On January 23, 2024, Past Lives was nominated for two Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Original Screenplay for Celine Song. Be sure to also read our review.

It was the way people were looking at us.” In a bright corner of Café Mogador in the East Village, the filmmaker Celine Song is remembering the rendezvous at a nearby bar five years ago that inspired her debut film, Past Lives. On paper, the movie is a love triangle formed by Nora (Greta Lee), a Korean Canadian playwright in New York; her childhood sweetheart, Hae Sung (Teo Yoo), who resurfaces in adulthood; and Nora’s husband, Arthur (John Magaro), a Jewish American writer. Nora and Hae Sung knew each other as kids in Seoul, where Nora went by Na Young, before she emigrated westward with her family. Now an engineer, Hae Sung crosses the world to see her, and they embark on long walks that are rich with tender, curious glances and slow revelations. But Nora is married. In the opening scene, she sits between the two men in the Hopper-esque amber light of a bar. She is turned gently toward Hae Sung, engaging him in conversation in Korean as she swishes her drink, while Arthur, to her left, gives off a hangdog air.

In real life, Song found herself at Please Don’t Tell, a Manhattan speakeasy. The two men she sat between were an old sweetheart, a Korean engineer in business casual whose name she prefers not to share, and her white husband, the writer Justin Kuritzkes, wearing some “shitty shirt.” She felt the eyes of patrons on them and imagined their thoughts. Which one is the husband? Is he jealous? She felt any quick answer to the deeper implicit question — Who are they to one another? — would lack the intricacy of the truth. “You can feel the desire to know,” she says. “And if I’m gonna tell you, I’m gonna tell you for real.”

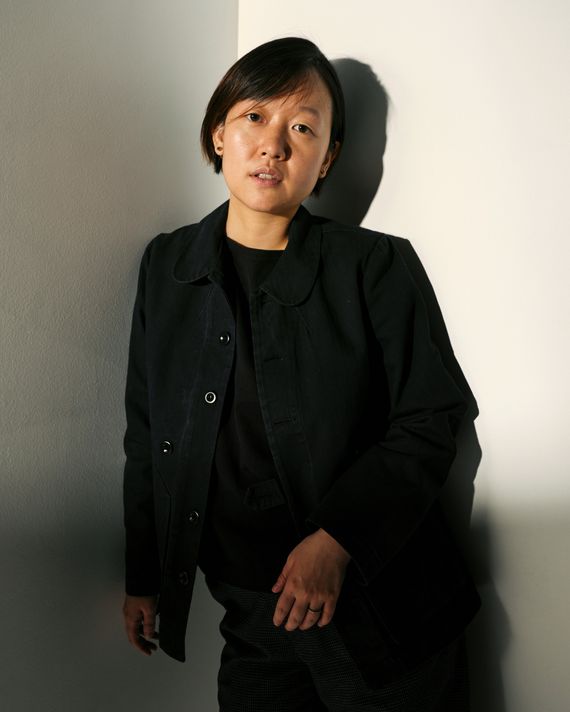

The result, Past Lives, written and directed by Song, premiered at the Sundance Festival and has been called the best debut feature in years — a bittersweet, jewel-like love story drawing comparisons to Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise trilogy. Song wrote it in 2018 after a career as an ascendant playwright known for formally unorthodox, confrontational plays about race, violence, and power. At 34, she has an “unburdened” conviction in her opinions, as her friend and Past Lives’ co-producer David Hinojosa put it, whether over something as small as what to eat or as large as what to write. Her efficient bob haircut frames an open, sensitive face. Past Lives represents the most public — and autofictional — flowering of her artistic fixations on the contradictions of a life, particularly her own. Who we are can determine who we love, and vice versa. Nora’s voyage as an immigrant and artist may seem to demand that she lose her ties to a motherland and to custom. Hae Sung, a middle-class Korean, arrives as an almost fantastical figure: ordinary yet magnetically soulful, a man through whom Nora could perhaps close the gap of displacement. Arthur, a native on the path through the artist’s life that she seems to choose with her every breath, may represent a future, but his presence can also seem to erase her past. It’s “an adult love story” about people who are trying to be mature, Song says. “I wanted the audience to feel there is a very real argument for why she should stay, the way there is a very real argument for Hae Sung. I don’t want the arguments to be lopsided. I want them to be even.”

Celine was 12 when she made the trip from Seoul to Canada. Her mother, an illustrator, was granted an artist visa for the family on the strength of a portfolio built from hundreds of children’s books. Celine’s father, Song Neung-han, is a quiet legend in Korean cinema, a writer-director who introduced key performers into the fold, such as Parasite’s Song Kang-ho — one of his earliest roles was in Number 3, a gangster comedy by Celine’s father. In one part of the world, “I’m a nepo baby,” she jokes. When she returned to Korea to shoot parts of Past Lives, the crew members told her they were excited to see what the daughter of Song Neung-han could do.

Her parents ran a crafts and accessories shop in Markham, Ontario, leaving behind their former professions. Celine was an energetic student. Her public high school had a Classics Club for which she wrote plays. By the time she entered Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, she had decided to study psychology and become a therapist. In college, she threw herself into activities, “trying to find out what my heart was really in.” She was on the editorial staff of half a dozen magazines, some to do with culture, some mental health. Then she saw a production of Bertolt Brecht’s Drums in the Night at her university. She became enamored with the playwright’s impulse toward provocation, how he used fourth-wall-breaking, immersive techniques to “implicate the audience” and force engagement with the biggest questions of existence. “What if you could do something that is harmful to another person, or evil, so that you can feed your child? Can you blame the mother for that? The child? Or the society that makes that a necessity for her to even provide for the child?” she poses. Song applied to theater schools and got into Columbia, where she studied under Chuck Mee and Anne Bogart, playwrights who had come up during the experimental heyday of the 1980s — “where you could make a living as a playwright and also do really form-breaking stuff,” Song says. When she arrived in New York in the 2010s, that scene was dying. Spaces that used to show experimental work were closing down every year or becoming corporatized. She describes live theater as a “subscriber based” medium: “You don’t want to be confrontational when you have a subscriber base that is old and white.”

In 2012, Song won a fellowship from the Edward F. Albee Foundation, which is housed in a converted white barn in Montauk where the playwright hosted emerging writers; the experience would change her life. “I met Edward there. I met my white husband there too,” she wrote in an essay marking Albee’s death in 2016. Kuritzkes was 22 (“A literal baby, literally just started to be able to drink legally”); Song was 24. Right away, “it’s so cringey, but we showed each other each other’s plays,” she recalls. “We’re either going to kill each other or we’re going to get married. That was the feeling we had.” She says Kuritzkes, a novelist and playwright, is “a very different writer” from herself, a polymathic figure with a surreally funny, pop-oriented bent. His first novel, Famous People, takes the form of a memoir by a pop star. His 2017 play Asshole imagines a doctor obsessed with the smell of his own asshole. But she saw a thread between them. “There are a lot of people who are great at writing, but it is harder to be somebody who has an ideology to their work,” she says. “I knew we were aligned in what we wanted to pursue.”

In her work, Song hoped to force engagement with existential questions that felt urgent to her. An early play, Family, explores the concept of inherited violence through three half-siblings conversing at the funeral of their father. That play involves incest. Another, The Feast, deals with the nature of desire and diminishing natural resources and involves cannibalism. In 2014, she wrote Beep and Boop Fight Crime, a play about police brutality inspired by the city’s stop-and-frisk program; the officers in it wear KKK hoodies and shoot civilians. Her plays landed in boutique studios and theaters, often for meager pay. One show netted her as little as $500 for its entire run. She worked at a matchmaking agency for one six-month stretch. Her clientele were young professional women in New York. Song half-jokes that she was so hooked the experience almost derailed her writing career. She was given psychological insights on a platter — candid confessions of racism, for instance. “People tell amazing things to a matchmaker,” she says. “I think you have more access than therapists because they know they’re not there to be judged.”

She and Kuritzkes married in 2016. By then, she had arrived at a conclusion: She had to leave the theater. There were the financial constraints, and her writing had begun to strain against the racial hierarchies built into the theater world and her own engagement with them. A new play she staged, 2016’s Tom & Eliza, was a sendup of the “white plays” she had felt conscripted into caring about, even while she revered the tradition they represent. It features a classic construct of the genre: two people in a couple work out what went wrong. In her version, Tom hoards books, Eliza burns them. She saw the characters, in part, as manifestations of her conflicted sensibilities toward the written word and the dramatic canon: both overprotective and destructive. The play was meant to be her last, but she was compulsively working on new pages as it went up. She finished with 2019’s split-brain, metatextual Endlings. It follows a group of haenyeo, the elderly Korean women who dive into the ocean daily to fish, but the big reveal is a character based on Song herself. She’s represented in scenes set in Manhattan, as a young Korean Canadian playwright alongside her playwright husband, whom she runs ideas through and who wears a placard in the Brechtian mode of representational props, identifying him as WHITE HUSBAND. Song explains to me her belief that because of the demographic makeup of theatergoers, most would experience the play’s haenyeo with a ticker tape running through their heads: ASIAN, ASIAN, ASIAN. Why not ID him, too? “I decided to write this play because I was trapped,” her character says in a monologue. “I first told some white people about haenyeo and how amazing they are. And then they were like, ‘Oh my God, that’s amazing; you have to write a play about them.’” She wrote it because she had been “bribed by white people’s attention,” the playwright character says.

Endlings became the highest-profile production of her career, with a premiere at the American Repertory Theater. COVID cut its New York run short, but Song had already started her transition, having joined the Amazon series Wheel of Time as a staff writer. She had also begun the screenplay that would become Past Lives. In 2020, the superproducer Scott Rudin picked it up and brought it to A24. Then, accusations of decades-long workplace abuse led to the severing of his deal with the company. Hinojosa and two other A24 stalwarts, Christine Vachon and Pamela Koffler, came onboard. Song says Rudin ultimately wasn’t involved with the production.

Song’s script is built on the Korean concept of inyun, or “destined connection.” The term gives shape to the largest and smallest aspects of Korean life the way karma might for Hindus. In its logic, interactions indicate relationships in past lives. There’s bad inyun, Song tells me: “We keep facing off with each other, and we don’t like that.” And there’s good: “That feeling of, Oh, how amazing we all ended up here,” when a meeting feels wonderfully ordained. You may love someone now because you hated them in an earlier life, or the opposite. And lives run thousands deep. “If two people get married, they say it’s because there have been 8,000 layers of inyun over 8,000 lifetimes,” Nora explains to Arthur. Hae Sung later asks her, “Who do you think we were to each other? Maybe an impossible affair?” As they trade hypotheses, Song’s elegantly spare dialogue reveals the subtle possibilities contained in the concept. “Maybe we were just sitting next to each other on the same train. Maybe we were just a bird and the branch it sat on one morning.”

In real life, as in the film, Song remet her childhood sweetheart over Skype before she met Kuritzkes. “We tried, and of course it was impossible,” she recalls. They lost touch, she got married, and two years later, he decided to visit. She was interested to see him, but whatever she felt was platonic now. Their inyun wasn’t strong — maybe only 7,000 layers, she jokes. Today, he has a girlfriend, she tells me. He knows about the film, and he’s “proud and excited” for her. The characters bear a resemblance to their real-life counterparts, Song says, but are their own people with their own relationships. Unlike in a tidy rom-com, the tension between them can’t be easily erased. Longing suffuses Nora and Hae Sung’s smallest movements, as if the film were a stylized exploration of that state, an old-fashioned, chaste yet erotic dance. “In another story,” Song says, “they would try to resolve it by sleeping together.” Here, they probe through speech. They smile. They are together and say nothing at all. Song told Greta Lee, who plays Nora, to think of herself as a host. She must care for the men to make sure they are okay, as a host does for a guest.

Arthur, Nora’s husband, can seem preternaturally understanding of Hae Sung’s arrival. Magaro points to Song’s own relationship as his template for the film’s liberated vision of love. Kuritzkes is “an understanding, caring, smart, creative partner,” he said. “There’s a lot of modern men like that. Without a supportive character like Arthur, you wouldn’t be able to facilitate Nora’s understanding of her past and identity.” Song tells me Kuritzkes is the first reader of her writing. And while they have no stated agreement as to how either of them might bring the other into their work, they are in constant communication about it. When I ask whether there were any discussions over Endlings’ WHITE HUSBAND placard, she seems almost confused. “He would have been the first person to point out that it’s strange if I didn’t say WHITE,” she explains.

Song speaks of the strength of her and Kuritzkes’s inyun, but she also sees destiny as a featherlight thing floating on the breeze. “I mean, he’s just somebody I fell in love with when I was 24,” she tells me, echoing a line of Arthur’s in the movie. What if, Arthur asks Nora as they lie in bed, she had met some other man at a residency who’d read all the same books as she and could comment on her work? But, she says, she met him. And that’s not how life works. “Him being a white Jewish guy does tell the story of what Nora’s life is,” just as Song’s own partnership does. “When I was a playwright, so much of theater was filled with guys who look like my husband,” she says. “That’s who they are. I don’t think I knew many Korean or Asian American straight men in theater. The culture is white supremacist. And misogynist. So it’s going to be built into us.” Past Lives offers a humane vision of how racial hierarchies can ensnare us. “I sometimes talk to younger writers who are in a lot of pain about the fact that they recognize that in themselves,” she says. “And my thing is you have to not only accept it, but you have to learn to love it — not in a celebratory way but in a way you may love all the other parts of yourself you may have complicated feelings about.”

Song and I make our way to the street where Nora takes her final walk in the movie, away from one man and life toward another. The sun is dropping like coins through the leaves, and I can see all the beauty of a perfect East Village block—a brick-red door, a stone archway. Song tells me she assigned her whole team to find her ideal block. Her instructions were clear on what to look for: “It has to feel like nobody has ever given a shit about it. But also it has to feel dreamy. Like the whole film.” On the night of filming the “walk home,” as Song calls it, they had no wind machine, but the wind naturally blew Nora toward one of the men. A crew member asked Song which direction Lee should walk in. The direction would echo her choice in a way. Song told him the direction, then said, as if it were obvious: “Of course. And then she’ll end up right here.”

More on ‘Past Lives’

- Stop Looking for the Challengers/Past Lives Third

- The MFL’s Most Valuable Directors and Least Valuable Movies

- Can Anyone Stop Oppenheimer at the Oscars?