Vince McMahon did much to hurt Bret “The Hitman” Hart over the thirteen years in which the legendary wrestler worked for him. As owner of the World Wrestling Federation (WWF, now known as WWE), McMahon first encountered Bret in 1984 after McMahon bought Stampede Wrestling, the West Canadian promotion owned by Bret’s father. McMahon never paid the Hart family for the purchase; they didn’t sue because Bret would’ve lost his new job.

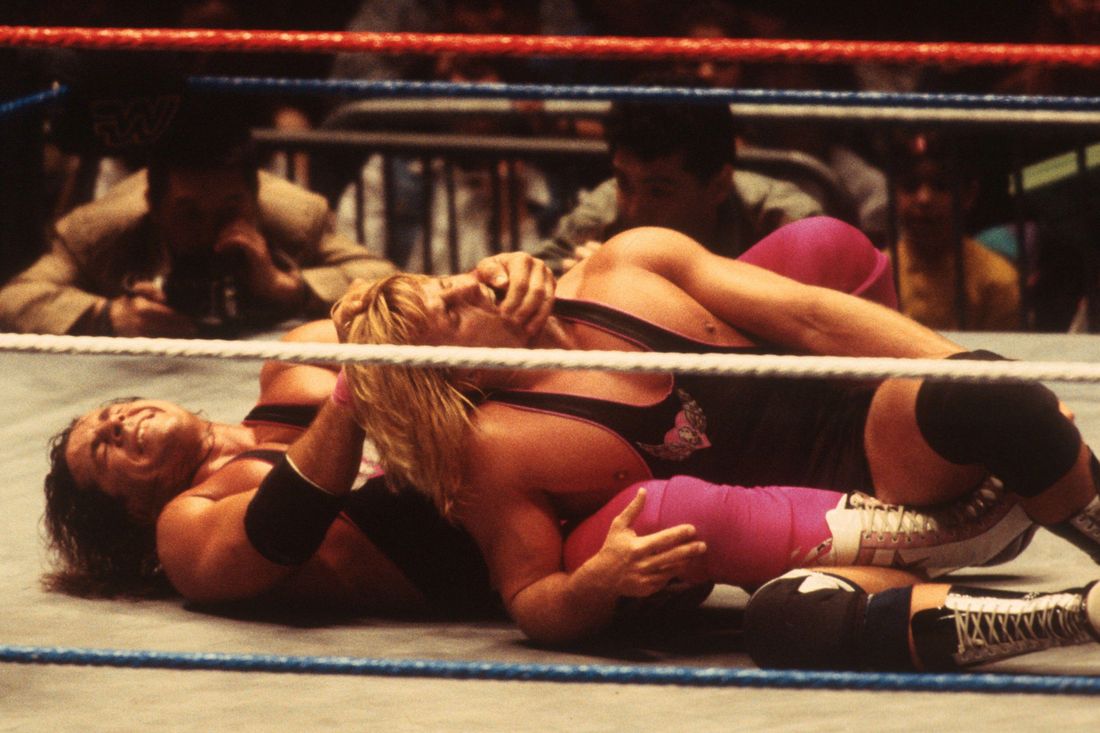

McMahon worked Bret hard in the WWF, dangling opportunities and then snatching them away with a cackle. In 1997, McMahon subjected Bret to what is known in the wrestling profession as a “screwjob”: without telling Bret, McMahon flipped the script in a high-profile match and told the referee to declare Bret the loser, taking away his championship in humiliating fashion. Bret left for Ted Turner’s World Championship Wrestling (WCW) immediately afterward.

Less than two years later, on May 23, 1999, Bret’s beloved younger brother Owen, who was working for the WWF, fell more than seventy feet during a sloppily coordinated zipline stunt at a live WWF show. Owen hit the ring in front of thousands and died soon afterward. McMahon decided to keep the show going, and it ran to its completion. The following excerpt from my new book, Ringmaster: Vince McMahon and the Unmaking of America, picks up in 1999, shortly after Bret learned of his brother’s tragic death.

Excerpt From 'Ringmaster'

In the immediate aftermath of Owen’s death in 1999, Vince kept leaving voice mails for Bret, asking to talk.

Bret wasn’t sure he wanted to talk to Vince. The two men hadn’t spoken since the Montreal Screwjob, and Owen’s death was still being investigated by the Missouri police. “I didn’t want to be too friendly because I wasn’t sure at that point that it was an accident,” Bret tells me. “I didn’t know if it was about revenge about what happened with me and Vince.”

So Bret ignored Vince’s calls for days. But shortly after Owen’s body arrived home in Canada, Bret sent Vince a message through a mutual contact: he would meet with Vince in person on a park bench in Calgary, overlooking the Bow River.

It was an unseasonably cold, overcast day. “Vince wore a long heavy coat,” Bret wrote when he told the story in his memoir. “He slapped me hard on the shoulders, hugged me, and told me how sorry he was.”

He remembered Vince saying, “This is the worst thing to ever happen in the business, to the nicest guy who was ever in the business.”

Bret told Vince that he hadn’t liked Vince’s decision to go on with the show after Owen died. Vince claimed that he and everyone else had been in shock, and hadn’t known what else to do. Besides, the fans might have rioted if he’d shut the show down.

Bret wasn’t buying it.

“I said that if Shane [McMahon, Vince’s son] had been dropped from the ceiling, Vince would have stopped it fast,” Bret recalled. It never would have happened if he’d been there, he told Vince. He would have protected his brother.

Then, they had to talk about the reason Bret hadn’t been there.

“There isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t regret what I did to you,” Vince told Bret. “You need to come back and finish your career with me. I could put the belt back on you.”

Vince paused, awaiting a response.

He got none.

“I could have a story line for you by tomorrow morning,” Vince offered.

Bret said he couldn’t imagine doing that.

Vince asked if there was anything he could do for Bret.

“When I still worked for him, we talked about doing a ‘Best of Bret Hart’ video collection, but that was more than unlikely after Montreal,” Bret recalled. “I didn’t have much of a history if Vince locked up everything I did in a warehouse somewhere.”

So Bret said, “Well, it would mean a lot to me if I could have access to my video history and photos whenever I need them—”

Vince cut Bret off: “Anything you want.”

“I don’t want to lose my legacy,” Bret told his old boss. “I don’t want to be forgotten.”

“You don’t even need to ask,” Vince said. “Anything you want.”

“I found myself thanking him,” Bret wrote, “and telling him how much this simple gesture meant to me, especially under the circumstances. If the police cleared Vince, then maybe I could forgive him.”

They ended up spending two hours on the park bench together. They exchanged stories about Owen and even managed to laugh a little. They shook hands and headed back to their cars.

But a few months later, Bret saw Vince being interviewed on TSN’s Off the Record, talking about their park bench meeting.

Vince told the interviewer that he’d met with Bret “only out of respect for Owen,” but that Bret had barely mentioned his brother—“all he wanted to talk about was himself.” He painted Bret as ghoulishly self-centered and intent only on rehashing their old grievances.

“It was like looking into the eyes of a skeleton,” Vince said of Bret. “It seemed like he wasn’t human.”

“That’s pretty cold-blooded,” Bret remembers thinking. “Talking about me looking like a skeleton three days, five days after my brother died.” By that time, members of the Hart family had filed a lawsuit against the WWF. It settled for $18 million in 2000; the WWF admitted to no wrongdoing.

Bret and Vince didn’t speak again for years. Much of the footage of Bret’s awe-inspiring work at the WWF would remain locked in the company vault. Even his later stint with WCW was beyond Bret’s grasp: Vince had acquired the WCW archive when he purchased the promotion in 2001. Bret had sustained a massive in-ring injury in 2000 that had effectively ended his career.

Now, unable to wrestle, it was the story that mattered most to Bret: his story. And Vince had a monopoly on that story.

Every match Bret ever worked, every bump he took, every time the crowd roared for him in the WWF: no one would ever see it without Vince’s say-so.

“I didn’t do all that work and have all those matches to just be forgotten,” he tells me. “It was so important to me to not be erased.”

To Bret, it was as if Vince was holding his past hostage. As the years went by, the company occasionally approached Bret to ask him to appear in one event or another—hinting that if he played along, they might find a way to release the footage of his work. Every time, Bret turned them down. Why should he bargain for access to something Vince had already promised to give him, back on that riverbank in 1999? At one point, a spokesperson told him Vince had no memory of the conversation.

Meanwhile, all anyone seemed to remember about Bret was the way his WWF career ended.

“Everywhere I went, it was always about the Screwjob. Every question, everything I did,” he tells me. “‘So what about Vince McMahon? What about the Screwjob? Did it really happen? Did you punch Vince McMahon? … Was it a work? Was it all pretend or was it a story line?’ ”

He’d always answer as honestly as he could, feeling himself tense up.

He hated having to go over it, again and again, explaining what he did and defending his actions.

The worst part of it was that he had to admit Vince had played everything brilliantly. “When people would ask me all the time about the Screw-job, it was kind of obvious that Vince had come out much better than I did on it,” he says.

The Screwjob had perfectly primed the audience for Mr. McMahon to become “the top heel in the industry,” Bret says. “You couldn’t have written it better. Like, you couldn’t have given them a better concept or idea. It was new. It was fresh, and it was masterfully done.”

So there Vince was, still riding high on the gimmick the Screwjob had launched. And here was Bret, his career over, his legacy obscured.

It was hard to swallow. But it was also hard to keep hating Vince.

When Bret tells me about his former boss, even as he lays out the many, many times Vince was cold or dismissive or manipulative or cruel, he keeps repeating that they could have gone further together. Bret thinks he could have ended his career as a booker, working with Vince to plot out incredible story lines. “I could have been his right-hand man,” he says. He repeats it several times.

In 2002, Bret had a serious stroke that paralyzed half of his body. He was lying in his hospital bed, unsure of the extent to which he’d ever recover, when the phone rang.

“And it’s Vince,” he says, “calling me, out of the blue.” The call caught him off guard. It was shocking to hear that voice, after three years.

“You’re going to beat this thing,” Vince told Bret on the phone. “You’re one of the toughest, strongest guys I ever knew. You got the mind frame and you’re going to get through this.”

The pep talk meant a tremendous amount to the wrestler. “I ended up kind of softening a lot of my hate and anger toward him and really kind of appreciated what was once a very strong relationship,” Bret says. “I kind of forgave a lot. I just felt a bit of a thread of what we had before the Screwjob happened.”

Slowly, Bret recovered from his stroke. And in 2005, two years after the death of Stu Hart, Vince finally followed through and released a DVD called The Best There Is, The Best There Was, and The Best There Ever Will Be, which featured some of Bret’s finest moments, along with a documentary. When it came out, WWE inducted Bret into the Hall of Fame, but Bret refused to participate in that year’s WrestleMania. He still felt he should never appear in one of Vince’s shows ever again.

However, in 2007, there came a night when Bret was all alone in his house in Hawai’i. He was going through a divorce, no work coming his way—his body had never come all the way back from the stroke, and he figured his time in wrestling was over for good.

WrestleMania was on. He decided to give it a watch. On the TV, Donald Trump—a man with no training or physical skill—was attacking Vince to the cheers of the crowd.

Hell, Bret thought. I could do that.

Bret called Kevin Dunn at WWE and said he might be willing to take Vince up on his standing offer to come back. Dunn, astonished, passed the word along. Vince was overjoyed and welcomed Bret back to the fold. In 2010, the Hitman made his world-stunning return to WWE programming as a character, doing low-impact pseudo-matches, taking bumps, and, most importantly, cutting promos about how he longed for vengeance against Mr. McMahon.

There was blowback. Bret says Martha, Owen’s widow, was furious at him for selling out and going back to WWE after what had happened.

“I was like, ‘You’re still so bitter and angry,’ ” Bret recalls. “That’s why I did what I did: it was so I wouldn’t end up like that, [where] everything is about what ‘they’ did and how I’m going to get ‘them’ someday… . “I just don’t think Martha understands how my family was wrestling,” he continues. “Everyone was so involved with wrestling. You couldn’t just cut it out of your life. My brother Owen died, so I’ve got to forget every single thing I ever did in wrestling? I didn’t want that.”

Going back, he says, wasn’t just about the money, or about letting go of his anger, or even about getting back in the ring. It was also about getting back into the story. “That was the biggest reason that I went back,” he tells me. “I wanted to rewrite my ending.”

And he did. “I don’t get asked a lot of questions about the Screwjob anymore,” Bret says. “My career hasn’t been based solely on that moment. And I’m maybe the most popular today that I’ve ever been in my career. I think I’m recognized by a lot of the wrestlers in the industry and a lot of the fans as maybe the greatest wrestler of all time, or in the short list of the top ten or top five … I’m always really glad for that. I could be still sitting in my house being miserable.”

A few years later, Bret was diagnosed with prostate cancer. On January 31, 2016, he was preparing to publicly announce his diagnosis.

“I was writing a statement to announce to the papers the next day that I was going in for prostate surgery,” Bret says. “I had it written.”

“And then,” he says, “I just called Vince up.” He continues: “I remember thinking about it: Why am I calling Vince McMahon, of all people? But it was … it was just …”

The tired grappler trails off. He thinks for a second.

“I knew that Vince … that he should know,” he says. “He’s gonna talk about it; he would appreciate me letting him know I had cancer and that I was going in for surgery.”

All surgery carries fatal risk. Bret had cheated death countless times, but, for all anyone knew, it could have been the Hitman’s last night on earth.

He dialed the boss’s number.

It went to voice mail. “And I said, ‘I just want you to know that I’m going in for surgery in the morning and I’ve been diagnosed with prostate cancer,’ ” Bret says. “And I was obviously kinda scared, and worried about what was gonna happen.

“Vince called me literally three minutes later and gave me a very strong pep talk and told me I was gonna do fine. He even did a post on the WWE internet or whatever next day,” Bret says.

“So I was glad I did it. I was glad I let him know that, for some reason, he was that father figure to me. That, maybe, he’d appreciate me letting him know what I’m dealing with.”

Bret pauses. We’ve been talking about Vince McMahon for many hours. He only has one thing left to say about the man.

“I don’t know how to explain my relationship with Vince,” Bret says.

“But I do know that, if I’d never crossed paths with him, I wouldn’t be the same man I am today.”