Barkley L. Hendricks, who died in 2017 at the age of 71, was best known as a portraitist. His subjects stand in monochrome fields, often looking right at us as if aware that they are being seen. The backgrounds are painted in oil, the figures in acrylic. Rich and nuanced, oil takes a long time to dry and sets up differently than acrylic, which is fast, more plastic, flatter. Hendricks gets them to flow together into a single, transfiguring lake. The figures, at their ease, are filled with aristocratic charisma and poise — what we used to call “cool” before the word lost its meaning. Fourteen of these portraits are now on display at the Frick, where they also make a statement, standing tall next to the Whistlers and Rembrandts.

Hendricks’s earliest work here, from 1969, is owned by the Studio Museum in Harlem. Lawdy Mama pictures the artist’s cousin with a large Afro. She stands like a Byzantine icon, surrounded in gold; the top of the painting is curved, connecting the work to the Renaissance altarpieces Hendricks admired. She is a soft-edged being, as real as she is ideal, mortal and immortal.

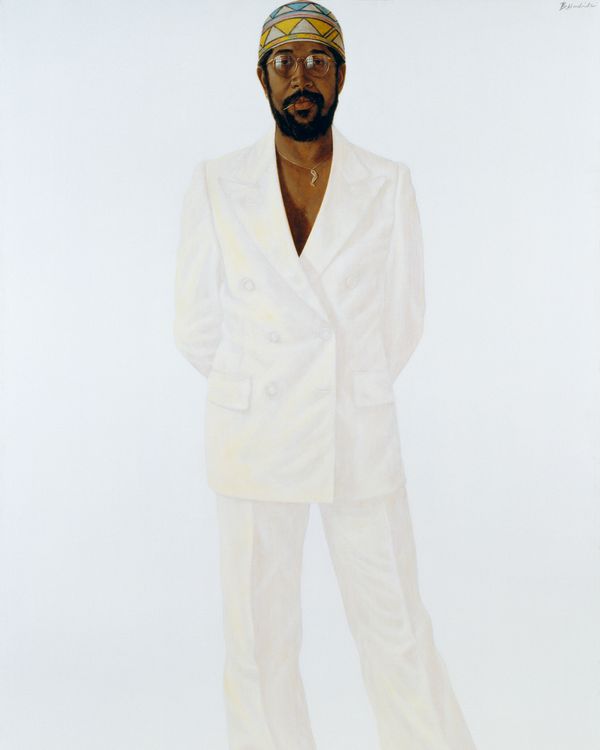

Hendricks had a real feel for body language. And for fashion. His figures are dressed to the nines, their outfits on proud display. Steve wears shades, black shoes, and a glorious white-on-white ensemble — drapey pants, shirt, trench coat — against a white background. Blood (Donald Formey) depicts a man in an incredible plaid jumpsuit with a dapper cap and a tambourine.

The painter was sensitive to how these cocksure representations were received. After his art was deemed “slick” by the conservative critic Hilton Kramer, Hendricks made Slick, a gorgeous picture of a shirtless man in a double-breasted white jacket and flared white pants. He wears a kufi cap and looks at you with seething eyes. When Kramer referred to Hendricks as “brilliantly endowed,” he responded with a brilliant work titled Brilliantly Endowed. That painting isn’t here (c’mon, Frick!), but it features the artist in a full-frontal nude pose wearing socks and glasses.

Hendricks was born in Philadelphia and went to Yale, he said, “to keep my ass from going to Vietnam.” He spent most of his time there “in the basement” with the photographers, as the painters were busy with conceptualism and hard-core abstraction. (One of his teachers was Walker Evans.) He referred to his degree as his “union card” to teach, which he did for decades at Connecticut College in New London, where he raised his family.

He also honed his skills at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Portraiture is a formal problem with extremely limited subject matter — usually a figure seen from one angle, in a room or outdoors, against some ground. Within these narrow confines, painting with delicate precision, Hendricks rendered a beautiful group of impeccable peacocks. The way they are different, as becomes obvious when you are at the Frick, is their race.

The subject of race was a source of anger and irritation for Hendricks. In an interview with the New York Times, he said he was tired of being described as a “political” artist. “Anything a Black person does,” he said, “is put into a ‘political’ category.” He called such designations a “white myopic approach to what I do.” Of his white critics, he said, “It was political in their minds. My paintings were about people that were part of my life.” He added, “How many white artists get asked about how their whiteness plays a part in their work?”

Hendricks demanded to be considered as “a whole artist.” And, of course, race was a central part of his work, as it inevitably must be for someone who was not only Black but whose whole career was conducted in the shadow of an art world that did not show a lot of Black people. His 1978 group portrait Lagos Ladies (Gbemi, Bisi, Niki, Christy) makes a point about how race produces a divided self. It features four women in white just hanging out, regular people who might merely have been part of Hendricks’s life. If this were shown in Lagos, it might not mean much at all. But here, it does. Here, it means a lot.