If he hadn’t been sent home after attempting to crash the 1963 Mets spring training in Clearwater, Florida, if his effort to cobble together a professional baseball career hadn’t finally failed, Charley Pride may have never ended up in Nashville.

Sure, he’d already landed several country gigs in Big Sky country, driving up to 180 miles round trip to play shows and make some extra cash after working his day job at a Montana smelter. He’d even been fortunate enough to play on the same bill as country stars Red Sovine and Red Foley. Sovine was so impressed with Pride that he encouraged him to go to Nashville, to pay a visit to the folks at Cedarwood Publishing. “I don’t care what color you are,” he said.

But at the time, Pride didn’t care much for country music, at least not as a viable career path. Even then, the baseball diamond was Pride’s first love, the passion that defined his formative and early adult years. Pride was just turned 13 when Jackie Robinson stepped onto Ebbets Field, completing his crossover from the Negro Leagues to the Majors, and Pride wanted only to follow in his footsteps. From Pride’s vantage, Robinson had pried open a long-shut door to equality and opportunity. Here was a Black man playing in crisp whites for the all-white Brooklyn Dodgers, a man who’d been court martialed in the Army for refusing to sit at the back of an integrated bus, now the apparent embodiment of forward movement.

The window for pro athletes to break big is small, and after a series of injuries to his pitching arm — plus Major League Baseball’s post-Robinson quota system that kept the number of Black players to no more than a handful per team — Pride’s was closing rapidly. After dropping out of school at 15, he’d spent more than a decade bouncing back and forth between the Negro American League Memphis Red Sox and a handful of minor league and semipro outlets, including the team sponsored by his Montana employer. He’d developed a convincing knuckleball when his fastball lost its juice; he’d even learned to switch-hit once he’d learned how elusive curveballs could be from the right side of the plate.

Like any kid reared in the fertile but unforgiving Mississippi Delta, Pride had long learned to make do, to make a way, often out of none. He’d kept himself in the game long enough for this final shot; all he could do was hope that the brand-new team with the .250 winning percentage would let him take it. As it turned out, Mets manager Casey Stengel had no use for the nearly 30-year-old Pride when he showed up to camp unannounced, but Pride’s journey to the South proved serendipitous nonetheless. There was a man sitting in an office 725 miles to the north, waiting on a man just like Charley Pride.

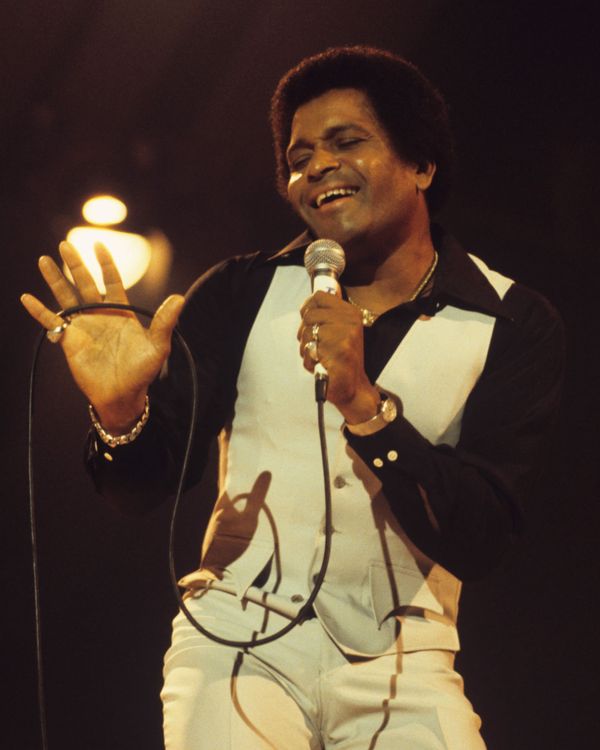

In the aftermath of the December 12 announcement that Charley Pride succumbed to COVID-19 at the age of 86, it is difficult to consider his life and legacy as a country-music icon without considering the environment that birthed his career. He didn’t just show up in Music City as a Black man wanting to sing country music; he arrived in the midst of the ’60s Civil Right Movement, a movement that, in many ways, found its epicenter in Nashville. Students from the city’s HBCUs had launched formal sit-ins to desegregate Music City’s lunch counters in February 1960; two months later the home of civil rights attorney Alexander Looby was bombed, injuring students at nearby Meharry Medical Center and leading to the organization of a march to Nashville’s City Hall. By May of that year, Nashville had officially desegregated public facilities, even as its thriving music industry remained divided by harsh color lines.

Perhaps it was for this reason that famed country music manager Jack D. Johnson set out in search of a Black country singer while working at Cedarwood, and decided to sign Pride when he turned up at the publisher’s door. Perhaps he foresaw that the ongoing push for social justice and racial equality plus the “right” Black country artist could equal lucrative gain. Perhaps he knew that if he wanted to stand out as an up-and-coming Music City mogul, he’d need an artist who would stand out as well.Perhaps Johnson considered both. Regardless, repositioning Charley Pride from former baseball player to burgeoning country music star was going to take intention and a multi-step strategy:

First, Pride needed the financial backing of a record label if he ever hoped to put out high-quality records and get them spun on radio It was a mission that took two years and was only secured when Johnson persuaded guitar maestro and RCA Victor exec Chet Atkins to take a chance on the strapping Black man in the slim suits. Then came song choice. “Just Between Me and You,” which would ultimately become Pride’s first Top 10 hit, was nixed as a first single despite being Pride’s top choice. It wouldn’t work, he was told, because no one wanted to hear a Black man sing a love song to a white woman. The choice, instead, was “The Snakes Crawl at Night,” a song about a man who kills his cheating wife by gunshot and is sentenced to death — a song certainly more aligned with the white imagination.

There were the radio stations who received promo packages that didn’t include Pride’s photo, lest they decide not to play him on sight. And when seeking buy-in from club owners and show promoters, Pride had to convince them he wasn’t there with any civil-rights intentions, that there would be no “trouble” following behind him; then when he finally landed the gigs, he quickly disarmed his audience with jokes about his “permanent tan.” Acceptance from his country-music peers was an entirely separate battle, and when Pride recounts tales of George Jones painting KKK on the side of his car or Willie Nelson nicknaming him “Supernigger” in his 1994 memoir Pride, he dismisses those affronts with relative nonchalance. He instead reframes them, respectively, as a joke, a way to diminish the potency of a wretched slur.

“I didn’t accept the [insults], I just tried to maneuver around them, so as not to get into any confrontation,” Pride told the Dallas Observer in 2016. “I’m not a coward or anything like that, but I think that with the help of my dad and mom, I just learned to find a way around the negative stuff.”

Indeed, he did, and thanks to that thickened skin and willingness to play by industry rules, music fans worldwide were rewarded with decades of his sultry baritone, with hit after hit after hit. From the late-’60s to the early ’80s, Pride netted more than 52 Top 10s, 29 No. 1s, and 70 million records. It’d be a phenomenal track record by any consideration — and one unaccomplished by the vast majority of Nashville imports — regardless of color.

But Pride was Black, of course. And while the white country majority might choose to dissociate his race from his legacy — some remarking how even the most racist of family members still loved Country Charley Pride — the industry that cracked opened its doors to Pride, allowing him to become country music’s first Black superstar, is still hell-bent on reminding Black people of his singularity. Pride’s name is the one trotted out when justifiable rebukes are lobbed against the industry and its history, his achievements upheld as proof that Country Music isn’t as bad and backward as it seems.

Just hours after the announcement of his passing, the Academy of Country Music tweeted their condolences along with a video from their 29th annual awards show, broadcast in 1994. Pride was given the Pioneer Award for his outstanding career achievements that year, and during his acceptance speech, he remarked that it was his first award from the Academy. The clip revealed a glaring oversight from the organization that was created in 1964 to be a more “inclusive” alternative to the Country Music Association, which refused to acknowledge genre contributions from outside the Nashville mainstream. It was glaring, but not a surprise.

Similarly, Pride’s Grand Ole Opry induction didn’t come until 1993; that was two years after Vince Gill was inducted without a single No. 1 to his credit. And then there is the Country Music Association, the industry organization that was created to protect and promote country music as both a genre and marketing tool, carefully cultivating a look and sound that would appeal to both advertisers and media. In essence, it is the organization largely responsible for making country music white and mostly male, and keeping it that way.

2020 is a different year, though. It’s harder to get away with such flagrant whitewashing in the post-George Floyd era, and like every country music institution, the CMA didn’t want to appear marred by the racism it perpetuates. They needed Pride (and Darius Rucker and Jimmie Allen) to stand in as an example of their progressiveness, even as they asked Rucker, a Black man, to sing “In the Ghetto” in tribute to songwriter Mac Davis at this year’s still-in-person award show in November. So, they granted Pride the Willie Nelson Lifetime Achievement Award, an honor that could have rightfully been named after Pride rather than the man who once felt the need to remind Pride that he was still a “nigger,” yes, but perhaps better than the rest. And if he was, then surely Pride should have received the award well before 2020, before a raging pandemic would threaten — and ultimately end — his life.

It is impossible to consider Jackie Robinson’s legacy without careful analysis of his pioneering efforts, and so Pride’s must be given similar treatment. It’s not enough to say that he was first, that he was great, that he was an inspiration to countless Black men and women, boys and girls, who also wanted to believe that they could eke out a career in country. Those things are true, but for the purposes of proper, honest reflection — and with respect to the Black folk who never really had a chance to follow Pride to the top of the country charts — we must also consider what Pride wasn’t. Much in the way Major League Baseball’s restrictions prevented Robinson’s signing and success from bringing a flood of Black talent into the Majors, country music’s still-present barriers have kept Pride’s achievements from triggering an influx of new Black talent. He may have been an icon, a legend, and a hero, but a marker of things to come he was not. As Rucker moves into his position of elder statesmen, Jimmie Allen and Kane Brown are the sole representatives of Black male talent welcomed into the country mainstream. Representing women, Mickey Guyton stands alone and still criminally without a full album released, despite being signed by Capitol Nashville in 2011.

In Robinson’s 1972 autobiography I Never Had It Made, the baseball legend reflects on his career with a despondency that was never revealed in his playing days, one that remains absent from the immortalized image of him we celebrate every April 15. Robinson had come to realize that while his success had meant much for the Brooklyn Dodgers and Major League Baseball on the whole, it meant little for his people. Pride never made such a public declaration, for he, still warmly accepted by country music until his last breath, had an image to maintain. Robinson, on the other hand, ultimately shed any notions that he would continue to go along to get along, becoming a vocal activist for Black civil rights. However, despite their differences in personality and approach, it’s hard not to wonder now if Pride was just as disappointed by the industry to which he’d given so much. For all the abuse that he endured, all the slurs he chose to couch as terms of endearment, his sacrifice never brought transformation.

That’s not to say change can’t still come. Now, more than ever, country music has the opportunity to honor Pride’s life, and death, like they never have before. In the words of Dr. Cleve Francis, a cardiologist turned country music crooner who found his own dreams of stardom dampened by country music’s racism, this is the chance for the industry to get it right: “In honor of this great African American artist, the country music industry should open the doors that have been closed to African American artists for years,” he wrote on Facebook. “Music should be about talent and not color — Charley Pride was that living proof.”