Horror is particularly good at building bridges. Sharing what scares us — whether that’s zombies, ghosts, aging, or being left behind — helps us understand each other better. The best horror books of 2024 are the ones that feel like a primal scream, a demand to be seen and recognized. From catharsis to revenge, from cannibalism to slashers, from vampires to giant bugs, here are the horror books that stood out this year.

All books are listed by publishing date, starting with the latest releases.

American Rapture, by C.J. Leede

Sophie has been raised in a severely conservative Catholic community, kept cloistered by her parents, terrified of sin and sex and the secular world. So when a plague starts to spread — one that turns sexual desire into something ugly and violent — she’s profoundly unprepared. Nevertheless, she sets out across a hellish vision of Wisconsin to find her brother, assembling a motley crew of survivors along the way, all the while navigating her own newly awakened sexuality. Though Sophie is a teenager, this is not a young-adult book. The themes here — Christofascism, sexuality, shame, moral panics — are heady, the book is brutally violent, and, as with her previous novel, Maeve Fly, Leede doesn’t pull a single punch. It’s also touching, and funny, and sad — I sobbed straight through the last 50 pages.

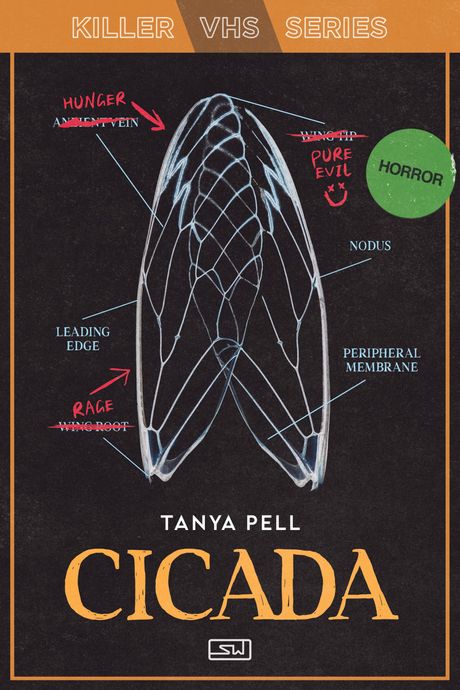

Cicada, by Tanya Pell

By the time Ash starts to realize that her boyfriend, Richie, really sucks, they’re stuck in rural Mississippi on a detour from the road trip from hell. In a small town, they discover an oddball film festival for CICADA, a found-footage cult-classic creature feature filmed there years before. But something’s off — the townsfolk are a little intense, and nobody seems to want to let them leave. And then, of course, the killings begin. Turns out that found-footage movie was more like a documentary. Ash is a delightful lead, full of piss and vinegar — a final girl, yes, but an active and resourceful one whose primary mode is Deeply Irritated. Richie immediately and decisively enters the Bad Horror Boyfriends Hall of Fame, and the eponymous monster is deliciously disgusting.

A Sunny Place for Shady People, by Mariana Enriquez

The stories in Mariana Enriquez’s newest collection share thematic DNA with her two previous collections: They’re about Argentina in the wake of the junta, about the lives of women and families, about generational trauma, and, always, about the familiar made strange and hostile. But there’s no such thing as a boring Mariana Enriquez story. Standouts here include “Black Eyes,” about NGO employees serving food to the homeless who are haunted by two uncanny children; “Hyena Hymns,” in which a vacationing couple explore an abandoned building formerly used for torture and detention; and the title story, about an Argentinian journalist reporting on a cult that has grown up around the real-life disappearance and death of Elisa Lam at a Los Angeles hotel in 2013. With A Sunny Place for Shady People, Enriquez demonstrates yet again why she’s an undisputed master of short horror.

So Thirsty, by Rachel Harrison

It’s Sloane’s birthday weekend, and her distant husband has booked her a getaway with her wild child best friend Naomi. When Naomi, true to form, finagles an invite to a house party thrown by some mysterious European strangers, though, things take a turn for the sexy, and then the bloody. Before long, both women have crossed a rubicon, and their lives will never be the same. There’s no one else currently working in horror who writes about women (particularly women’s friendships) the way Rachel Harrison does — her characters are so real and flawed and lovable you could almost pick up the phone and call them. So Thirsty is a millennial Thelma & Louise with vampires, a story about friendship, aging, and agency, and it goes down like cold water on a hot day.

Sacrificial Animals, by Kailee Pedersen

When Carlyle Morrow summons his estranged sons, Nick and Joshua, home for a deathbed reunion, Nick doesn’t expect his sister-in-law Emilia to join — after all, Carlyle disowned Joshua years before for the crime of marrying an Asian woman. But soon enough, all three have arrived at the Morrow estate in rural Nebraska, where the aftereffects of Carlyle’s cruel, domineering parenting still echo. Joshua, always the favored son, reconnects with Carlyle immediately, leaving Nick and Emilia at loose ends. Emilia keeps her own counsel, but it’s clear she has an agenda. Pedersen, who was herself adopted from China by a Nebraskan family, conjures a starkly beautiful vision of the Plains reminiscent of David Wroblewski’s The Story of Edgar Sawtelle. It’s a remarkable debut, a striking blend of American frontier stoicism and Chinese folklore.

House of Bone and Rain, by Gabino Iglesias

Set during and immediately after Hurricane Maria, the 2017 storm that devastated Puerto Rico, House of Bone and Rain is the story of five friends on the precipice between adolescence and adulthood. When one of their mothers is murdered outside the club where she works, they vow revenge against her killer, a fearsome drug lord — but the storm is coming, and with it, nameless evils. Iglesias makes Old San Juan come alive on the page — it’s colorful, humid, rundown, and vital all at once — and the relationships between the main characters vibrate with loyalty, friction, and frustration. It’s a touching and terrifying story with a cosmic horror twist. There’s a refrain in the novel that serves as a mission statement for horror fiction in general as much as it does for this specific book: “Todas las historias son historias de fantasmas.” All stories are ghost stories.

I Was a Teenage Slasher, by Stephan Graham Jones

Stephen Graham Jones is horror literature’s slasher maestro. I Was a Teenage Slasher comes hot on the heels of the conclusion of Jones’ meta-slasher Indian Lake trilogy (and I do mean hot — The Angel of Indian Lake came out in March of this year), and introduces us to a very different kind of killer. It’s 1989 in dusty west Texas, and Tolly Driver is having a bad night. He’s gotten embarrassingly drunk at a house party, nearly died from an allergic reaction to an errant peanut, and — don’t you hate it when this happens? — incurred a curse that dooms him to kill for revenge. It’s a slasher novel with a paranormal twist, narrated by the slasher (the Tolly of middle age, reflecting on the year that defined and derailed his life). It’s hard enough to reinvent such a thoroughly-explored subgenre, let alone to do so twice in the same year. But Jones makes it look effortless. His idiosyncratic narrative style, conversational and discursive, may take a little getting used to if you haven’t read him before, but he’s a singular talent — the sensitively-shaded contrast between present-day Tolly and teenage Tolly alone is worth the price of admission here.

The Eyes Are the Best Part, by Monika Kim

College-age Ji-won and her younger sister, Ji-hyun, are left to pick up the pieces while their mother grieves the end of her marriage in the wake of her husband’s infidelity. But then their Umma brings home a new boyfriend, George, a walking microaggression who can’t keep his roving eyes off any Asian woman he sees. And then Ji-won starts having dreams of eyeballs — beautiful blue eyes, just like George’s. And they make her hungry. Kim’s gut-churning debut is a sharp, sly commentary on the fetishization of Asian women, particularly how it feels to be on the receiving end. Ji-won is an engaging antiheroine, a vivid portrait of the way rage can curdle when it doesn’t have an outlet. It’s a perfect blend of high and low, of message and (sometimes literal) pulp entertainment, grounded by elements like the lived-in relationship between Ji-won and Ji-hyun.

Cuckoo, by Gretchen Felker-Martin

Felker-Martin’s new novel is equal parts IT, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and The Thing, but queerer, nastier, and gooier than all three of those stories combined. Cuckoo begins in the ’90s, when a handful of queer and trans teens are ripped from their families and shipped off to a conversion camp in the desert, where they’re subject to abuse and made to perform hard labor under inhumane conditions. Naturally, there’s something much darker going on at Camp Resolution — something that explains why the kids who “graduate” from the camp go back to their families a little … different. As with Tilman Singer’s unrelated 2024 horror movie of the same name, the title is a clue, but even that knowledge can’t prepare you for what waits beneath Camp Resolution. Felker-Martin has a real talent for sensory detail on the page, which she applies to everything from jewel-like hummingbirds in lush gardens to the roiling, weeping flesh of an alien monstrosity. But the thing that truly sets her writing apart is anger: Cuckoo is full of barely restrained rage at the world’s treatment of queer and trans youths, and at the unutterable betrayal of a parent sending their child to a place like Camp Resolution. (The book’s dedication reads, simply, “For all unwanted children.”)

The Z Word, by Lindsay King-Miller

Breakups are hard. Breakups in a small town where you have to run into your ex all the time? Even harder. Breakups during a zombie outbreak over Pride weekend? Now that’s a nightmare. Wendy, newly single, is trying to navigate Pride in her adopted home of San Lazaro, Arizona. But when the violence begins, Wendy has to fight for survival, relying on her own wits and a ragtag queer found family — which, of course, includes her ex, Leah. King-Miller’s debut novel is firing on all cylinders: There’s heartbreak, laugh-out-loud moments, some very hot sex, and a couple truly devastating deaths (an interstitial chapter narrated by a peripheral character as they succumb to the infection moved me to tears). There’s even a nonbinary stoner pizza-delivery person named Sunshine. The Z Word tackles corporations at pride, rainbow-washing, hard seltzer, queer drama, sword lesbians, and so much more.