In the early 2000s, when big-budget, high-profile, blockbuster comedy movies were still a thing, Will Ferrell, Ben Stiller, Vince Vaughn, and at least one Wilson brother popped up in each other’s movies, almost always produced by Judd Apatow. They all factor prominently in Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy, the peak of this so-called “Frat Pack” era. It hit theaters in the summer of 2004 on the heels of other hits like Old School and Dodgeball.

Like other Frat Pack entries, Anchorman concerned a hilariously immature man-child reluctantly growing up by the force of a situation. But Anchorman was also something different and bigger than its predecessors. Set in San Diego (which means “a whale’s vagina” in German, per Ferrell’s title character) in the 1970s, it’s a period piece about the Channel 4 news team, a crew of unrepentant misogynists whose world is rocked with the arrival of the ambitious and skilled “anchor lady” Veronica Corningstone (Christina Applegate), who refuses to take their shit and isn’t afraid to throw a typewriter or sabotage a teleprompter (if she has to).

Anchorman reckoned with America’s ugly sexist history and had a lot to say about toxic patriarchy and workplace politics, but it was also just absolutely packed with jokes and memorable lines, of which approximately 98 percent have been repeated by the initial target audience of dude-bros more than a billion times each. (Hey. It’s science.) Devised, written, and executed by former Saturday Night Live partners Ferrell and Adam McKay (who also directed), Anchorman was a turning point for both creatives, allowing the former to go as big and broad as he’d clearly ached to go and McKay to inject seething, satirical rage into his work, a style he’d explore fully in The Big Short, Vice, and Don’t Look Up.

It’s been nearly 20 years since Anchorman joined the canon of American comedy classics, so it’s high time for a leatherbound-book-length critical assessment and thorough telling of how it all happened. Saul Austerlitz, a comedy history professor and author of the definitive pop-academic book about the sitcom Friends, did the research, interviews, and investigative reporting to make Kind of a Big Deal: How Anchorman Stayed Classy and Became the Most Iconic Comedy of the Twenty-First Century. It’s apparent that Anchorman was both a hard and easy film to make, with studio interference often looming over a laid-back set where improv and cast bonding weren’t just encouraged but required. Some of the best parts of Anchorman emerged from this comedy-lab approach, which meshed well with the crew’s exhaustive attention to detail. Here’s an excerpt from Kind of a Big Deal, “Letting the Squirrel Out of the Bag.”

An Excerpt From 'Kind of a Big Deal: How Anchorman Stayed Classy and Became the Most Iconic Comedy of the Twenty-First Century'

It was an unspoken custom on most film sets to never offer an opinion on another actor’s performance. The actor’s work was fiendishly difficult, requiring them to expose themselves in a fashion that nonperformers could only relate to from their sweat‐soaked nightmares, and the effort that went into even the most mediocre performance had to be respected by their fellow practitioners. But the actors on Anchorman had mostly been forged in the white heat of sketch and improv, where performers regularly topped, completed, or added to the work of others, and that spirit carried over to the set of this feature film.

This began in McKay’s relationship to the performers. He was present not solely to oversee or to hector but to lead a graduate seminar in the creation of comedy. Every line could be improved or rendered funnier or stranger, and everyone was encouraged to contribute. This spirit of creative generosity came to include all the performers, who embraced the freedom to reimagine the film one line at a time. By the start of the shoot, the script had been through table reads, rewrites, and punch‐ups, and McKay and Ferrell were confident that the jokes were solid. Even if all they accomplished was filming the script exactly as written, they would be in good shape. But they were hoping for more.

McKay rapidly established a routine on the set. The actors would film two or three takes of a given scene, following the script to the letter. Once McKay felt confident that they had captured the essence of a scene as scripted, he would raise his voice and call out to the cast and crew: “Let’s let the squirrel out of the bag.” Koechner understood McKay to be declaring, “Say anything you want, and see if it sticks.” McKay was opening the floor to input from himself, Ferrell, Apatow, the actors, or anyone else with a kernel of an idea for how to improve, twist, adjust, or reorient a sequence. They called these takes “alts.” McKay, possessed of a naturally loud voice, did not need a megaphone or a “voice of God” microphone connected to speakers around the set. He could simply shout and make himself heard while standing behind the camera or sitting next to a monitor inside the video‐village tent, which perhaps added to the informal, try‐anything mood. Ferrell had already done his homework the night before shooting a scene, reading once more through the script in order to jog his memory about additional lines he might try out the next day. And the script supervisor’s notes would also allow him to have a reference nearby, reminding him of what he and the cast had previously attempted during rehearsals.

Alts were a game, and performers who had been trained in improv comedy, and knew how to read a scene and grapple with its potential, were at a distinct advantage. The first few takes had been to serve the script, and even this open‐mic style had to preserve the outline of the story. A line could be hilarious, but if it contradicted the remainder of the text, it would be unusable. You had to be able to read the mood of a line and substitute another idea that extended or amplified or twisted the joke. Some performers, like Fred Willard, who had worked extensively with Christopher Guest on films like Waiting for Guffman, were used to being handed little more than an outline and a précis of the information contained in a scene. Others, like Applegate, were more familiar with comedy that was entirely scripted. McKay’s style combined scripted and unscripted approaches, demanding a confluence of skills from his performers.

The origins of the phrase “letting the squirrel out of the bag” are lost but might have something to do with a sequence early in the film. The news team gathers in the conference room the morning after an epic bender. Champ, his tie undone, his hat pushed back on his head, a square of bloody toilet paper stuck to his face, says, “I woke up this morning in some Japanese family’s rec room and they would not stop screaming.” That got a positive response, but then Koechner came up with an entirely different run (which would be used for the unrated DVD cut of the film): “I woke up this morning and I shit a squirrel. I mean it. Literally. Hell of it is, damn thing’s still alive. So I got this shit‐covered squirrel down there in the office. Don’t know what to name it.” (In another take, Champ said his night had consisted of six bottles of white wine, pissing his pants, and shooting stray dogs in Mexico.) Koechner had planned to go on with his run, talking about how he was not sure if the squirrel had shit on it or not, but was interrupted by the pleasant sound of his castmates’ bursting into laughter and ruining the take.

To be truly brilliant at letting the squirrel out of the bag, it was helpful to listen attentively to others’ work. Alts demanded heroic reserves of improvisatory creativity, which could easily inspire a narcissistic attention to your lines and no one else’s, but the game worked best when actors bounced off each other’s runs. After Koechner described shitting a squirrel, Steve Carell stepped forward and demonstrated how carefully he had paid attention to Champ’s morning‐after, bent through the broken aperture of Brick Tamland: “I’m sorry, Champ. I think I ate your chocolate squirrel.” Koechner was deeply impressed that Carell had listened so closely and was able to craft his own alt to the alt. An entire night was devoted to Carell’s infinite variations on this morning‐after sequence, including one alt that would make the film’s outtakes: “I ate a whole bunch of fiberglass insulation. It wasn’t cotton candy like that guy said. My stomach’s itchy.”

It might have been possible for McKay and Ferrell to write the squirrel joke, given enough hours, enough caffeine, and enough bursts of inspiration. But sometimes the best material came from turning over your highly polished script to others. McKay would tell actors that nothing could ever compare to the feeling of showing up on the day you were to film a scene, surrounded by the sets and the costumes, and letting your mind wander. The film would ultimately begin with a sequence knitted out of alts, with Ron warming up before a broadcast with a series of ludicrous vocal exercises, including “The arsonist had oddly shaped feet” and “The Human Torch was denied a bank loan” (which received the biggest laugh on the set). Ron also banters with offscreen figures, attempting to puzzle out one’s name (is it Lanolin?) and picking at his teeth as he informs the no‐doubt‐fascinated crew that he ate ribs for lunch that day.

The opening, too, would emphasize the boozy, degraded vibe of News Channel 4, with Ron preparing for the night’s broadcast by stretching to drain a glass of scotch and then sharing his enthusiasm with others: “I love scotch. I love scotch. Scotchy‐scotch‐scotch. Here it goes down. Down into my belly.” Ron’s voice takes on a singsongy quality, as if this were the theme song to his existence or the fuel that powers him through each night’s news.

McKay was creating an atmosphere that went against so much of the conventional wisdom of the film set. Letting actors play around as the cameras rolled was, generally, seen as the literal embodiment of setting cash on fire. Every foot of film, every minute of crew members’ time, costs money, and opening the floor to let others play around on a film set was a recipe for utter chaos.

Some scenes had a hyperabundance of possible lines from which to select, while others did not have quite enough on the page to come to life. While shooting the “Afternoon Delight” sequence, in which Ron fills in his colleagues on the meaning of love by leading a barbershop quartet version of the Starland Vocal Band hit, McKay approached Carell and told him, “We should have more lines for you, but we don’t have any on the page.” McKay asked him to jump in anyway: “Just say something.”

McKay understood Brick as the Harpo Marx of this ensemble. Brick was less subject to the laws of physics, or the requirements of realism, than his fellow characters. He could comment on scenes or break the fourth wall without warning. McKay saw it as a magical power that was granted to Carell, but one that had to be used sparingly, for fear of spoiling the effect. After Ron waxes poetic about Veronica, Champ haltingly asks: “What’s it like, Ron?” Ron takes his question to be about sex at first: “The intimate times? Outta sight, my man!” But Brian has a knottier and more shameful query in mind: “No. The other thing. Love.” Love comes out as barely a whisper, with Brian closing the door before even saying the word.

After Brian’s brief tribute to the Brazilian — or Chinese? — woman he made out with in a Kmart, Brick leaps in with his own interpretation of love as his eyes scan the room: “I love carpet.” Ron nods encouragingly, and Brick continues: “I love desk.” Ron — and Ferrell — catches on to what Brick is doing here and gently calls him out: “Brick, are you just looking at things in the office and saying that you love them?” Carell’s delivery here is a master class in intonation and rhythm. He stands ramrod straight in his three‐piece brown suit, his eyes skittering to the side before facing forward, his voice lowering to a husky whisper: “I love lamp.” When Ron asks again whether he really loves the lamp, Brick repeats his line, but this time with a tinge of sadness, as if lamp were the one who got away. It was pure brilliance, and only the improv process could have created the moment.

The key traits needed in order to capture improvisational lightning in a bottle were patience and an ability to mentally reset. For the sequence in which Ron and Veronica sit in a car looking out at the lights of the city (shot on an overlook point near downtown San Pedro), Ferrell tried out an astounding variety of differing lines to describe San Diego. The crew kept shooting, going through four or five magazines of film as he trotted out alts — almost an hour of hectic improvisation along the lines of “San Diego, which of course in German means ‘golden pancakes.’” The camera crew was getting colder and colder in the brisk evening air as the shoot went on and on. With each variation, Applegate would have to respond as if for the first time, squinting her eyes or pursing her lips and registering her uncertainty at Ron’s urban knowledge.

McKay would occasionally chime in with suggestions but mostly let Ferrell operate under his own guidance, testing out different approaches to the moment before settling on the version that had appeared in the script: “I love this city. It’s a fact. It’s the greatest city in the history of mankind. Discovered by the Germans in 1904. They named it San Diaago, which of course in German means ‘a whale’s vagina.’”

McKay and Ferrell also tried out a series of options for the line Ron would deliver on camera that would drive away his loyal fans in a later scene. The final film kept it simple, with the teleprompter‐dependent Ron accidentally telling his audience, “Go fuck yourself, San Diego,” at the end of a broadcast. Veronica sits next to Ron, frozen in shock that her ploy to fix the teleprompter has actually worked. “Ron, I’ve got to fire you,” an ashen Ed tells him, and Ron playfully responds, “Well, I’ve got to fire you. Bing‐bom‐bom.” Ron points finger guns at his boss and walks away chuckling at Ed’s joke. It is not until Ron is shown a video playback of the broadcast that he blanches, his eyes bulging in shock: “Great Odin’s raven!” Numerous alts were trotted out for this moment, with McKay especially partial to a filthier version: “Go put a huge, purplish, veiny cock up your ass, San Diego.”

The alt style was a particular challenge for the camera crew, who had to find a way to keep the camera following along with performers without knowing precisely what they might do in any given sequence. Normally, a scene might last forty‐five seconds at maximum, giving crew members an opportunity to adjust, but the camera could be rolling here for minutes at a time. Camera operator Harry Garvin had pored over the script but would find himself adrift after the first few takes. Garvin began to study each performer’s tics to grasp what they might be doing. He noticed that Ferrell would punctuate many scenes with the glass of scotch that was often in his hand. He might bring it up to his lips, say his line, and then drink it, or merely bring it close to his mouth. Applegate would tilt or twist her head in a certain way each time she was listening to one of Ron’s monologues.

One Friday afternoon, Ferrell, Koechner, Rudd, and Carell were shooting a scene in the news station’s cafeteria (the same scene Carell had auditioned with), planning their latest assault on Veronica, which Champ cruelly compared to their earlier campaign against “that limp‐wristed fairy that was supposed to do the financial reports.” Ron agrees that they’ll “declare war on Corningstone” but is distracted by Brick’s falafel–hot dog–cinnamon lunch. The news team bursts into over‐the‐top laughter at Brick’s appalling meal, while Carell enthusiastically eats, his teeth dusted with a thick sprinkling of coffee grounds. The other actors struggled to hold it together as Brick obliviously munched.

Without explicitly announcing any competition, Anchorman’s performers were looking to amuse each other, and Carell was preternaturally gifted at setting off helpless laughter in his costars and in the crew. Carell thought of himself as a spectator on Anchorman, which he saw as aligning with his role. Brick was mostly in the background, with fewer lines than his compatriots, and yet what Carell most wanted to get across was Brick’s desire to be part of this dysfunctional but loving team.

David Koechner had been given a beige cowboy hat with a tilted brim and flared sides as an all‐purpose accessory. Costume designer Debra McGuire saw Champ as the cowboy of the story — crude, boisterous, and powerful — and wanted to assign him headgear that fit the character. The thing about the hat was that it was ever‐so‐slightly too large. This was a flaw and also a jury‐rigged solution to the problem of Steve Carell, allowing Koechner to dip his head and partially cover his face when Carell made him laugh. (It was so hard not to laugh in the presence of these performers that Koechner was sometimes reduced to thinking of difficulties his children had endured in order to avoid breaking.)

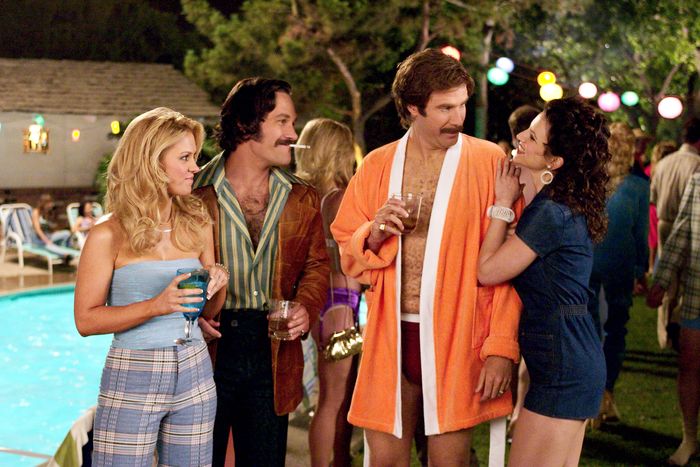

One of the earliest sequences committed to film, the party sequence at which Ron first spots Veronica, was a night shoot on location in the neighborhood of View Park, and a chance to set the tone for the team — and the whole film. The location was a house that was a true 1970s holdover, complete with shag carpeting and globe lights lining the street. (Another house scouted by location manager Jeremy Alter belonged to Ray Charles and featured a piano‐shaped pool.) “Are we in a time warp or something?” camera operator Linda Gacsko wondered when she caught her first glimpse of the location.

The house party serves as the Channel 4 news team’s first opportunity to introduce themselves. Brian, in a creased tan leather jacket, flashes a gun and smokes a cigarette, his arm around a sultry blonde (Darcy Donavan) as he shares his pet names for his genitalia: “I know what you’re asking yourself. The answer is yes. I have a nickname for my penis. It’s called the Octagon. But I also nicknamed my testes. My left one is James Westphal and my right one is Dr. Kenneth Noisewater. You ladies play your cards right, you just might get to meet the whole gang.” (In an alt for this scene, Brian shares that he has been to first base with forty‐three gals and has reached home base with four lucky ladies. Rudd thought that, for all of Brian’s explicit talk, he might actually be a virgin.)

Champ faces the camera and informs observers, “I’m all about having fun. You know, get a couple cocktails in me, start a fire in someone’s kitchen. Maybe go to SeaWorld, take my pants off.” (In a cut sequence, Champ stands on the roof and shouts, “Orgy!” at the assembled revelers. When he is greeted with dead silence, he apologizes for misreading the vibe.) Brick shows up patiently spooning mayonnaise into a toaster. “People seem to like me because I am polite, and I am rarely late. I like to eat ice cream and I really enjoy a nice pair of slacks.”

Cinematographer Tom Ackerman wanted to give Applegate a bit of 1930s‐style Hollywood glamour for her first appearance in the film. Ackerman had a soft spotlight fade up on Applegate, giving Veronica a faint glow. And when Ron first approaches Veronica and Applegate is seen in a close‐up, the shot is intended to dazzle. Ron tells Veronica, “You have an absolutely breathtaking hiney. I mean, that thing is good. I want to be friends with it.” The casually sexual, and sexist, tone was established moments earlier, when Ron was introduced by Brian to his blond friend, who pawed at her ample chest while purring in his direction, “I’ve got a big story for you, and it’s right here.” Ron, never one to not speak the words out loud, responded, “You pointed to your boobies.” Ron’s willingness to turn down this sure thing in pursuit of Veronica speaks to his romantic spirit, or to his egotism.

Ron is holding a festive drink with an oversized orange wedge and a small green umbrella plunked in its center, his lush patch of chest hair, exposed by his open orange robe, an ironic counterpoint to his statement of intent: “I don’t know how to put this, but I’m kind of a big deal.” Ron almost chuckles at having to mention the exceedingly obvious. “I’m very important. I have many leather‐bound books and my apartment smells of rich mahogany.” Veronica’s pause indicates she knows exactly who Ron is, even as she professes not to.

Ron instantly realizes he is overshooting his mark and asks Veronica if he can try again with her. “I want to say something. Want to put it out there. And if you like it, you can take it. If you don’t, send it right back.” He pauses before continuing. “I want to be on you.” When Veronica turns away, Ron repeats himself half‐heartedly, then takes a gloomy sip of his fruity beverage. The shoot ran so long that by the time of the last shot of the night, a two‐shot of Veronica and Ron, you could just make out the brightening sky behind the trees at the edges of the frame.

When the shoot paused at the end of the first week, Koechner, Rudd, and Carell went home and had identical conversations with their spouses. The new movie they were working on, they told their wives, was a dream, a hilarious script with a creative director. And the performers around them were each operating at the peak of their game. How could they possibly keep up when surrounded by such distinguished company? Everyone was better than they were — funnier, sharper, smarter.

The actors shared a three‐room trailer, and when shooting recommenced on Monday morning, they realized that each had spent the weekend roiling in the same discontent. It was a relief to discover that no one — except possibly the preternaturally self‐ possessed Will Ferrell — was immune to the fear of letting down a remarkably gifted ensemble.

The actors knew that something special was happening on set, facilitated by McKay, and did not want to do anything that would spoil it. Koechner thought of it as the comedy equivalent of a baseball milestone. If a pitcher was throwing a no‐hitter, his teammates would intentionally shy away from him, loath to say or do anything that would spoil the moment. The actors would gather in their shared trailer in the mornings until they were called to the set. They spent a good deal of their time mooning each other, with Rudd especially prone to yanking down his pants.

The most the actors would allow themselves were anodyne comments like “This feels pretty good, huh?” No one wanted to draw attention to what was taking place. But Carell and Rudd and the other actors would gather with the crew at lunchtime to watch the dailies, bearing heaping hot‐fudge sundaes as a postprandial treat as they watched the previous day’s action. Dailies were usually a chore for crew members, but this was notably different. The actors would have tears in their eyes from laughing so hard. The only thing Carell was worrying about was getting fat from all the sundaes.

From Kind of a Big Deal: How Anchorman Stayed Classy and Became the Most Iconic Comedy of the Twenty-First Century, by Saul Austerlitz, to be published on August 22, 2023 by Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Saul Austerlitz.