Reza Shafahi is 83 years old. He grew up wealthy in Iran and was a famous wrestler. Then, Shafahi says, his “troubles began.”

“I discovered playing cards,” he writes in the catalogue of his new show, Diary of a Gambler, at Club Rhubarb (one of a handful of superb new galleries on the Lower East Side). His pastime became an addiction that “slowly took over my life until I was left with only one option: I needed to win big to pay off my gambling debts. But I lost, hands down.” He had to leave home. “I remained absent as a father for many years,” he says. His wife, Tahereh, got a job as a teacher and began working all day, every day, until finally she paid off his debts. “I could come out of hiding,” he says.

Ten years ago, his son, Mamali, who is gay — an enormous danger in Iran (he now lives in Paris and makes wildly interesting monochromatic flocked sculptures) — asked him to make a drawing. And to give him a few drops of his sperm. (The sperm was later exhibited by Mamali.) Reza says, “I gave my sperm, and my son Mamali was created. Then my son gave birth to me as an artist.” He now draws every day.

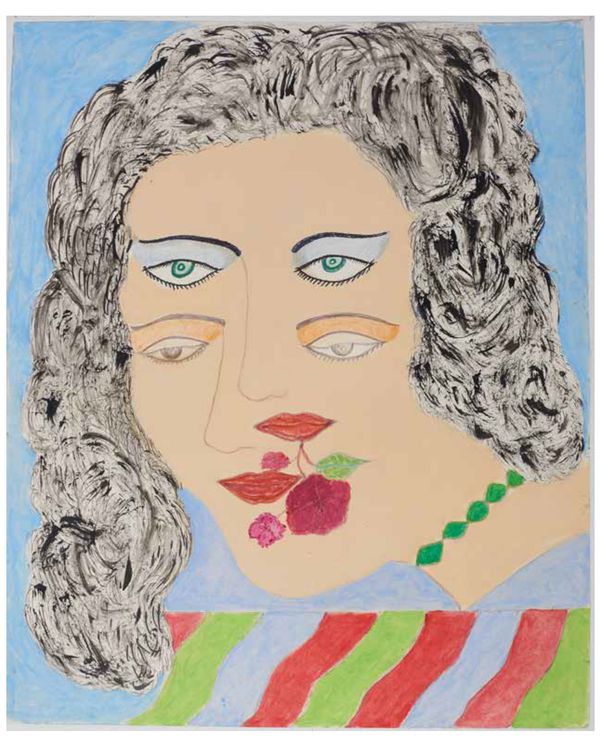

His show features a drawing of a girl with four eyes, two noses, and two sets of lips, each with a flower coming out. Her head floats in profile on a blue background. Her upper set of eyes look up; the lower set looks down. Part Egyptian, part Greek, part opium fantasy, she is a spirit of doubleness.

Shafahi says his work is an homage to ancient Persian culture. “Persian culture is sexual and gluttonous,” he says. “All texts are about desire.” He notes, “My work in four words: Sexual, organic, opulent, vivid.” But the inspiration for many of his works comes from the poetry of Omar Khayyam, Hafez, and Forough Farrokhzad. This is a Persia of the mind as well as the loins.

Made with colored pencils and acrylic paint, his drawings are flamboyant, flowery, ornamental. His touch is easy, magical, spontaneous. “Now my game is built on joy,” he says. “If I had not picked up painting, I’m not sure I could stand myself.” There is a wonderful materiality to the color as well as an immensity to the overall vision.

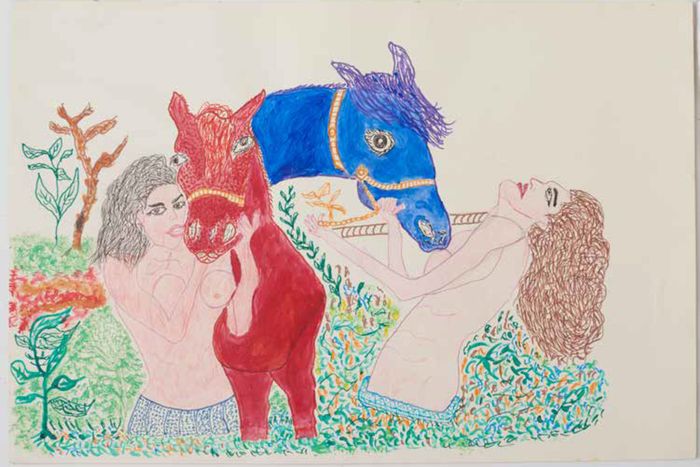

Another drawing gives us another doubling. Two horses — one brown, one blue. Each is held, adored, by a topless woman. Here is paradise, here is freedom, here are things of obscure origin.

Over and over, we see this orgiastic flow of bodies and faces. There are plumed mythical creatures with wings, pleasure palaces, free-floating eyes. There are tattooed females deities holding severed male heads. There’s a tree that seems to sprout three heads. Each face is flat, facing us, a god of nature.

Social content also creeps in. One drawing has a nude female figure, seen from behind. Her arms and legs are chained. Nearby two other naked figures cower or bow. A disembodied hand holds a rifle as an evil face — scrotal, ugly, threatening — hovers. Another drawing depicts a woman wearing a bikini with the top pulled down. She holds a club over a man in the grass. There is blood everywhere. She is beating him to death.

For someone from Iran, this is risky stuff. But Shafahi is used to taking risks. “Drawing is a gamble,” he says. “Art is a gamble.”