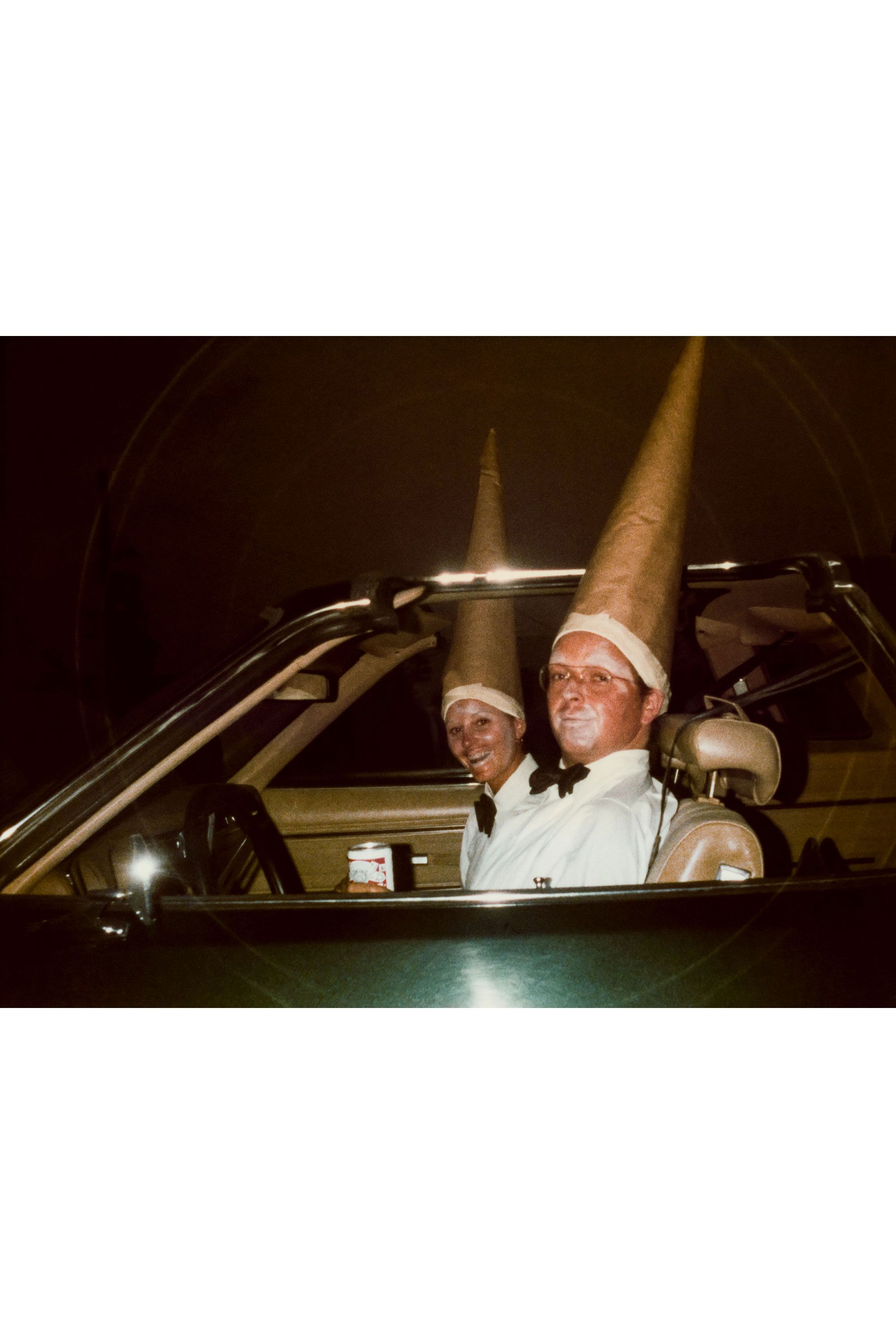

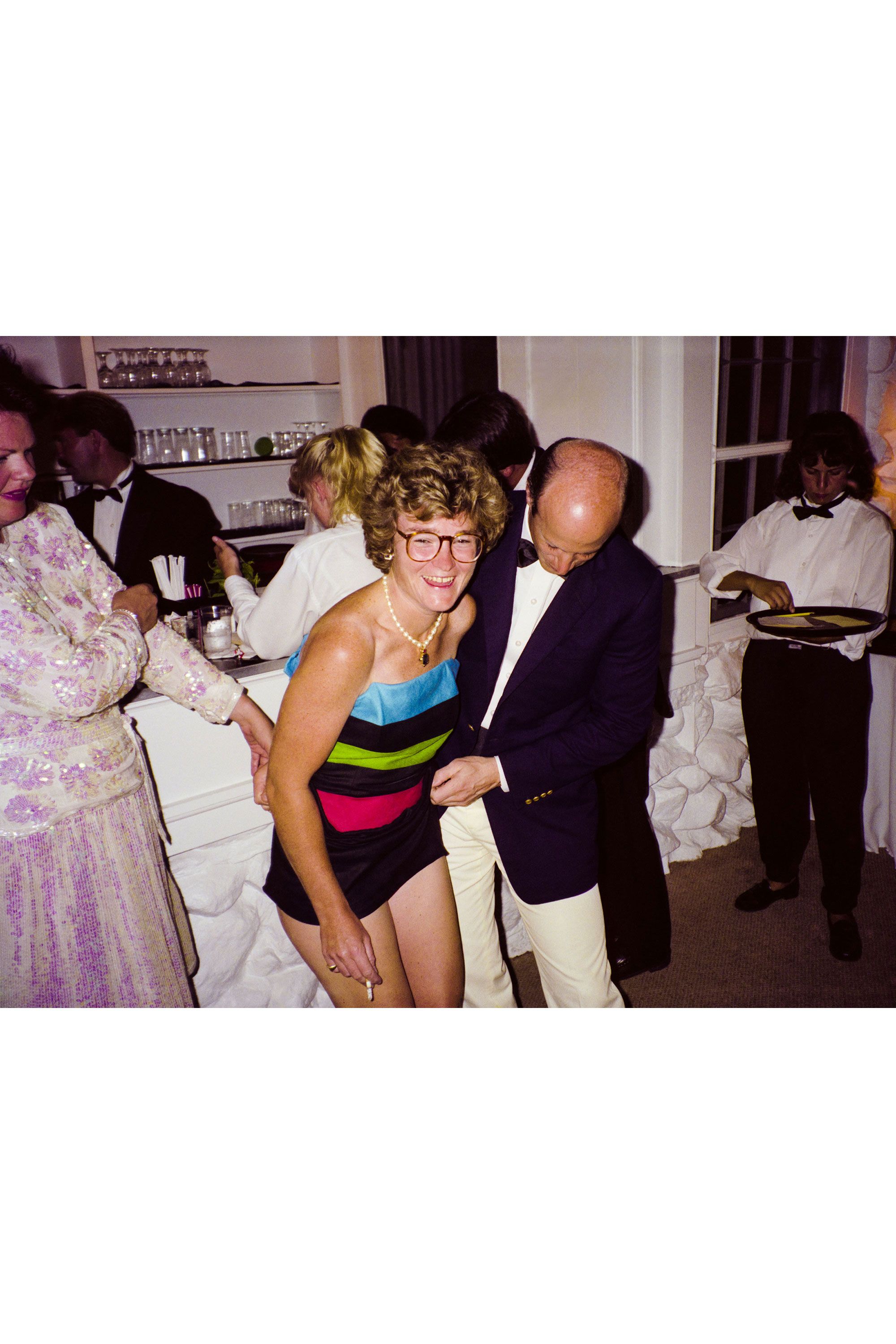

The people we see in Will Vogt’s These Americans are more than affluent. They are the old Eastern aristocracy, of F.R. Tripler & Co. blazers and big unruly dogs named for alcoholic spirits (Brandy, Whiskey) and summers in Newport. Vogt grew up in this world, on the Philadelphia Main Line, and starting in 1969, when he was 17, he took a seemingly endless number of pictures among his friends, associates, and neighbors. (He later moved to Texas, and many of the pictures in These Americans were made there.) Perhaps because he was of the same class as they, his subjects betray no sense that he was more than a snapshot photographer; there was zero fear of public exposure. “People wanted to be photographed,” Vogt says today, “’cause they weren’t afraid where it was going to go. There was no instant dump onto your social media and Oh, well I don’t think I want that.” The best of the pictures went into albums that Vogt kept at home, and they weren’t any kind of a secret. “My biggest complaint was people would say, ‘Goddamn, you take all these pictures. Where are they? When do I get to see ’em?’ And I would say, ‘You come over to my house and flip through these albums, and you can look at ’em to your heart’s content.’”

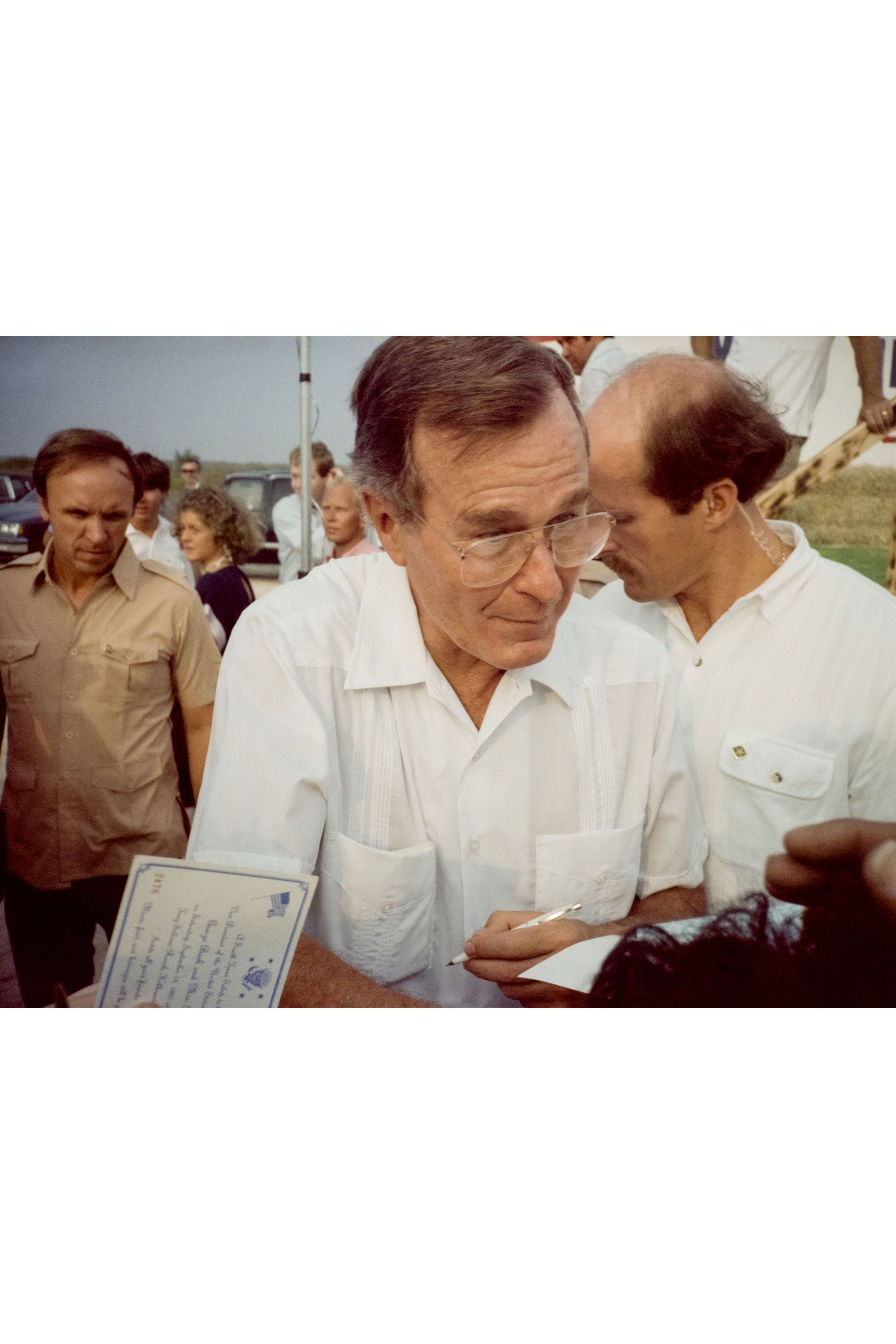

These Americans, just out from Schilt Publishing with an introduction by Jay McInerney, draws from that 70,000-frame body of work. The selection runs through 1996, falling heavily on the 1980s, and the unself-consciousness on view is astounding. Everyone is at ease in this milieu, whether backstage at a wedding or gathered around the bar or the pool. Especially in the earlier photos, the old preppies are always smoking, of course. There are no famous faces on view save one — George H.W. Bush, who pops up briefly in a sport shirt. (A few frames, though not many, are outré: some coke, a couple of streakers.) It’s implied that most of these subjects regarded Vogt as just a friend with a hobby, on the fringes at family-and-friends gatherings. It didn’t hurt that he usually worked with nothing more than a modest point-and-shoot camera.

These days, the world of dynastic wealth — while still extant — is both diminished and changed. Distinctive clothes and habits that once seemed like Just the Way We Live are now codified as “American preppy style,” and outsiders peer into the clubhouse as they once could not. (Not to mention that the old attitude of “your name should appear in print only at birth, marriage, and death” seems quaint in the age of the influencer.) Was Vogt consciously looking to document that world before it slipped away, or was he just having fun taking pictures of his own crowd? “Well, I think a little bit of both,” he says. But the more he talks about his intent, it seems to have been less toward the historical record and more toward simple, personal aide-memoire. “I was influenced by my mother, and she took pictures in the ’50s and ’60s. I mean, she wasn’t a photographer — she was, you know, a housewife that took pictures. That’s what people did. And more importantly, she put ’em in albums. So many people take all these pictures and they’re in desk drawers, or under the bed or in the closet.”

The title — as well as the book’s horizontal format and cover typography — makes obvious reference to Robert Frank’s The Americans, the landmark 1959 collection that busted open so many photographic conventions. (Vogt says that he greatly admires Frank’s work, and also adds, ruefully, that he should have collected it back when it was a lot cheaper.) Although the visual milieu here is different, Vogt, like his predecessor, declines to identify who everyone is. “We thought about it, and we really want the pictures to speak for themselves,” Vogt says. “We kind of like the mystery.” There are no captions at all in Vogt’s book, although he says that a future exhibition might include some very minimal ones.

That said, he was a little more forthcoming when I asked him about one guy who appears more than once in the book. “He was a very interesting family friend who was very wayward, a professional inheritor who wasn’t any good at it. Married a couple of times, but had no children. And he died way too young, because he didn’t take care of himself.” He was, Vogt suggests, that person who just always turned up, and you yourself may have dozens of photographs of someone a little like him on your phone or in your drawers and albums; I certainly do. “He was, you know, kind of our class clown, on the tip of everybody’s tongue. People loved him. So this book is somewhat dedicated to him, kind of.”

These Americans No. 111.

These Americans No. 91.

These Americans No. 22.

These Americans No. 18.

These Americans No. 124.

These Americans No. 60.

These Americans No. 33.

These Americans No. 105.

These Americans No. 6.

These Americans No. 55.

These Americans No. 11.

These Americans No. 51.

These Americans No. 82.

These Americans No. 111.

These Americans No. 91.

These Americans No. 22.

These Americans No. 18.

These Americans No. 124.

These Americans No. 60.

These Americans No. 33.

These Americans No. 105.

These Americans No. 6.

These Americans No. 55.

These Americans No. 11.

These Americans No. 51.

These Americans No. 82.