This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

It was 2015 in New York City. Hamilton was on Broadway, Donald Trump was hosting Saturday Night Live, and, at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, a fresh crop of comedy kids was striving to become fuck-you famous. The key, as historically proved by their forebears, was making it into one of the highly competitive on-campus sketch, improv, or stand-up groups — ideally Hammerkatz or Dangerbox or Astor Place Riots — and riding those waves to their seemingly inevitable destinations: Saturday Night Live; Comedy Central; a series on FX or the CW or HBO.

Rachel Sennott, a freshman acting student, and Ayo Edebiri, a sophomore teaching student (who’d soon switch to dramatic writing), first passed each other in the hallway after one of their auditions. Neither got into any of the groups, a fate that at the time felt like the doors at 30 Rock were preemptively slamming in their faces. (Indeed, some of their peers who did get in ended up exactly where they thought they’d be: SNL hired the Please Don’t Destroy boys, a sketch-comedy group comprised of NYU alums Ben Marshall, John Higgins, and Martin Herlihy.) Shortly thereafter, Edebiri noticed Sennott at a party on a friend’s roof, drunkenly ranting to fellow aspiring comedian Moss Perricone. “Well, I don’t care about getting in because I’m just going to do comedy by myself,” Sennott said. “This gives me a better push to go out in the city, where there are mics if you look for them.”

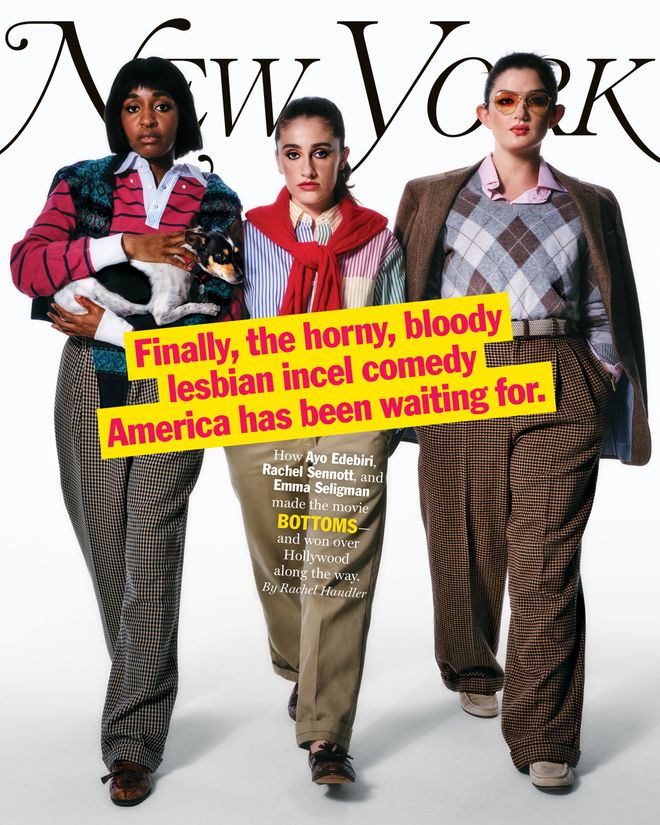

Cover Story

“I was like, Who the fuck is this?” says Edebiri, laughing.

“She’s blackout drunk, but she believes there’s another way,” Sennott says in a singsongy rasp.

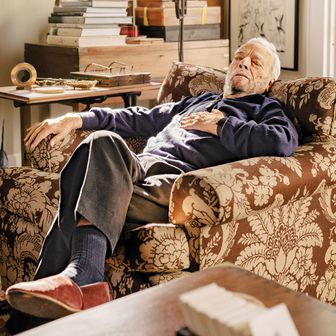

It’s a 90-degree June evening in Manhattan, and Edebiri and Sennott, along with the filmmaker Emma Seligman, their close friend and a fellow NYU grad, are sweatily crammed around a table in the back of Cafe Mogador, the first stop on a St. Marks Place bar-and-food crawl of their erstwhile haunts. Seligman, who studied film and TV production and uses she/they pronouns, first met Sennott when the latter ditched acting class to audition for Seligman’s senior-thesis short, Shiva Baby, a dark comedy about the central Jewish tenets of sex and death.

“She had me audition ten fucking times,” says Sennott, digging into the hummus. Okay, it was more like three or four times: an audition, a callback, a chemistry read, then a long lunch to go over all the beats of the character. “And I was like, ‘Am I going to be in this or what?’”

“Emma was like, ‘I’m Steven Soderbergh,’” says Edebiri.

“Emma was like, ‘You can have the role if you pay for half of lunch,’” Sennott says.

“But I did give it to you and changed your life, so … ,” Seligman replies lovingly.

The three have been filming shorts and sketches, writing scripts, and doing stand-up (with Seligman, not a comedian, watching from the audience supportively) together since their days at Tisch, from which Seligman and Edebiri, who are 28 and 27, graduated in 2017 and Sennott, 27, graduated in 2018. Five and six years after their respective matriculations, they’ve come together to make an extremely gay, impressively bloody, simultaneously fun-dumb and incisively smart studio comedy, Bottoms — directed by Seligman, co-written by Sennott and Seligman, and starring Edebiri and Sennott. In that time, all three have become more famous than the Hammerkatz pipeline ever promised. There’s Sennott on HBO’s The Idol, calmly explaining bukkake to her Gen-X co-workers and nervously driving the Weeknd around Los Angeles in a convertible as he goes down on Lily-Rose Depp in the back seat, and therapy-speaking her way into getting brutally murdered in the breakout 2022 Gen-Z-lampooning horror-comedy Bodies Bodies Bodies. Edebiri is so culturally omnipresent that her current five-movie, four-TV-show slate inspired a viral tweet deeming it the “Summer of Ayo Edebiri” — from guest appearances on hit shows like Abbott Elementary and Black Mirror and I Think You Should Leave, to getting nominated for an Outstanding Supporting Actress Emmy for her role on The Bear, one of the most popular series of the last few years. Seligman, meanwhile, turned Shiva Baby into a feature-length indie that blew up online and became a surprise pandemic hit, mostly via word of mouth, after its 2020 SXSW premiere was canceled. (Sennott stars in both versions.)

Bottoms, Seligman’s first big-studio project, follows Josie (Edebiri) and PJ (Sennott), two libidinous lesbian teen losers who start an after-school fight club under the auspices of sisterhood but actually do it just so they can fuck cheerleaders. They beat the shit out of one another while still having time to engage in a classic teen-movie war with the football team, convince their teachers they’re doing something important in the name of feminism, and try to get laid. PJ is the “Jonah Hill type,” as Seligman puts it, hard-core and proudly amoral in her quest to get “in the cooch” of her bulimic mean-girl crush, Brittany (Kaia Gerber); Josie is the Michael Cera, quieter and more of a romantic, in love with the quarterback’s co-dependent girlfriend, Isabel (Havana Rose Liu). Liu and Gerber lead a supporting cast of relative newcomers who are strikingly funny, committing wholly to the bit: Nicholas Galitzine and Miles Fowler as Liu’s douchey boyfriend and his scheming sidekick, ex-NFL player Marshawn Lynch as a clueless teacher on the brink of divorce, Ruby Cruz as PJ and Josie’s earnest third banana.

Bottoms was green-lit by MGM on the basis of Shiva Baby’s success, trading a budget of $200,000 for $11.3 million. It took six years, dozens of drafts, around 20 studio rejections, nine cavities, and a still-ongoing SAG and WGA strike to get to its August 25 theatrical release. It’s had the lesbian Letterboxd crowd, which treats every trailer and teaser release like Gay Christmas, hot and bothered for months. After attending its hit SXSW premiere, comedian Jaboukie Young-White tweeted, “There will be a full reset when this drops.”

Bottoms has all the adolescent horniness of Superbad, the unabashed lesbian energy of But I’m a Cheerleader, the winky visual Americana freshness of Bring It On, and a sharper satirical bite than Not Another Teen Movie. Though the movie is clearly made in the image of the early-aughts raunch comedies all three grew up on, it feels like the triumphant arrival of a new comedic collective, one that’s a lot more feminine, weirder, and, forgive us, hotter. And not unlike those of Judd Apatow or Christopher Guest, this universe is made up of people who create and write things with and for their friends: Sennott and Edebiri, of course, but also fellow comedians like Mitra Jouhari, who’s in Clone High and Big Mouth with Edebiri, and Molly Gordon, who co-starred in Shiva Baby as Sennott’s love interest and recently cast Edebiri in her own directorial debut, Theater Camp. Gordon also co-stars with Edebiri on the new season of The Bear (Jouhari pops up briefly too), which she got cast on after meeting showrunner Christopher Storer on the set of Ramy, whose creator, Ramy Youssef, directed an episode of The Bear and is hosting Edebiri while she’s in New York … You get the idea.

If you ask their NYU contemporaries, Sennott, Edebiri, and Seligman weren’t necessarily the people they might have guessed would catapult to Hollywood-blockbuster-level fame — nor did the three of them see things going that far this quickly. “I feel grateful to Emma forever,” Sennott says, “because she said to me, ‘You can be an actress, you can be the lead.’” All three did some form of that for one another over the course of their early friendships. After they shot the eight-minute short version of Shiva Baby in Sheepshead Bay, Sennott and Seligman went to lunch and shared their plans for the future. “Rachel was like, ‘Do you want to write something together?’” Seligman recalls. “I was like, Well, this girl is hilarious, so I’m going to pitch the one comedy idea I have.” She told Sennott, “I want to make a teen sex comedy but for queer girls.” Sennott loved the idea. “It was the first time I ever told someone my age that I had ideas, and the response I got was, ‘When do you want to do that?’” recalls Seligman. “She took out her agenda and was like, ‘We should meet once a week. Are you free Wednesdays?’”

As they remember it, Tisch was a preposterously competitive place filled with serious people trying to impress other people. But you couldn’t seem like you wanted success too much — that was gauche. Edebiri and Sennott weren’t worried about that. “I didn’t have parents that could fucking support me,” Edebiri says. In class, she found it hard to hide her displeasure when she felt that her classmates’ work wasn’t good or that they weren’t trying as hard as she was. After one lesson, one of her professors, the playwright Kristoffer Diaz, amused by Edebiri, held her back. “We’re going to work on your poker face,” he said.

Sennott was also a proud try-hard, the kind of 18-year-old who would break down her goals into three-month, six-month, three-year, and five-year increments, then actually complete them in their allotted time slots. The two quickly bonded over their unconcealed ambition. After that rooftop party, they filmed a mutual friend’s sketch, “Dean’s Hangout,” and Sennott pushed Edebiri to do stand-up with her. “At first I was like, ‘Leave me alone, dog,’” recalls Edebiri. Then one night, Sennott put her name on a lineup without her permission. Edebiri did ten minutes onstage and crushed it. “Rachel was like, ‘Told you, bitch,’” Edebiri says. They would schlep to the Creek and the Cave (a since-shuttered comedy club in Queens that flooded regularly), wait hours to go on for a few minutes, wolf down wet burritos, and, occasionally, get food poisoning.

Eventually, they found their way into a comedy scene flourishing off-campus — the weird women of alt-comedy, like Catherine Cohen, Patti Harrison, and Jouhari, all of whom were, to varying degrees, exploring gender performance and the innate horrors of womanhood onstage, often playing arch, heightened versions of themselves, narcissistic and ditzy and fame hungry and flawed. They invited the two to perform at It’s a Guy Thing, their monthly show in Brooklyn that combined stand-up, improv, and ironic PowerPoint presentations about “Guys of the Month.” “Cat basically invented me,” Sennott says of Cohen. “She was like, ‘Come in here. This is fun.’”

Seligman was in another world on campus, where everyone was making artsy music videos and trying to casually one-up one another while chain-smoking indoors at parties — a social scene she felt out of place in. She’d grown up mainlining Judd Apatow, the Twilight films, and cinephilic mainstays like the Coen brothers and wrote blogs for HuffPost Teen with headlines like “This Is Why The Hunger Games Is the Greatest YA Saga.” But she was not yet translating that populist-comedy–meets–film-nerd sensibility to her early schoolwork, which skewed grave. For her senior thesis, she’d originally outlined a wordless, Mad Max: Fury Road–style story about young girls protecting their land in a world where there are only women. Her professor found it vague and encouraged her to make something more plot-driven and personal.

So she started over and wrote what she knew, funneling into the script her Jewish upbringing and love of TV shows like Transparent as well as her feelings about her own complex situationships. She was sleeping with older men and “doing it for validation,” says Seligman, who realized she was queer and “liked more genders than just men” between her sophomore and junior years. The resulting short, Shiva Baby, was a flop-sweaty anxiety comedy about sex, power, and transactional sluttiness, following a Jewish college girl who runs into her sugar daddy and his goyish wife at a family shiva and spirals out, binging on bagels and lox while being accused of looking like “Gwyneth Paltrow on food stamps” and begging her mom to remind her who died.

A couple months after wrapping the short, Seligman and Sennott got to work on Bottoms (then referred to as Untitled Gay High School Movie). On its face, Bottoms diverged wildly from Shiva Baby’s indie realism, but for Seligman, the two shared a common goal: inserting queer characters into all of her beloved genres. They met up a few mornings each week, ducking in and out of coffee shops, holding “writer’s retreats” at Sennott’s dad’s uptown apartment, scrawling on whiteboards at the NYU production lab, and talking over Zoom when Sennott moved to L.A. to play Kyra Sedgwick’s daughter on the short-lived ABC sitcom Call Your Mother. Their dynamic was clear and complementary: Seligman grounded the characters and created a sense of plot and structure, while Sennott was “a literal joke factory,” says Maria Rusche, the director of photography on Bottoms, who shot some of Sennott’s early college shorts.

Seligman had first thought of Edebiri for the role of Josie their senior year. They hadn’t officially met yet, but she’d noticed Edebiri at a salon held at a filmmaker’s offspring’s apartment (they won’t say whose) over the Whole Foods on Houston. The vibe was “Tisch-y,” says Seligman: dimly lit, everyone sitting on the floor reading poetry, playing guitar, screening their short films. During a quiet moment, Edebiri inexplicably did an impression of Maggie Smith’s dowager countess on Downton Abbey. Seligman was the only one who laughed. “She was so bubbly and herself,” she says — “Desperate for a connection,” Edebiri cuts in — “so awkward and sweet and kind.” When they started working on Bottoms, Seligman asked Sennott, “Wait, you know Ayo? That would be the girl I would want for Josie.”

In 2018, Sennott and Seligman sat down to sell the idea to Edebiri, who, at the time of the script’s genesis, was juggling multiple side gigs including babysitting, handling the reservations line at ABC Kitchen, and working as a receptionist at UCB. It was difficult, at first, for Edebiri to trust that the movie would actually happen — they’d all just graduated from college, she had student loans to pay, and they were surrounded by flaky theater kids with overblown ambitions. “You sent me a draft I never read,” Edebiri admits to Seligman. (Later, she confirms the email is still sitting unread in her inbox.)

“Let’s unpack that. I’m not offended,” Seligman says, studying her. “I’m just curious.” Where Edebiri and Sennott are constantly riffing and joking, she is the most watchful of the trio with an energy that feels both quietly centered and a little dissociated, like maybe in her head she’s off somewhere reediting her upcoming movie.

Edebiri laughs. “It wouldn’t make sense if you were offended,” she replies.

Sennott jumps in. “I think it’s this thing where there were so many times I would try to work with people in school where we would be like, ‘We’re going to make a sketch every week. We’re going to do this — ’”

Edebiri interjects: “And then it doesn’t work out. I was fucking broke, working multiple jobs, and I’m just like, Okay, if we’re making a movie, I’m supposed to take what, three weeks off? And I don’t know what it’s going to be. But maybe something amazing will happen.”

For a time, they continued their individual hustles, balancing their art with classic (-ish) recent-Tisch-grad jobs. Seligman baby-sat on the side while working on the Shiva Baby feature, which took the premise of the short, raised the stakes, extended the run time by 70 minutes, and made it a lot gayer. Sennott got a job as an ATM mechanic, thanks to her dad’s owning a handful of them (something she works into a perfectly grotesque early sketch wherein she falls in love with one of the machines), and started hosting shows at higher-profile venues like Union Hall and Caveat. She increasingly gained a following online, posing for exaggeratedly thotty selfies on Instagram with self-deprecating captions and writing sardonic, hyperpersonal tweets that covered some of the same ground as her stand-up: the spectrum of disappointments inherent in dating straight men in New York, giving blowjobs to the sounds of Lana Del Rey, and the time she was addicted to poppers. In 2019, she got major attention for an 18-second video mocking L.A. (“If you don’t have an eating disorder? Get one, bitch!”), perhaps inadvertently creating the blueprint of what would come to be known as the Quintessential Rachel Sennott Character: whimsically delusional, bitchy, with an unself-aware banality. Edebiri, meanwhile, was doing stand-up and hosting her own shows; her humor was more heightened, punctuated by goofy physicality and sociological skewering. (“The same way that a group of fish is called a school,” she says during a bit about gentrification in Bed-Stuy, “when I see three white women who were conceived in an Anthropologie and born and raised in a Reformation, that’s called a Haim.”) Her career in Hollywood was starting to pick up too: In 2019, she broke into comedy writing, landing a gig on NBC’s Sunnyside, which led to staff writing jobs on shows including Netflix’s animated Big Mouth and Apple TV+’s Dickinson — on the latter two, she made such an impression that she was yanked from behind the curtain and given recurring onscreen roles.

In 2020, when networks were still taking chances on new voices, Edebiri and Sennott co-wrote and co-starred in a Comedy Central miniseries titled Ayo and Rachel Are Single, a too-brief three-episode inquiry into the lunacy of dating in New York. They play two women trying to convince themselves and each other that everything happening to them and around them is fine and normal, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. In the first episode, they’re on a double date and both of their dates desert them after the women behave like self-involved assholes. Before they arrive, Sennott, with that hallucinatory self-assuredness native to many of her characters, tells Edebiri, “I have no flaws, and neither do you. And that’s what feminism is.” Edebiri smiles. “That was beautiful. That’s Gloria Steinem, right?” she says. “I’m mashing a couple of quotes together,” replies Sennott. It’s a perfect distillation of their comedic chemistry, which reads like a surreal, fast-paced Ping-Pong match: Sennott serves up something demonstrably false with an unearned sense of sweeping confidence, and Edebiri, nonplussed and deadpan, calmly hits it back a little higher and slightly to the left. Then they both throw their racquets into the air and walk off the court to get a drink.

Ayo, Emma, and Rachel: A Friendship timeline

It may be a perfect moment to unleash a studio comedy about Machiavellian lesbian incels onto the world. Bottoms is a fascinating counterpoint to the Hillary-core, girlboss feminism of its immediate predecessor, Barbie, challenging the idea that women are unilaterally good, that they can measure or even prove that goodness by, say, winning a Pulitzer Prize or being an “ordinary mom,” or that this goodness means they deserve gender equality. Josie and PJ turn that sort of 2016 feministspeak on its head, exploit it for their own benefit, and incidentally expose it for the frail, condescending argument that it is.

The film takes place in a fake small town in a sort of inverted parallel universe where every categorically stupid thing entrenched in the foundation of America is made painfully, hilariously obvious: the homoeroticism of American football culture (the team mascot has a giant swinging dick, and the quarterback is effete), the travails of contemporary white feminism (“I thought the club was for sisterhood. But it was for your own selfish interests? This is the Second Wave all over again,” complains a Black fight-club member), the false promise of representational identity politics (“No one hates us for being gay — they hate us for being gay, untalented, and ugly,” is a repeated refrain between the protagonists). In one memorable scene, a teacher, played with mind-blowing comedic timing by Lynch, calls Amelia Earhart a “fake hero,” complaining that many men have flown planes without crashing.

Soon after Shiva Baby’s 2020 premiere, Alison Small at Elizabeth Banks’s and Max Handelman’s Brownstone Productions read the script for Bottoms and was impressed by its ballsiness. Edebiri officially signed on after that. At first, Small had trouble selling it to studios. “A lot of the feedback we got over the course of making the movie was, ‘I can’t believe girls are saying this,’” Small recalls. Then she met with Alana Mayo at Orion Pictures, a Black queer millennial who’d previously green-lit movies including Till and Women Talking and who understood the whole ludicrously horny thing. Under her leadership, the studio had minimal notes, none of which were about making the movie less graphic or gay.

They didn’t end up going too far in terms of graphic sexuality anyway, in part because Seligman wasn’t confident depicting it. “I don’t think I felt comfortable having tons of sex scenes between the characters because I’ve never really seen that in a theatrical movie, where there’s raunchy nude sex scenes among queer female characters,” she says. Still, she feels the movie is exactly as sexually filthy as it needs to be. To the homophobes of America, the movie went plenty far. Several of her desired locations in New Orleans, where the film was shot — including schools, football fields, and community centers — turned down her filming requests. Seligman later learned the Archdiocese of New Orleans had read Bottoms’ logline in a W article (“My first reaction was, The Archdiocese reads W mag?” she jokes) and has “a lot of sway over these places.” (They ended up filming the school scenes at an abandoned elementary school and Dillard University, a small local HBCU.) She was also shocked when they weren’t able to get any product placement, even from the most outwardly progressive corporations, because they were “too offended by the content.” She won’t name any names but tells me, “Just think of any liberal corporation that has a Pride float. They were like, ‘Not only will we not do something with you, but do not put anything of ours in there.’ It was really disheartening.”

Especially because they knew their target demo was out there, salivating (respectfully). “When we were pitching it, I was like, ‘There’s a whole audience of young queer girls being catered to in music with all these young queer AFAB or dyke musicians, like King Princess or MUNA or Girl in Red or Hayley Kiyoko.’ I was like, ‘There’s a rabid audience that has not been served that will come to the theater,’” says Seligman.

All three knew the audience. To various — and variously vague — degrees, they’re part of it. Seligman used to identify as bisexual, but six months before filming Bottoms, she stopped dating men. Neither Sennott nor Edebiri will pin themselves down, though they both talk around and hint at the fact that they’re not exactly straight. Edebiri brings it up first when we’re at Mogador: “I don’t know how many interviews you guys have done for this, but there’s this thing that’s been happening where people are like, ‘And give me your identity,’” she says to Sennott and Seligman, who nod vigorously. “It’s so boring to me,” she adds, getting increasingly animated. “You can already assume so much when you look at me. I’m like, ‘Why do you care?’”

Seligman laughs in recognition, imitating someone approaching her out of the blue: “So excited to talk to you. So, are you gay?”

“And tell me how many women you’ve slept with and why?” adds Edebiri.

“If you actually hang, you’ll hear the stories and then you’ll know,” says Sennott. “If you were there sophomore year, you’ll know.” (She doesn’t elaborate.)

When I follow up with them later to make sure I identify them correctly, Edebiri tells me she doesn’t want to outright label herself. “Part of my refusal to identify is because I think what happened to that young actor on Heartstopper is fucked,” she says, referring to the Netflix show’s lead, Kit Connor, whose fandom forced him out of the closet to prove he wasn’t appropriating gay culture by playing a bisexual teen. “And I’m glad he’s out and happy or whatever. But it’s one of those things where I’m like, ‘Bro, this is not how we do progress. We are being worse than whatever you think the other side is. If you think this is a way to liberate people, it’s not.’” Edebiri, who grew up in a Pentecostal community, also feels caught in a personally difficult spot. “I feel like this movie will appall my family,” she says. “A family member was like, ‘Did they give you more money?’ And I was like, ‘What are you talking about?’ And she was like, ‘Well, you’re playing a lesbian. Did they give you more money? Because isn’t that going to be harming your career?’”

She says she’s comfortable with me quoting her talking about things like having crushes on women and joking about the first CD she ever bought, composed of Emily Dickinson poems read by Sharon Stone, Meryl Streep, and Cynthia Nixon. “It’s just like, Okay, so there’s something going on here, you know,” she says, laughing. Sennott answers similarly: “Sexuality is honestly fluid. And it becomes this whole thing where people demand to know stuff about you. It’s a little invasive, honestly. Do I have to tell everyone every little thing I’ve experienced?”

Seligman feels strongly about the right for both to keep things murky. “I don’t think anyone should feel pressured to put a pin on their sexuality and name who they’re fucking if they don’t want to,” she says. “I do find it frustrating when people assume they’re straight and are like, ‘Here are these straight actors playing these queer roles.’ And I’m like, ‘You don’t know anything about anyone.’ Any public-facing person who doesn’t identify what their sexuality is, people assume it means straight. And that’s so often not the case.”

When they first started writing Bottoms, Seligman and Sennott felt the need to plainly identify each character’s sexuality and stressed about the credibility of their own sexual identities. “Should Josie and PJ be bisexual because we’re not lesbians?” wondered Seligman. “Or at least at the time I wasn’t. Do we need to make that clear? I was trying to be really PC, and as time went on, it felt like we were forcing identity politics into the movie where it had no business being there in terms of this world where everything is so heightened.” Instead, in a later scene, several characters have epiphanies about their sexualities: One character, for example, watches two other female characters make out and looks thoughtful. “Okay, yeah, I’m not gay,” she says to herself. “I just like gay porn!”

Seligman, Edebiri, and Sennott leave a comedy show the latter two were hosting and make their way to a LES Film Festival party, where the Shiva Baby short was screening, in May 2018.

Sennott, Seligman, and Edebiri debate whether it would be funny, stupid, transcendent, or all of the above to wander into the Boschian bowels of St. Marks to get spontaneous matching tattoos.

“My mom will love it when we get SLUT tattooed on our arms,” says Sennott, currently tattooless. “No, no,” says Seligman nervously. She already has several tattoos, including one that says MAKE GOOD ART, which she got right before heading to New York from her native Toronto at 18 to do just that and which she’s now too embarrassed by to explain further. Edebiri has four — all hidden — including one shared with another longtime NYU friend, Olivia Craighead, that references a random line spoken by Don Cheadle in Ocean’s Eleven. She drunkenly told Cheadle about it when they met recently at an awards show to her immediate regret. “I was like, ‘As a young Black actor, you’re such a prominent character actor and you mean so much to me. I have a tattoo of when you said ‘Barney Rubble — trouble’ in the Cockney accent,’” she says. “And he was like, ‘Okay …’ I don’t know what either of us were supposed to get out of the interaction.” She has at least three future tattoos planned with other friends (including Gerber, her Bottoms co-star) and “doesn’t want to get too full up.”

Sennott suggests a trip to Van Leeuwen down the street for ice cream instead. As we walk over, some kind of lower-Manhattan, Gen-Z–millennial–cusp comedy-celebrity alert system gets activated, and the next 30 minutes transform into an impromptu meet and greet. They’re stopped outside by a man who went to college with all three and now lives in L.A. (Edebiri and Sennott moved to L.A. in 2019 and 2020, respectively, and now live a five-minute walk from each other; Seligman gave it a brief shot but quickly came back to Bushwick.) They discuss the various storage units they still pay for in New York as the final holdout from becoming actual L.A. residents. Inside, the woman behind the ice-cream counter looks at Sennott with obvious delight as she orders a cup of vegan peanut-butter brownie honeycomb. “Oh my God! I love you on The Idol,” she says. Sennott looks briefly startled, then launches into a cheeky assessment of her performance on the series as Depp’s beleaguered assistant. “I am rocking that blazer,” she says. “Just wearing that blazer every day.”

The same woman turns her gaze to Edebiri. “You’re in …” she trails off, waiting for an assist, her mouth hesitantly forming a B — The Bear? Edebiri stares back at her, not unpleasantly but not helping to jog her memory, either.

Outside, Sennott sighs. “I feel like everyone hated us,” she says. She’s perpetually aware of and concerned about the feelings of everyone in her blast radius. Edebiri, while not exactly comfortable with being publicly perceived, doesn’t seem to adjust to her audience. She raises an amused eyebrow. “No, they literally loved us,” she says. She replays the ice-cream-shop woman’s reaction: “It’s always like, ‘Have you been in anything I’ve seen?’ I’m like, ‘I don’t know what you fucking watch!’” She also hates being set up by strangers to seem too self-congratulatory. “Like, ‘Oh, you might know me from Comedy Central videos.’ And they’re like, ‘No, you actually just look like my cousin.’” Recently, someone told her they recognized her by her hands, which are often filmed lovingly preparing fresh pasta and Italian beef on The Bear.

We head toward our next destination, the bar Sly Fox, one of the trio’s college mainstays, which Sennott describes as “the worst” and “really great.” Before we go inside, we’re interrupted again, this time on the sidewalk by three giggling teenage white girls. After the girls walk away, Sennott blames herself. “This is a problem. I make eye contact with everyone on the street,” she says. “They’re like, ‘We just wanted to say hi.’ I’m like, ‘Come on, let’s walk. Where’s your family from?’” Edebiri laughs and says, “You have to figure out how to close up your eyes.” Sennott ponders this point. “I think I extend it for so long because I don’t want anyone to ever be like, ‘She was a bitch.’”

Two weeks before Bottom’s release, Sennott and Edebiri deleted their accounts on the platform formerly known as Twitter, which they told me they had planned on doing back in June. “I have moved away a bit from ‘I’ll tell you everything every second,’” says Sennott. “You want to be able to change as an artist, keep your privacy, but also keep the special thing that drew people to you in the first place.” Over the past two years, Sennott’s Instagram has evolved from a tongue-in-cheek take on the platform — posing poutily in a low-cut top over a plate of sushi, captioned “Pic of me enjoying a meal” — to a more straightforward look at the glamorous facts of her life as she ascends to stardom: standing on a red carpet in a leather tube dress at Variety’s Young Hollywood Party, holding a Celine bag with the caption “U know I love my celine #celinepartner,” boating on vacation with social-media comic turned actor Jordan Firstman and Theater Camp star Owen Thiele. Edebiri’s, previously populated with goofy photo dumps and promotion for her solo stand-up, is now partly a showcase for her fashion-girlie glow-up: She’s wearing white Loewe dresses studded with bright-red balls to the Time 100 red carpet, posing on a luggage cart in a Thom Browne tux with a dramatic skirt, gracing the cover of Variety and in Forbes’s “30 Under 30,” tagging her glam team in photos from the Indie Spirit Awards.

Edebiri feels some angst about the whole thing too. “My anxiety is when you put up the boundary, now all you hang out with are other celebrities at Erewhon,” she says. “And you don’t have an inner life anymore because you’re so afraid of protecting your own privacy.”

At first, nobody believed Bottoms would actually feature teenage girls punching each other in the face. When the movie was sold to Orion, one news outlet put quotes around the term “fight club” when describing the film’s plot. “It felt like a piece of information that was hard to communicate,” says Seligman. That misunderstanding trickled down to the male crew members on set. Seligman remembers an assistant director remarking, “So this is Marvel?” when he realized what he’d signed up for. “Clearly he thought, I was going to do some teen comedy, and now I have to plan stunt sequences.” Seligman and Rusche choreographed the stunts themselves and hired a professional stuntwoman, Deven McNair, who trained the cast for two weeks in New Orleans before shooting began, teaching them to pretend to take it in the face and the gut, the difference between an uppercut and a right hook, how to slap, how to fall. “It was this weird, fucked-up summer camp,” says Gerber, who put herself on tape for what ended up being her first speaking role in a feature. “It felt like we were filming a war epic.”

Bottoms shot in 27 days over the spring of 2022. Seligman struggled with the whiplash of scaling up her Shiva Baby budget by $11.1 million. On her first feature, she’d “begged for pennies till postproduction” with the biggest splurge being adding one more day to shoot B-roll of extras eating bagels. On Bottoms, she could tell her production designer, “I want a painting where it’s like the Sistine Chapel but the quarterback touching a football,” and he’d paint it in the cafeteria. She also struggled to figure out how to be taken seriously by the crew, many of whom were older men.

“I’d never worked with that many men — that’s not a bad thing,” she says, carefully. The three start talking over one another.

“No, but it’s — ”

“They weren’t all — ”

“Some of them were very lovely, but it was just like — ”

“Yeah, and all of the women were — ”

Edebiri takes a breath. “Asserting authority to these 40-, 50–year-old male crew members, who, again, many were truly lovely and wonderful, but there’s certain things about power and how power appears that they gave you a hard time for,” she says. “Honestly, it’s also you, your nature and your style, you don’t want to yell at people. Some of those men, or people in general, did not respond to it.” Sennott and Seligman nod — Seligman tells her she “appreciates that” — and Edebiri finally just goes for it. “It was fuckin’ wack,” she says, referring to moments when the crew messed around while Seligman was speaking. “Me and Rachel would be like, ‘We’re not laughing at your jokes, and we’re ignoring you, because Emma’s talking.’”

Throughout filming, Sennott and Edebiri grew even closer, “sharing a brain,” as they put it, plus a honey-wagon trailer. They pushed each other comedically, supporting their out-there improvisations, like an early, spiraling monologue from Edebiri about a sexless, lonely future wherein she’s forced to marry a gay friend who becomes a closeted pastor and they raise a resentful child. That’s not to say filming was conflict free. Seligman and Sennott had developed a directorial shorthand after both Shiva Babys, a chatty, detail-driven way of working, tracking the emotions on every page ahead of time. This chafed against Edebiri’s more experimental sensibility. At Sly Fox, they go back and forth remembering how Seligman had to adjust her preferred technique for Edebiri, who wanted to try things for herself first in a scene before being explicitly directed.

“You were like, ‘Stop talking,’” says Seligman, laughing.

“Because I’m like, ‘Do you trust me? And if I’m wrong, we do another take,’” says Edebiri.

“You challenged me to back off,” says Seligman. “To let you and the comedy breathe. It was a great challenge to not micromanage.”

“We all wanted the best for the movie,” Sennott says, “so there were moments where it was difficult as friends. You can’t every day be like, ‘Queen, I love you.’”

Our last stop of the night is a private room at Sing Sing Karaoke. After this, they’ll go their separate ways for a while: Edebiri is flying to Paris Fashion Week, and once the strike wraps, she’s filming an undisclosed role in Marvel’s Thunderbolts. Sennott is headed back to L.A. and, in September, will be in a film, the Italian period piece Finalmente L’Alba, premiering in competition at the Venice Film Festival. Seligman will go back to Bushwick, where she’s already working on other scripts. She doesn’t see herself solely as a comedic filmmaker — “I want to make something of every genre” — citing people like Denis Villenueve and Greta Gerwig as inspirations. She’s not opposed to going full franchise mode, “making a cool, fucking artsy multimillion-dollar movie on a Marvel level.”

Will Bottoms allow them to keep doing their specific brand of gonzo comedy, or will they inevitably level up and lose some of that NYU-bred magic? Will they keep making weird shit together, or will they each get sucked into the rapidly whirring fan of the IP machine? Does Bottoms mark the beginning of something or the end of it? Edebiri and Sennott express a desire to keep at least one foot firmly planted in the Seligman Cinematic Universe, wherever it goes, but they’re also shooting their Hollywood shots — Edebiri says she wants an acting career like Emma Stone’s, while continuing to write and produce, and Sennott is currently writing a movie she’d like to direct.

At Sing Sing, Edebiri admits that she can, on top of everything else, sing. She instantly puts on Kate Bush’s “Wuthering Heights” and does a staggeringly good rendition, hitting the falsetto effortlessly from a casual seated position. “It’s pure terrorism to do this song,” she says by way of explanation. “I only do terrorism joints.”

“That’s Mommy,” says Sennott.

Edebiri searches the catalogue for her next song: “They don’t have Creed? What the hell!”

Sennott, who lost her voice at a Bottoms screening in Provincetown over the weekend, talk-sings Taylor Swift’s “Paris.” “I wanna brainwash you / Into loving me forever,” she says in an extra-gravelly alto. Seligman, who says she’s shy and doesn’t love karaoke, wonders aloud about doing a song from Wicked or Little Shop of Horrors.

She polls the room: “I want to do a Rent song we all know. Do we all know ‘Take Me or Leave Me’?”

Edebiri raises her eyebrows. “Be serious now. In this room? Be for real.”

All three belt the song from start to finish with perfect recall. “Women?!” they scream into their mics. “What is it about them? Can’t live! With them or without them.” It’s about a pair of batshit lesbians engaged in a psychosexual drama of their own making, all in the name of getting laid. They occasionally want to murder each other but have once-in-a-generation chemistry.

*An earlier version of this piece incorrectly referred to male crew members as Teamsters.