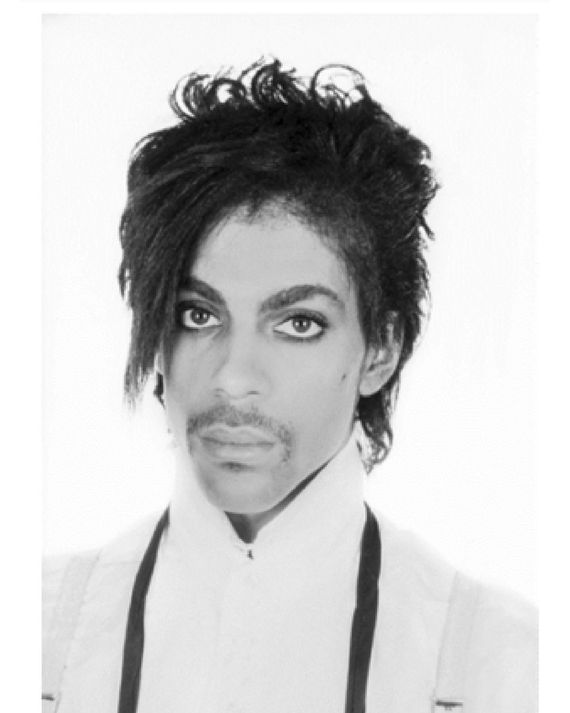

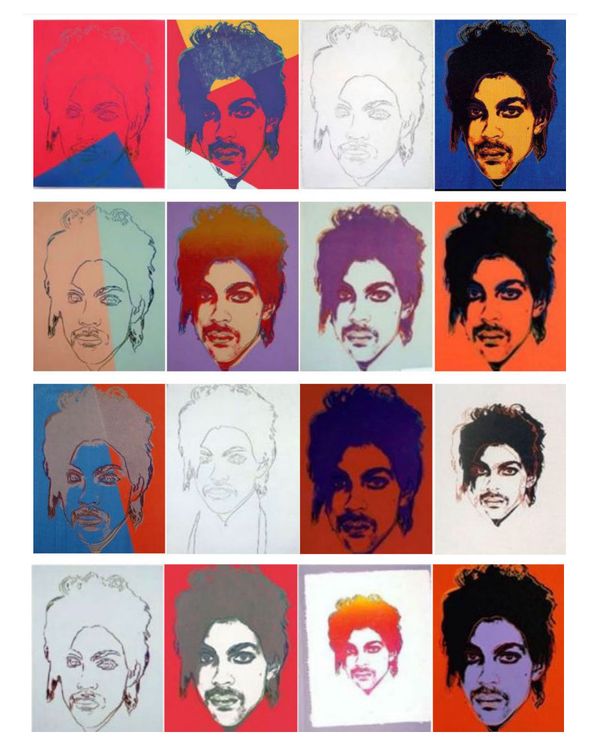

The original photograph of Prince, taken by Lynn Goldsmith in 1981, is a standard magazine-profile shot. In black-and-white, the musician returns the camera’s open gaze. Andy Warhol’s version, made in 1984, is a wholly new and original thing. First, Warhol changed mediums, employing silk screen. Second, he added colors — colors that are singular in art history. He also made several duplications of Goldsmith’s image in what would become known as his “Prince Series.” Each of Warhol’s Princes is quite different from the others, as if a very slow cinematic change were taking place, as well as from the source that inspired them.

The Supreme Court disagrees. In a lopsided 7-2 decision, the Court ruled this week that Warhol’s Prince is not transformative enough to count as “fair use” of Goldsmith’s Prince. The ruling inspired a passionate dissent from Justice Elena Kagan, who warned that the Court’s narrowing of “fair use” laws “will stifle creativity of every sort. It will impede new art and music and literature. It will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It will make our world poorer.” Justice Sonia Sotomayor, writing for the majority, dryly noted that all the Court is asking the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts to do is pay Goldsmith “a fraction” of the proceeds from the licensing of the “Prince Series”; it isn’t banning such appropriations outright. Still, Kagan had a point when she declared, “It is not just that the majority does not realize how much Warhol added; it is that the majority does not care.”

Even a cursory glance at the “Prince Series” is enough to establish that Warhol transformed Goldsmith’s work. Just look at those highly polarized, Day-Glo colors. Before Warhol, no one had thought to combine them this way. Now, these color combinations are in the ads we watch and the designs we purchase. This was a revolutionary formal leap. Even the cropping radically alters the image, with Prince’s disembodied head floating against a bright backdrop as if he were a cutout. The original image exists in a totally different universe, in humdrum reality.

For Warhol, Goldsmith’s photograph was material as malleable as clay, which itself is a comment on the images that form the visual landscape of our lives. Anyone who has taken “Art History 101,” as Kagan notes, knows this. And everyone does it. The Court seems oblivious to one of the great imaginative engines of art of the past 150 years, planting itself, as Kagan writes, “in the ‘I could paint that’ school of art criticism.” Think of Elaine Sturtevant and Robert Rauschenberg. Think of all those artists who use photographs as inspiration or jumping-off points, combining them, drawing or painting on them, sculpting them. Jeff Koons turned a photographic image into a gaudily painted wooden string of puppies.

But he too had to share the profits for using the original found photograph. And here’s the interesting wrinkle about the Court’s decision: The art world may be on its side.

Remember Richard Prince’s series “New Portraits,” created in 2014? Each painting is an inkjet image of someone else’s Instagram page printed on canvases measuring about six feet by four feet. The process involved his adding a comment or two on the page, then taking a screengrab with his iPhone and emailing the file to an assistant. The file was then cropped, printed, and stretched, and presto: It’s art. Richard Prince’s art.

It drove people around the bend with anger. The fact that Prince was an older man using images of younger, often scantily clad women contributed to the outrage. But the group mind came down hard on Prince for appropriating other people’s images without permission. In an Artnet article titled “Richard Prince Sucks,” Paddy Johnson wrote that Prince’s art was “thin offerings for anyone who is in possession of a brain” and that “copy-paste culture is so ubiquitous now that appropriation remains relevant only to those who have piles of money.” My late compadre Peter Schjeldahl wrote that it made him “wish to be dead,” which was “the surest defense against assaults of postmodern attitude.” Anti-appropriation is a common theme these days. Artists, photographers, and influencers are now claiming strident ownership of their images, even when those images are embedded voluntarily into social networks.

The renewed obsession with copyright and proprietary notions about art comes at a time of deep artistic insecurity. Copyright is all but dead in practice, with AI creating images daily based on tens of millions of “remembered” images. The idea of originality is changing, expanding, and there’s no way to put all these genies back into the bottle. In the face of this existential challenge from computers, the creative industries could allow human interpretation and adaptation to flourish instead of fearfully putting rings around what they’ve already made. Goldsmith told Hyperallergic, “This is a great day for photographers and others who make their living from licensing their art.” She added, “I hope this SCOTUS ruling is a lesson.” I’m afraid it is, just not the one Goldsmith thinks.