. Vivid color, erotic tension, mistrust, and atonement for what society has deemed are perverse games of sexual desecration. The figures in Kyle Dunn’s Night Pictures, now on display at P·P·O·W gallery, exist in suspended states of crisis, in the throes of jealousy and loneliness, withdrawn into shadow — burned out, exhausted, beautiful.

In Paper Angel, a naked male figure is crouching alone in a room, in front of a mirror, looking at a pile of books, food, and other paraphernalia. He personifies procrastination as a creative force. Is he the subject of an invisible painter, the painter himself, or an apparition for a painting? A paper cut-out of an angel adorns the wall, witness to a prayer of desire. The painting is also a superb topological map of open wounds. Here is a world without eros, no “other.” Just wistful longing.

Dunn does the kind of representational painting that places its subject firmly at the center. Unlike, say, Kehinde Wily, whose subjects produce brightly lit stand-offs between the fiercely decorative and the blandly conceptual, lacking drama or even melodrama, Dunn, 33, is more concerned with moments of intense, strange emotion. The results feel new.

The Hunt is an update of Balthus’s “Thérèse Dreaming,” from 1938. In the latter a girl lounges with one foot on the ground, and the other raised on a stool so as to hike her skirt high enough to give a glimpse of her underwear. In Dunn, we get something cooler, if more graphic. A young man poses on top of a dresser. Its drawers are all partly open. He poses as if throwing his leg over a horse. His shaved penis and scrotum are seen, center right, and then again in a smaller mirror. He wears a white go-go boot on one foot, while the other foot is socked and rests atop a pile of books. A print of Brueghel’s “Hunters in the Snow” can be seen propped up against the dresser. All the nascent sexuality and guttural taboo of Balthus is thwarted. Instead, there is a boy looking at himself, or posing as if some young Apollo to be looked at.

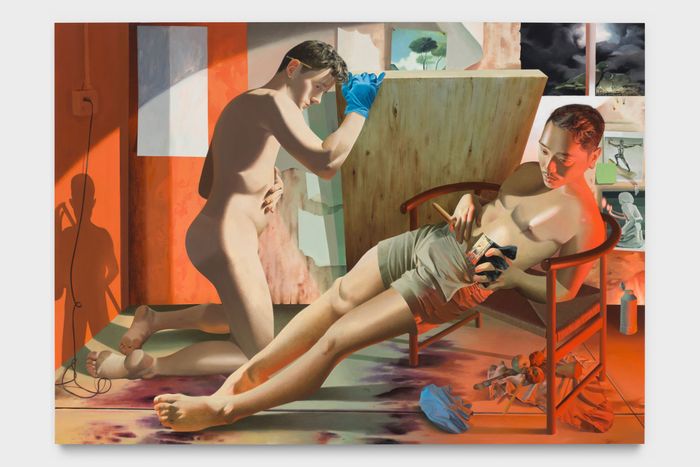

Downward Dog is a play on a yoga pose and a submissive sexual position. A dog, near a figure in the pose, seems to mock the idea. Basement Studio gives us two male figures, one nude, the other in shorts. The former holds his upper abdomen as if he were pregnant. The latter sits on a wide wooden chair, holding a paintbrush as he combs his fingers through it. Pinned to the wall are what look like photographs of old statues — all these realms of artifice, illusion, reality, a world ravished in lunar beauty.

Still Life with Hellebore features a beautiful but toxic flower. Is it something to look at but not touch, or to touch and be poisoned by? Coat is a trompe-l’oeil scene of what looks like a window onto a terrace, with a naked boy outside. It reads like a mirror image of the artist himself. The coat over the mirror turns the figure into a watching adult. This kind of doubleness and weird perspective haunts Dunn’s art.

Finally, in Desktop, we see a character looking down. Or are we looking over his shoulder, spying, participating, preying? The figure crouches before an unfinished painting. Things are unresolved, open; tools, cups, bottles, tape, brushes, and other things are there. We aren’t sure of what we’re looking at because the painting is, on the one hand, serious, composed; on the other, it is playful, mischievous. I see a desperate attempt to create an alternate version of reality, one devoid of plot — a death drive, perhaps. Out of it, something peaceful grows.