Do you remember where you were when Elvis died? When John Lennon was murdered? When you got the news about Prince? David Bowie? Kurt Cobain? Lux Interior? The Ramones? Chuck Berry?

I was in my car when I got the news yesterday that Charlie Watts had died. Half a second earlier, I was marveling at the cowbell part on an oddball New Orleans R&B single, a sort of half-mambo and a marvel of Afro-Cuban rhythm, the kind of thing that dazzles me and, aside from the nominative topic of the book, inspired me to write Sympathy for the Drummer: Why Charlie Watts Matters. Charlie knew that swing was always the thing, and while there are a million ways to do it right, there are a million guys who are never going to come remotely close. It’s like pizza — so few ingredients, and yet there are still a lot of people who fuck it up. Charlie Watts could be the guy on the pizza box saying, “You’ve tried the rest, now try the best.” And that could just as well be his bio, or at least the origin story: a jazz drummer who could swing a battleship, and who was more or less slumming it when he joined the Rolling Stones, but instantly catapulted them from basement blues clubs to the big time. That was in 1963.

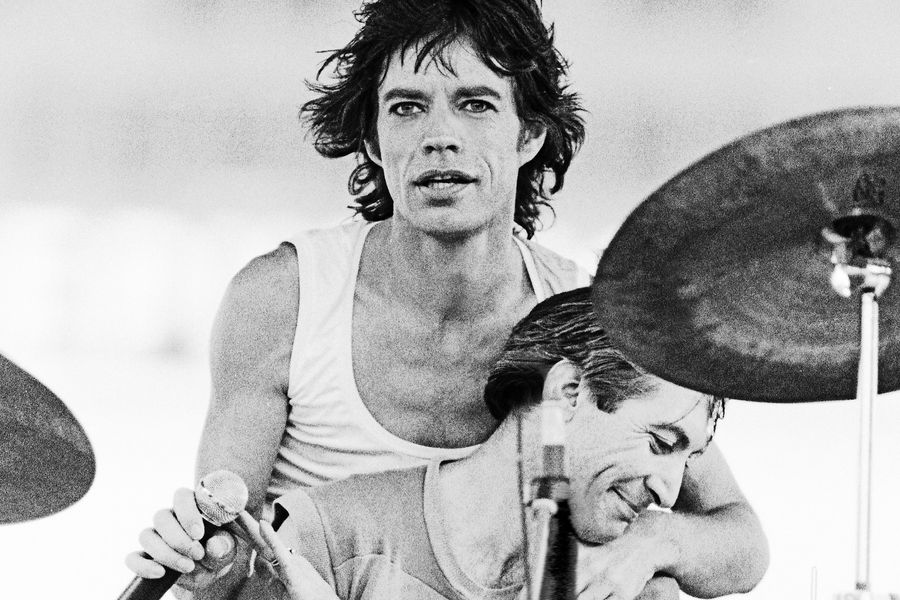

The Rolling Stones were smart to hire a cat who would always put the roll in front of the rock. In the somewhat less-than-elegant equation of rock and roll, the most important part of the equation — as in love and sex — the roll is key. Therein lies the swing, the seduction, the grease for the engine; roll is anticipation, rock is penetration. Any dunce can rock. Children rock. Horny teenagers rock. Metallica rocks. Charlie Watts rolled. And as much as he was a mereological essential to their sound, he was more than that — cast not only as the drummer in the Greatest Rock and Roll Band in the World, but something like the straight man in a British sitcom, the sympathetic glue between the druggy, heavily armed, piratelike guitar player and the gender-bending lead singer. He mattered, especially so when it didn’t seem that way.

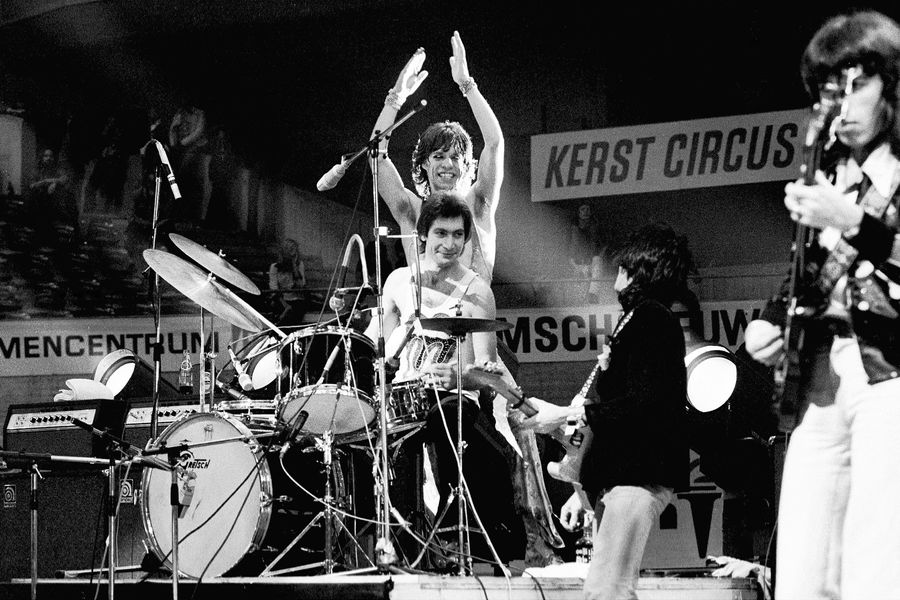

Right now, though, I thought I’d tell you the story everyone loves to hear, about the night Charlie slugged Mick Jagger in the jaw at a hotel in Amsterdam in 1984. It strikes me as odd, that after decades of playing the drums for the Rolling Stones, this is the story everyone loves to tell? Is it because it speaks truth to power? I think everyone likes to hear that the world’s most urbane drummer, an accidental rock star with a reputation as an old-school gentleman, was not to be fucked with. But no one seems to ever remember the punch line, so wait for it. And then maybe come over to my house and watch Ladies and Gentlemen: The Rolling Stones with me. Bring some Jack Daniels and a handkerchief. I’m going to need one.

This is the most famous Charlie Watts story. It is a very good story, and true — you cannot beat the Charlie Watts right hook. It’s like being hit by a freight train. Think about him playing “Rip This Joint” on the side of your skull, and you begin to get the idea.

These were bad times for the Rolling Stones. Keith had finally gotten clean, and while Mick had been doing a championship job holding things together with a world-class junkie as his second, by the time they come out the other side, he is convinced the Rolling Stones are his band, and the last thing in the world he wants is to cede control to a cleaned-up junkie guitar player now capable of sharing the decision making. What’s more, heels are dug deep into the argument that will define the confusion of their work for years: Mick wants to make a trendy pop record heavy on dance music, and Keith wants to stick to their roots and drive the guitars into the earth. Blues, reggae, rock’n’roll, whatever, just no tricks. He doesn’t care what the kids are listening to — he cares about what the Rolling Stones do best. The situation only gets worse when Mick decides he needs a solo career.

Mick had negotiated a new recording contract for the Rolling Stones, and somehow came out of it with a huge deal for himself, to do a pile of solo records for scads of dough, and World War III ensues. It was all done in the middle of the night, when no one was watching, and that’s not how shit goes down in this cosa nostra. As anyone who has ever seen Goodfellas knows, “You had to have a sit-down, and you better get an okay, or you’d be the one who got whacked.”

Keith sees this as something far beyond sedition. It is mendacious, dishonest, and disrespectful, a knife in the fucking back. No one is bigger than the band. They built this thing of theirs together, and now Keith feels betrayed, and Charlie, whose sense of loyalty to the band is as deep as the ocean, feels worse than Keith. This according to Keith, who is on a homicidal rampage.

Everyone has had it with Mick, who has gone rogue in his bid to become the next Michael Jackson or David Bowie. He especially worshipped David Bowie, who moved easily between worlds as a professional weirdo, international fashion icon (more like interstellar fashion icon), rock-star royalty, and could have massive dance hits and still be respected as a legit artiste.

It was a hardcore crush, the Jagger/Bowie thing. Where do you think Mick got the idea for all that gender-bending in the early 1970s? Of course, unlike Bowie, Mick was no avant-gardist — he had none of the cultural fearlessness of Bowie, and he was way too obsessed with being on trend to experiment—not to mention, his brand was the Rolling Stones. Somehow, Mick saw this not as the greatest blessing ever bestowed upon a former economics student but “a millstone around his neck,” as he snarked to a British tabloid just around the time he was releasing his first solo record and getting ready to tour with a band of mercenaries.

Keith went berserk when he heard that comment: “Disco boy, Jagger’s Little Jerk Off Band, why doesn’t he join Aerosmith?” Keith was never one to pull punches. Neither was Charlie. By 1984, the Stones are not getting along at all, but they’re trying to patch things up, and they find themselves in Amsterdam for a meeting. Mick and Keith are still on lousy terms, but they decide to go out for a few — a few being Mick’s limit. Anyway, Keith lends Mick a jacket to go out, not incidentally the one Keith got married in, and they get back to the hotel around five in the morning, properly potted. At which point Mick has the bright idea, against Keith’s sage advice, to call up to Charlie’s room and demand, “Where’s my drummer?”

According to Keith, “Twenty minutes later, there was a knock at the door. There was Charlie Watts, Savile Row suit, perfectly dressed, tie, shaved, the whole fucking bit. I could smell the cologne! I opened the door and he didn’t even look at me, he walked straight past me, got a hold of Mick and said, ‘Never call me your drummer again.’ Then he hauled him up by the lapels of my jacket and gave him a right hook.”

Keith calls it the “drummer’s punch” and says “it’s lethal; it carries a lot of balance and timing.” Nothing less than you would expect from a guy whose right hand has been carrying the weight of The Greatest Rock’n’roll Band in the World for 20 years.

So far, so good. But here’s the part everyone forgets: the Charlie Watts right hook is in fact no laughing matter, and Mick flies back onto a platter of smoked salmon and begins to slide out the open window toward the canal below — and admit it, Mick Jagger sliding out a window on a platter of smoked fish into a canal is fucking hilarious. After all the drugs, the misadventure, Altamont, and every other fucked-up situation that they have ever been in, who thought this is how the Rolling Stones would end, in a scene more worthy of a Marx Brothers movie than Cocksucker Blues?

Except that Keith realizes that Mick is wearing his jacket, the one he got married in, and he really wants it back. It’s a real “leave the gun, take the cannoli” moment. Keith grabs Mick and hauls him back into the room. Charlie is incensed — he was happy to see Mick go flying out the window. In fact, he wants to have another go at it, but Keith is insistent about not wanting to lose the jacket.

Saving Mick’s life, oddly, does not improve things. Keith, that sentimental fool, continues his rampage against Mick, whom he now regularly refers to as “Brenda,” or “Madam,” or “Her Majesty.” He’s had it. His basic outrage is that if Mick wanted to make a record of Irish lullabies with Liberace — something he couldn’t have done with the Stones — well then, have at it, but “if he doesn’t want to go out with the Stones and then goes out with Schmuck and Ball’s band instead, I’ll slit his fucking throat.” It’s a low moment for the Stones, but you couldn’t say it didn’t make for good copy. Someone asked Keith, “When are you two going to stop bitching at each other?” and Keith’s response was, “Ask the bitch.”

There was a huge amount of publicity surrounding Mick’s first solo record, She’s the Boss, but as a wise man once said, “For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?” Another wise man, namely Keith, said, “It’s like Mein Kampf. Everybody had a copy, but nobody listened to it.” But the harm is done — for the next few years, the Rolling Stones are effectively doing their best impression of Schrödinger’s cat, and Keith is in murder mode.

But back to our hero. The remarkable thing — or perhaps the most unsurprising thing — is that Charlie Watts is the only Rolling Stone who could make a run of perfectly lovely solo records that are beyond criticism. He might as well be doing the record of lullabies with Liberace — that’s the genius of Charlie Watts. There is no agenda. Ars gratia artis — he’s doing it because he loves it. It is pure of spirit in every possible way.

When his jazz combo the Charlie Watts Quintet became a working reality, between Stones tours in the early 1990s, Charlie started showing up on television, seemingly out of character for “the quiet Stone.” Famously press-shy, he was never game to talk about his steady gig, but he felt like he had to go old-school with his jazz bands and get the word out. He had the same reasonable fear as any other jazz musician in the latter part of the 20th century — that the only people in the audience on any given night might be his wife and his best mate. But he was treated with godlike reverence, even as he disarmed talk-show hosts with his good manners, dry wit, and refusal to talk about the Rolling Stones.

Let’s be very honest here: With few exceptions, what chance does a jazz musician have of getting to play on a mainstream talk show, let alone sit on the couch for the interview? Being a Rolling Stone has its perks — you just didn’t realize until now that it meant bringing your jazz band on to late night television.

As it turned out, Charlie Watts, sans Stones, was adored — the mystique of being the one guy in the group who didn’t spend his entire allowance on eyeliner, who was genuinely shy, whose threads spoke to gentility and not decadence, and who played the drums with a humility that would have been unnerving if it weren’t so fucking suave (he was also an inveterate, old-school stick twirler), was, in its own urbane way, a very powerful thing.

Charlie Watts playing the drums is the sound of happiness, the aural equivalent of Snoopy doing his dance of joy. It came from his heart, not from his hands. And no drum solos! Not because he wasn’t good enough to play them, but because he was good enough not to have to.

In many ways, the Rolling Stones at their best were a more intense jazz band than Charlie’s actual jazz bands — he played more aggressive, out-there jazz in the first four bars of “All Down the Line” and the breakdowns of “Rip This Joint” than with any of his traditional jazz combos. There was more improvising and flashing of chops in “Midnight Rambler,” when things were going right and Keith and Charlie were doing that thing, changing tempos and mashing up crazy shuffle stops, than there were on any Quintet session. Duke Ellington, as is often the case, said it best: “Rock ’n’ roll is the most raucous form of jazz.” And this is just one more reason Why Charlie Watts Matters: Even being in the world’s most successful rock’n’roll band could not stop him from living his dream.

Excerpted from the book Sympathy for the Drummer: Why Charlie Watts Matters by Mike Edison. Copyright © 2019 by Mike Edison. From Backbeat Books, an imprint of the Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. Reprinted by permission.

More on Charlie Watts

- Charlie Watts’s Final Gift Was a Rolling Stones Succession Plan

- The Rock Hall Induction Cut a Charlie Watts All-Star Tribute for Time

- This Previously Unheard Rolling Stones Song Should’ve Made the Tattoo You Cut