I used to love sleepovers at my grandma’s house because of her large television, premium-cable subscription, and vast collection of VHS tapes and DVDs. A movie that got a lot of time in her DVD/VHS combo player was A Goofy Movie, and of course its sequel, An Extremely Goofy Movie. I remember craving the overly drippy cheese pizza and crushing over both Roxanne and Powerline. Though I loved the movie, I never thought too deeply as to why until I saw a random Twitter thread years ago explaining how A Goofy Movie is actually about a Black man and his son. My jaw was on the floor. The people over at Vice picked up on the story too. It all made sense; my natural gravitation to the aesthetics, the familiarity of the energy, Tevin fucking Campbell … how did I not see it before?

Donald Glover pays homage to the movie that’s now considered a cult classic in this week’s Atlanta with a hilarious mockumentary-style episode that chronicles the making of “the Blackest movie of all time.” The entire thing plays out like a bit you take too far with friends after a smoking session: What if Disney made A Goofy Movie Black on purpose? What if a Black person made A Goofy Movie? What if a Black person was the CEO of Disney? Well, that’s exactly what happened in the Atlanta universe. We’re treated to a complete timeline of events that led to the beloved film, and eventually the beloved “Damn bitch, you live like this?” meme.

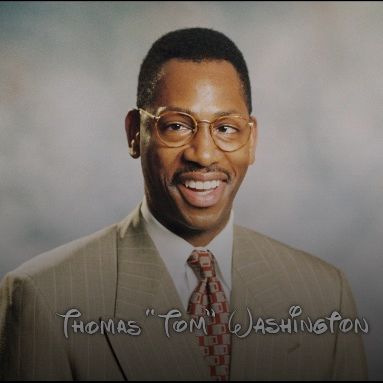

It’s the early ’90s and amid Disney’s resurgence due to the releases of The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and The Lion King, an early-career animator named Thomas Washington suddenly, and accidentally, becomes CEO of the company. Washington began working at Disney after a lifetime of drawing and getting his degree from Savannah College of Art and Design. He grew up obsessed with cartoons, and his talent and creativity, combined with the fact that he was one of the few Black students on campus, made him a standout. At SCAD he attended a speaking engagement led by Art Babbitt, the man who originated the Disney character Goofy. One of Washington’s previous teachers read a quote from a fictional article written by Babbitt that breaks down Goofy’s characterization: “Think of the Goof as a composite of an everlasting optimist, a gullible Good Samaritan, a half-wit, a shiftless, good-natured colored boy, and a hick …” The quote continues with pretty coded language about barbershops and laziness, but the point is, Goofy was created to mimic racist stereotypes about Black people.

Unfortunately, this isn’t a fictional account of how Goofy was created. I found an article published in 1996 that quotes the real Babbitt saying most of the above nonsense verbatim in a memo written in 1934. If you look closely at some of the older comics of Goofy, like in the clips shown in Atlanta’s mockumentary, it’s startlingly obvious that some of his actions have a racist undertone. (The watermelon was overkill.) Washington’s old professor goes on to say that his student developed an attachment to both Babbitt and Goofy, and that Babbitt’s quote became the basis for a series Washington called “Goofy, Please,” which depicted the Disney character as a Black man playing basketball. During his time at SCAD, he also created a short film based on his father’s death. The film was so poignant it landed him a job at Disney straight out of college as part of the company’s initiative to bring in diverse voices.

Washington’s position at Disney gave him a solid job and stability as he worked on one of the DuckTales movies. It was around this time that the 1992 L.A. riots broke out, an event that deeply impacted his life and inspired him to vow that if he ever did a movie for Disney, he wouldn’t hold back. As racial tensions rose in L.A. and across the country, Disney happened to lose its CEO due to ultimately fatal health complications. The executive board voted for Tom Washington — a man whose real name was Thompson Washington, not Thomas — thus installing a Black CEO due to a clerical error. Not wanting the optics of quickly hiring and firing a Black man, and being unable to sweep things under the rug because of Tom’s insistence that he is rightfully the CEO, Disney moved forward with the accidental decision.

A previous employee of Washington’s tells the cameras that on his first day as CEO, he showed a clip of Mickey Mouse, Goofy, and Pluto where Mickey is tugging on Pluto’s leash. Washington asked the room, “Why is Goofy letting Mickey do that? Goofy’s a dog and Pluto’s a dog, so why is he letting Mickey do that to one of his own?” Phew. He ran his entire tenure at Disney with this attitude; he knew his situation was precarious and it was inevitable his time at Disney would be short, so he set his sights on creating what he considered to be the Blackest film ever made. Washington enlisted fellow Black Disney animator Frank Rolls as director and pitched why Goofy was the perfect character for the project: He wanted to use Goofy’s story to highlight the systemic factors a lot of Black fathers deal with. Rolls was surprised by these thoughts coming from Washington, a man who he thought had a solid home life.

Washington married his wife, Annie, young and had one son, Maxwell, with her. He had a very close relationship with his son; scenes like Goofy and Max’s camping trip were inspired by Washington’s real relationship with his child. Maxwell describes some of the Easter eggs in A Goofy Movie that are direct winks at Black culture. The episode hits a stride here in terms of comedy as the mockumentary reaches to make A Goofy Movie seem a lot deeper than it is, comparing the road-trip map to The Negro Motorist Green Book or saying the movie confronted ideas around Black exceptionalism. It gets so ridiculous that one white employee describes hours of drawing until his fingers bled so he could get the Black dance moves just right for Washington.

The creation of A Goofy Movie snowballed into something so big it began to take over both Washington and the Disney offices. He would refer to Mickey Mouse as “this white boy” and ran a social club out of his office with the biggest Black stars in Hollywood (and Harrison Ford), giving us cameos from the legendary Sinbad and Brian McKnight contributing to the documentary.

Things started to spin out of control for Washington as the pressure of creating A Goofy Movie became too much. He started binge-drinking and cheating on his wife, leading to their eventual divorce and a rift between him and his son. When a Disney executive questioned if Washington was in control of the overinflated budget, he replied, “Of course I am! I’m Goofy,” letting out a demented Goofy “hyuck” laugh. They offered to buy him out to step down, but Washington refused. He started getting paranoid and aligned himself with numerous Black nationalist groups like the Nation of Islam and eventually with multiple gangs, promising shout-outs at the end of the movie. The ideas for the ending started getting really radical; Washington wanted Goofy and Max to get pulled over by a pig policeman in a scene that would end in … a shooting? Or Goofy could get shot at the Powerline concert for running onstage. Either way, someone’s getting shot. Oh, and he wanted Max and Goofy to stumble into a thrift store and find Huey Newton’s rattan throne, realizing the greater meaning of it all.

By the end of production of A Goofy Movie, Washington had a mental breakdown, recording a video of himself heavily inebriated, deeply depressed, and almost manic while crying on-camera repeating the phrase, “I’m so close,” and promising that this was all for the culture. Disney cut ties with Washington but still let him on the lot to see the final product of the movie. Replacing some of his more radical scenes, Disney watered down the concept to what we know A Goofy Movie to be today; instead of finding Newton’s chair, Max and Goofy find Bigfoot in the woods. This was the last straw for Washington, who drove off the lot only for his car to be found at the bottom of a lake 40 miles from Burbank — the same lake he went fishing with his son. They never found his body … but they did find his oversize white gloves.

Atlanta After Hours

• As hilarious as this episode was all around, I did see some parallels between Washington and Glover in terms of the internal struggle to “represent the culture.” It doesn’t help that a large chunk of Glover’s fan base is white. Even recapping the show can be difficult since sometimes it’s very clear that Black viewers and white viewers have drastically different experiences watching because of our different worldviews. For example, some white viewers didn’t understand why I, as well as Earn and Van, clocked the white man in the last episode as kind of creepy. This episode’s ideas about how A Goofy Movie is viewed through our lens as Black people is a great metaphor for how race informs how we consume media.

• When Rolls said that Washington wanted to address a plethora of issues in the Black community including fatherhood, gang violence, segregation, incarceration, and “the amount of cheese in African American diets,” I fell out. The cheese on those pizzas looked so good, it’s forever etched in my memory. What can I say? I’m a Black woman who loves cheese.

• The amount of care that was put into making this seem like a completely plausible documentary will not go unnoticed on my watch. There was the perfect amount of detail, nostalgia, and archival clips from real events and real cartoons. It stretches the absurdity at the perfect points, like finding the Goofy gloves and costume at the crime scene, but stays grounded in reality when necessary, as when drawing connections to real-life events including the riots, making the final product an excellent satire.