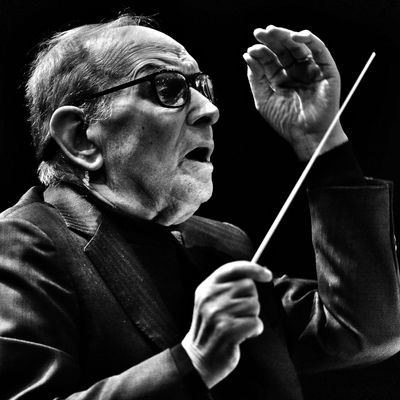

This article was originally posted in 2015. We’re republishing it in memory of Italian composer Ennio Morricone, who died on July 6, 2020 in Rome.

Quentin Tarantino’s Hateful Eight is the first time that the legendary composer Ennio Morricone has scored an entire movie for the spaghetti Western–loving director. (Indeed, it’s the first time any composer has scored an entire movie for Tarantino, who generally prefers his music repurposed.) Morricone, age 86, has continued to work fairly steadily, but it will be exciting for those of us who are fans of the composer to see the spotlight shine brightly on him once again. Because to say that Morricone is a great soundtrack composer — or even the greatest of all soundtrack composers — doesn’t quite do him justice. His influence is monumental across musical genres, and his innovations have been adopted even by avant-garde musicians. In fact, many people who’ve never seen a single film scored by the prolific Morricone can probably still easily identify many of his musical themes. Don’t believe me? Whistle a few tunes from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly or A Fistful of Dollars sometime, and you might find that even people who’ve never seen a frame of a spaghetti Western will know what you’re referencing.

In honor of the composer’s latest release, it seemed like a good time to go over his career and select some of his best musical cues — that is to say, the best pieces as they were used within the context of individual scenes in the films themselves. (Not every director always knew how to use Morricone’s music well.) Of course, this is a highly personal list — given the sheer size and diversity of the man’s output, any Morricone fan is sure to have individual pieces that resonate more for them than others. But here they are: Ennio Morricone’s 25 Greatest Musical Cues.

“Puck’s Lament,” Before the Revolution (1964)

In Bernardo Bertolucci’s breakthrough film, a young man from a well-off family struggles with his revolutionary ideals and the temptations of bourgeois life. In one of the film’s most achingly lovely scenes, a landowner named Puck laments the loss of the River Po and the natural beauty around him, provoking the ire of the young hero, who recognizes in this man many of the contradictions of his class. Bertolucci, not unlike Sergio Leone, keenly understood Morricone’s great strength: his ability to convey contradictory ideas through his music, in passages that could be both romantic and mocking, lyrical and playful.

“Opening Credits (Titoli),” A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

The desolate atmosphere of the first Sergio Leone–Ennio Morricone–Clint Eastwood spaghetti Western reflects both budget realities and the emptiness of its setting: a frightened, dying town, squeezed by rival murderous gangs, just waiting for a nameless loner to come and save it. And Morricone’s score for the film is often appropriately minimalist, utilizing Alessandro Alessandroni’s whistling, an echoing electric guitar, whip cracks, and those legendary choral blasts (“We can fight!”). It’s a hell of a thing, being a young kid and watching this movie come on the TV with that opening.

“The Final Duel,” A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

Though much of A Fistful of Dollars’ score is quite spare, for the final showdown, Morricone gives us something altogether more melodic and traditional. This ornate trumpet dirge popped up earlier in the film as well, but here, it fits perfectly — as the clouds of dynamite smoke and dust blow away to reveal Clint Eastwood’s character, seemingly back from the dead to exact retribution on Ramon Rojo and his gang. This has become established as one of Morricone’s signature pieces, which is somewhat ironic, as it’s also an homage to Dimitri Tiomkin’s score for Howard Hawks’s John Wayne Western Rio Bravo.

“Sixty Seconds to What,” For a Few Dollars More (1965)

A musical pocket watch is a recurring element in Sergio Leone’s second film in the Man With No Name trilogy, and hearing the many uses Morricone puts it to musically is one of the film’s many pleasures. The watch itself is an object that unites one of the good guys (played by Lee Van Cleef) with the villain, the deranged bandit Indio (played by Gian-Maria Volonté). The final showdown, with its dueling watches, plays with our anticipation beautifully; we’ve heard the watch’s tune before and think we know exactly when it’s going to end. Also note how the tune changes slightly whenever it’s played in the film — reflecting the characters’ inner states.

“Opening Credits,” Hawks and the Sparrows (1966)

Pier Paolo Pasolini’s comic allegory about politics and religion features one of the strangest and most unforgettable opening-credits sequences ever. The credits are sung in a mock-heroic and quite catchy tune — one that puts the viewer in the perfect state of mind to accept a movie featuring Marxist theory, toilet humor, footage of a real political funeral, an interlude about St. Francis, and a talking Communist crow.

“The End,” The Battle of Algiers (1966)

Gillo Pontecorvo’s masterpiece is one of the most resilient films ever made. A documentary-style portrait of the Algerian conflict, it’s been embraced over the years by colonialists, freedom-fighters, police forces, occupying armies, and terrorists (not to mention film buffs). Part of the film’s enduring appeal has to be Morricone’s innovative, unsettling score. Nowhere is his approach more evident than at the very end, where we watch a chaotic protest to the accompaniment first of thundering, warlike drums — which we’ve heard throughout the film, often during bombings — and waves of high-pitched electronic ululations. Then, briefly, we hear two lovely phrases of an orderly, sad harpsichord theme, which is followed immediately, right as we fade to black, by a jagged little repeated motif in a minor key. Unstable and questioning, it sends us out on an uncertain and disturbing note.

“An Axe in the Head,” Navajo Joe (1966)

Morricone’s score to this Burt Reynolds–starring Western directed by Sergio Corbucci is one of his most repurposed. (Even Alexander Payne used it in Election.) Understandably so: With its bold combination of wails, rolling piano, and howling drums, it’s truly primal — at least until the guitar, choir, and orchestra kick in, at which point it becomes downright mythic. The score’s most common motif is repeated throughout: We first hear it right at the beginning, as we see Joe’s wife killed and scalped by the villains, so that when it comes back, right here at the end, we feel some of Joe’s own bloodlust and vengeance.

“The Chase,” The Big Gundown (1966)

Here’s one whose clip I couldn’t find on YouTube, though at least the piece itself is there. Morricone’s score for Sergio Sollima’s Western — which stars Lee Van Cleef as a stoic lawman and Tomas Milian as the knife-throwing bandit Cuchillo, whom he first chases, then joins forces with — is justifiably famous, as it’s one of the composer’s most moving and explosive works. There are several notable pieces from this soundtrack, but this one, which plays during a third-act chase, is one of Morricone’s finest actual cues.

“The Ecstasy of Gold,” The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

One of Morricone’s most famous pieces — Metallica has used it for its concert intros — this lengthy, unforgettable, driving orchestral and choral freakout is a perfect example of the Leone-Morricone collaboration. Who else but those two would give so much screen time just to shots of Eli Wallach running through a cemetery, extended to the point of abstraction? Leone knows at this moment that the music is the real star, and he lets Morricone carry the day.

“The Trio,” The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

Though it’s sometimes upstaged by the “Ecstasy of Gold”–soundtracked run through the cemetery that precedes it, the final showdown in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly also features some of Morricone’s finest, most complex work. Listen to this one all the way through, as the beautiful trumpet solos and clacking castanets give way about halfway through to something altogether more experimental, atonal, and synthesized. Are those meant to be futuristic gunshots, maybe anticipating the gunfire to come? And are those other sounds meant to sound like space-age water droplets, highlighting the sweat on the actors’ faces? (Am I overthinking this? Yes!) It’s as if the score gets deconstructed halfway through — along with the images, as the camera gets closer to the actors and the editing becomes more fragmentary — before building back to a thundering, rolling crescendo. And then, after all that … the damn thing cuts out before the music finishes, as Clint Eastwood shoots Lee Van Cleef and Eli Wallach discovers his gun has no bullets.

“The Nightclub Scene,” Danger: Diabolik (1968)

Mario Bava’s zonked-out spoof of James Bond–style antics is one of the strangest films I’ve ever seen, and Morricone’s score for it is a great time capsule of ‘60s-isms. This scene, set in a drug-drenched nightclub — filled with faux funk, fuzzy distortion, tambourines, and chanting to go with all the young people tripping out — gives you a good idea of what the rest of the film is like. Morricone’s work here is beautiful, albeit in a daft way: It’s like a pop song composed by someone who has only read descriptions of pop songs.

“Jill’s Arrival,” Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

After the Man With No Name trilogy, Leone and Morricone collaborated on what would be one of the most ambitious Westerns ever. This time, Morricone composed the score beforehand, so that Leone would play tapes of his music on set both to get the actors into the scene and to time his camera movements. This sublime scene shows the fruits of that approach. In it, Claudia Cardinale’s Jill stands by herself in a train station, waiting for someone to come meet her. As she begins to realize that nobody’s coming, we hear a melancholy, solo female singer on the soundtrack. Then Jill enters the station house, the music begins to swell, and the camera cranes up and over the roof … so that we see, on the other side, a bustling, almost dreamlike vision of the American West. And then, the ambient sound of people and carts and horses, curiously absent until now, suddenly comes charging into the soundtrack.

“Frank’s Introduction,” Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

The sound of rushed footsteps, the POV tracking shot, cutting to that sudden close-up, timed to that sudden, distorted, echoing chord. (Could that be the single greatest movie music cue ever?) We watch this kid (whom we’ve never met, and never will) look around and realize that his entire family has been gunned down. And then these grim, dusty figures emerge out of the shrubs as the wailing harmonica merges with the howling wind. They look like they’re from another world — which they are, since this moment perfectly encapsulates the Western’s classic theme of civilization versus savagery. And then the final, perfect coup de grâce: The camera dollies around the figure leading the men to reveal that Henry Fonda — Henry Fonda! American cinema’s paragon of decency and moral authority! — is the monster at the center of this slaughter.

“Opening Titles,” The Bird With the Crystal Plumage (1970)

In Dario Argento’s seminal 1970 giallo thriller, Morricone’s lullabylike theme accompanies the intensely creepy stalking of the film’s first victim in the kind of juxtaposition that horror movies have been milking for years. These are the opening passages of one of Morricone’s most lush scores, but the full piece itself doesn’t play out until the very end, nicely bracketing the film. Morricone scored numerous giallo thrillers in his career, and while his scores for these films aren’t as well-known as some of his spaghetti Western themes, they’re often quite disturbing and avant-garde in their own right.

“Vamos a Matar, Compañeros,” Compañeros (1970)

In Sergio Corbucci’s wild Zapata Western, rebel peasant Tomas Milian and Swedish mercenary Franco Nero have to join forces during the Mexican Revolution. It’s one of those spaghetti Westerns where characters from wildly different backgrounds are forced together by war and revolution, and Morricone’s cacophonic, chaotic, and boisterous score reflects that. Particularly the film’s main theme, “Vamos a matar, compañeros” (“Let’s go and kill, comrades”), which plays here at the end, as Nero’s reserved, methodical loner lets loose one last bellow as he decides to rejoin the fight with his comrades.

“Hope of Freedom,” Sacco & Vanzetti (1971)

Giuliano Montaldo’s tender, haunting tale about the two Italian immigrants and anarchists who were arrested and executed for murder in Massachusetts in 1927 features a couple of Morricone’s best-known songs: “Here’s to You” and “The Ballad of Sacco and Vanzetti,” both sung by Joan Baez. But it also features this lyrical interlude near the end of the film, as Vanzetti tries to convince Sacco to look through the bars of the prison car transporting them from their trial, where they’ve just been sentenced to death. Surprisingly, the film’s score is quite spare, and Morricone holds his fire for much of the time — which just heightens the power of moments like these.

“Here’s to You (End Credits),” Sacco & Vanzetti (1971)

Of course, no Morricone list would be complete without this Joan Baez collaboration. But look at how well it’s arranged and used: As the headstrong Vanzetti briskly sits in the electric chair, a funereal organ starts up, and then, as soon as he’s pronounced dead (over a fully black screen), this rousing folk song suddenly barges in, as if the character has effectively passed over into myth. It’s a great way to end one of the most depressing movies ever made.

“The Dance of Anger,” Allonsànfan (1974)

Most viewers are probably familiar with this theme from its repurposing in Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds, but it’s worth seeking out the Taviani Brothers film from which it hails, as it’s a near-masterpiece. Allonsànfan is a sober but stylized look at a 19th-century revolutionary (Marcello Mastroianni) from a wealthy family who is torn between his ideals, his former comrades, his love for his son, and the comforts of a happy, quiet life. Like many films by the Tavianis, it mixes fablelike simplicity with passages of surreal beauty — never more so than in this scene near the end where the upbeat, rhythmic music gives way to a weirdly ominous, foot-stomping dance.

“The Revolution,” 1900 (1976)

For Bernardo Bertolucci’s insanely ambitious, star-studded pastoral Marxist epic, Morricone composed one of his most lovely and resonant melodies. Bertolucci opens his film with scenes from Italy’s Day of Liberation in 1945, showing the peasants’ uprising against the landowners. But then he flashes back and tells a story that spans many decades, portraying the beginnings of class-consciousness, socialism, and fascism in the Emilia-Romagna region. By the time we revisit these scenes near the end of the film, these peasants have gained a noble aura, visually and sonically. But the music also has to play a subtle role here, because what Bertolucci is depicting isn’t what actually happened in 1945; it’s an idealized version of it. This is a historical film that becomes a fantasy, and Morricone’s music brilliantly reflects that.

“The Locust Swarm,” Days of Heaven (1978)

Morricone and Terrence Malick famously did not get along on this film — the composer thought the enigmatic director didn’t understand soundtrack music at all. But somehow, their collaboration worked. This score may well be one of Morricone’s greatest, most romantic works. (Even if he has to share part of the credit with Camille Saint-Saëns, whose “Carnival of the Animals” is also used so effectively by Malick.) But perhaps its high point is the climactic plague of locusts that descends near the film’s end, turning this Edenic Texas farm into a fiery hellscape of jealousy and retribution. Morricone’s dissonant music, with its sharp, discordant strings and rattling pianos, works in tandem with the sound effects and the snatches of screamed dialogue to create an effect that feels unreal and out of control.

“Cockeye’s Death,” Once Upon a Time in America (1984)

“Noodles, I slipped.” Leone’s massive final film is now considered a masterpiece, but it wasn’t nearly so well- received when it first came out, in part because audiences in the 1980s didn’t know what to do with its mix of grim gangster epic and moments of intense melodrama. Take this early scene, a harrowing, nakedly emotional moment where our heroes, a group of Brooklyn toughs growing up in the 1920s and ‘30s, lose one of their own. Watch and listen to how the lone pan flute (played by the great Gheorghe Zamfir) matches the lone boy left out in the open, unable to hide while his friends take cover. Is it manipulative? Sure. But even if you try to resist it, this is the kind of scene that will expertly jerk tears out of you.

“Mendoza’s Penance,” The Mission (1986)

Roland Joffe’s 1986 epic, which follows the struggle of a small group of Jesuits in a Guarani community against Spanish and Portuguese colonists, is, in its own way, as much about music as it is about religion or history: Jeremy Irons’s Father Gabriel and the natives initially connect through an oboe, and religious music plays a key role throughout. But perhaps the film’s most powerful cue comes in its most powerful scene. A repentant slaver and soldier, played by Robert De Niro, drags his armor and weapons up a mountain as a means of penance. The Indians know him, and they’re initially fearful and suspicious. But then one man approaches De Niro and cuts away his heavy load. It’s a moment of intense, overwhelming humanity, perfectly highlighted by Morricone’s lilting score.

“Ambush on the Bridge,” The Untouchables (1987)

For Brian De Palma’s 1987 hit, in which Kevin Costner’s title team of do-gooders tried to take down Robert De Niro’s Al Capone, Morricone created a brassy, busy score, which is at times deployed in mischievous fashion. Here, in one of the Untouchables crew’s early successes, as they raid a liquor-smuggling operation on the Canadian border, the film briefly starts to resemble a Western. The music is stirring, but it sort of undercuts the action, too; there’s a surreal quality to the broadness of the heroism on display, like we secretly know it can’t last.

“The Kissing Montage,” Cinema Paradiso (1988)

At the end of Giuseppe Tornatore’s beloved Oscar-winning film, the grown-up Salvatore, who was once a projectionist’s assistant in his small town’s cinema, sits down to watch a mysterious reel of film gifted to him by the now-deceased older projectionist. The footage, it turns out, is a montage of all the kissing scenes the projectionist was forced to take out over the years under the watchful eye of the local priest. Morricone’s music here, one of his most famous, surges with both wonder and regret.

“Dallas Recalled,” In the Line of Fire (1993)

Morricone reunited with Eastwood for this great Wolfgang Petersen thriller about an aging Secret Service agent trying to hunt down an assassin (John Malkovich) threatening to kill the president of the United States. It’s a great thriller, but it’s also a surprisingly somber, reflective one. Here, in one of the film’s quiet moments, Eastwood’s character recalls to fellow agent Rene Russo that day in November 1963 when he failed to save the life of John F. Kennedy. It’s absolutely one of the actor’s greatest performances. But it’s even more than that: As his character looks back, to the strains of Morricone’s tense, melancholy score, Eastwood sheds any and all pretense, and we suddenly feel like we’re watching the man himself, looking back on his own life — and even he seems surprised by the fact that he’s about to cry.