This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

What differentiates comedians from your funniest friend is not that they are funnier. It’s that they can be funny to strangers, on demand. “The difficulty in doing stand-up comedy is not knocking down the pins,” veteran stand-up comedian Brian Regan once told me. “A lot of people can be funny and knock down the pins. It’s setting up the pins that weren’t there to begin with.” Broadly speaking, when people go to the comedy club, they leave their baggage at home; the comedian gets them to be so in-the-moment that they can laugh about trivial problems. So on September 11, 2001, the question facing stand-up comedians was not just practical, but existential. Comedians wondered if people would be able to laugh — not when, if, as in if ever again. They didn’t have to wonder long; stand-ups tend to be pathologically incapable of turning down stage time. Shows stayed on the books, so comedians performed, and audiences came to see them. But imagine trying to joke about airplane food on September 12. Performing stand-up in the weeks following 9/11 was like trying to set up bowling pins on a waterbed during an earthquake.

We are now used to the calm voice of a late-night host after a mass shooting, but in those first couple weeks, people weren’t ready, expecting, or wanting to process what happened. Many comedians didn’t talk about it or simply made a passing reference at the top of their sets. The comedians who did feel an obligation to talk it out were sometimes received positively and sometimes received combatively. Sheryl Underwood was thanked after a show by an air-traffic controller who helped guide United Flight 93, while Marc Maron was confronted by a Marine in the audience telling him “You can’t say that.” Looking back on his first post-9/11 stand-up set, David Cross put it this way: “I would say the audience was not nearly as comfortable as I was talking about it.”

In the following conversations with 37 comedians, the more significant role stand-ups played begins to materialize. Books, movies, and television shows that tried to wrestle with the attacks were written in private, with time to process, but touring stand-up comedians were learning how they felt on the ground. Especially for comedians who make their money on the road, acts are often a collaboration with audiences since material is built each show, each night, based on audience reaction. Many of the comedians took a populist approach. Sometimes that meant a focus on joy and making sure everyone had a good time, but sometimes that resulted in jingoism and Islamophobia. Every comedian’s response to the attack wasn’t necessarily positive, just like every American’s wasn’t. Comedy didn’t save the country after 9/11, but it did reflect it.

In this article

“There’s going to be a war between America and the Middle East, so get ready.”

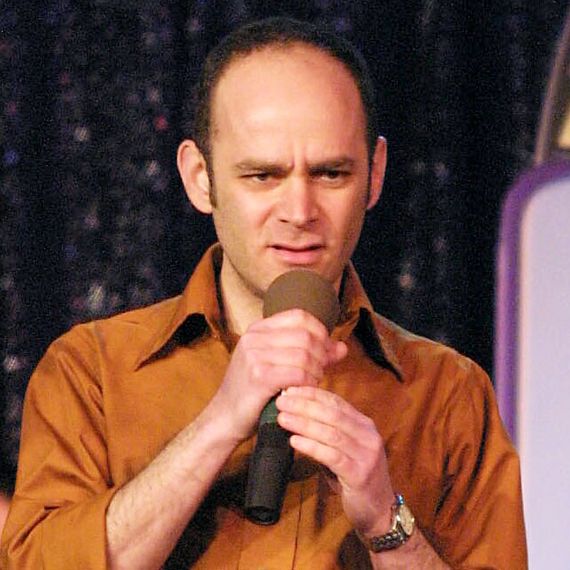

Ahmed Ahmed

Mitzi Shore, who owned the Comedy Store, made me a paid regular a year prior to 9/11 because she had an epiphany that Middle Eastern comedians will be necessary in our society at some point. She would always tell me, “There’s going to be a war between America and the Middle East, so get ready.” I called her the morning of 9/11 and said, “Are you seeing what’s going on?!” And she replied, “I told you so.”

Mitzi decided to open the Comedy Store the Friday after 9/11 and requested for me to go onstage, open the show, and talk about being Middle Eastern and Muslim, to which I replied, ‘Nope!’” I was nervous and didn’t know what to talk about, and she said, “Just be yourself and you’ll know what to say.” So I took her advice. My first joke was “Hi everyone. My name’s Ahmed Ahmed … and I had nothing to do with it. Please don’t follow me out to my car after the show.” That got a few chuckles, then I proceeded into more self-deprecating jokes, and the crowd loosened up.

About a month after, one of the bad things that happened that turned into a good thing was we were booked to play the La Jolla Comedy Store one weekend in San Diego as the Arabian Nights, which was the name [Axis of Evil] originally used. The manager called me and said, “You guys are getting death threats. It’s probably not a good idea to continue with the shows.” I called Maz [Jobrani] and we both chuckled about it, saying, “Well, if we’re gonna die, die laughing.” So we did the shows — which, by the way, were all sold out — and afterwards we were in the lobby doing meet-and-greets, and several white American couples approached us and said, “We had a great time. Thank you for making us laugh. We had no idea your people had a sense of humor” and stuff like that, so it was rewarding in the end.

Two weeks after 9/11, I got a call from the Wall Street Journal, who wanted to interview me. A week later I was on the front page. That article changed my life. Next thing you know we were in all the news publications — mostly political sections, which I thought was funny, but it was the kind of press money can’t buy. This caught the attention of Levity Group, who then pitched the Axis of Evil show to Comedy Central. When it aired, we were the first-ever Middle Eastern comedy show on Comedy Central. We then took the tour to the Middle East and once again made history, selling out 20,000 tickets in five countries: Dubai, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Kuwait. A television network filmed the tour. Once that aired we became instantly famous in the Middle East. It was wild. We would walk through malls or go to restaurants and nightclubs, and people would yell out “Axis of Evil!“ It felt like the Blue Man Group.

“Would the world ever be the same?”

Louie Anderson

After 9/11, I headed to Las Vegas. It was an eerie drive but somehow comforting. I had been working in Vegas since 1984 and was currently working at the MGM Grand — or at least I think I was. Everything was a blur after 9/11, but in Vegas I saw friendly, familiar faces who were as shocked as I was about what happened. We hugged and shook hands as if we hadn’t seen each other in a lifetime. Would the world ever be the same? I stayed there until our show opened back up.

I didn’t even know what I was going to say to the audience when I walked out on reopening night, but it came to me. I’m a descendant of people pleasers, caregivers, and comforters. I used my mom’s adage: “Be nice to people, Louie. You never know what kind of day they’ve had before they’ve seen you.” But I did know what kind of day we all had. We had to go on and not let anything or anyone stop us from living.

I was funny that night but much more thoughtful and comforting to the people who ventured out like I did, and I was also very comforted by them. We have to keep moving, one foot in front of the other, somehow believing things would be better and we would be all right. Little did we know that 2020 was not far away.

“I realized the audience wasn’t looking for my hot take on 9/11.”

Todd Barry

I was in NYC on 9/11. My first set back was at the Comedy Cellar on 9/14. Like everyone else, I was stunned, sad, and confused, but I was so used to performing every night that it seemed okay to start up again. I don’t remember how I addressed the attack in that first set back, but I remember that it didn’t really land. I realized the audience wasn’t looking for my hot take on 9/11. They were fine hearing my joke about buying a wallet at Old Navy, or whatever I was doing at the time.

“I didn’t know if someone in the audience knew someone who died.”

Lewis Black

I was in San Francisco and performed at Cobb’s Comedy Club there the week after 9/11. I felt it was the only thing I could do that actually might help. Most everyone seemed to have stopped performing, and I felt driven to. And I was going to San Francisco, a city that was living a decade or so ahead of the rest of the country, and I felt very comfortable doing a show there. I don’t know if I would have performed at other places.

I had jokes about what was going on around it, but not about the tragedy that had just occurred. I am never quick when it comes to making up a joke after something horrifying or earth-shaking has happened, and there wasn’t a joke I could find that seemed to truly work at that point in time. I didn’t know if someone in the audience knew someone who died or had lost a family member.

The audience was pretty amazing considering what we had all been through. And San Francisco knows comedy; it’s in the DNA of that city. They gave me a lot of space in which to work out what I was trying to say, and they didn’t get uncomfortable when I couldn’t deliver a laugh. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to say or what my act would be that night, so I just opened my mouth and let it rip. I wish I had taped it. After that show, it became a little bit easier, but it took awhile. But it was what I had to do, and it seemed like folks were ready for it before most comics were ready. I wasn’t; I just did it. It was what I had to do — as much for me as for that audience.

“We laughed about how only comics were getting on planes.”

Alonzo Bodden

I remember going to Vegas. I had some casino one-nighter, and I was also doing The Next Big Star, a Star Search type show hosted by Ed McMahon. It was shooting at the MGM Grand. I remember Vegas being empty, deserted. I think they said normal weekend occupancy was over 90 percent, and we were under 25 percent. I joked that Vegas was so empty the hookers were handing out their own flyers. I was also joking at the time that we Black people were glad it was the Arabs because it took the pressure off for a while. I didn’t do jokes about the attack. I joked more about the aftermath.

The crowds loved it; they always do. We comics relieve the pressure, and people were angry. I won Next Big Star, so that was cool. I also remember flying about two weeks after when the airlines just started up. I ran into Doug Stanhope at the airport about 5 or 6 a.m., and we laughed about how only comics were getting on planes.

“It touched me to my core, and I just started talking about what happened.”

Elayne Boosler

Like everyone, I was numb. I was booked to go back to a 700-seat room in Laughlin, Nevada, the weekend of 9/14. Of course, we called to let them know I wouldn’t be coming. They said “You cannot cancel. We’re sold out and no one has canceled their reservation. People are expecting you to come. They need something.” We drove from L.A. to Laughlin. The town has a lot of electronic marquees on restaurants, hotels, on everything. It was surreal driving past them all as they reflected on the tragedy: “God Bless America,” “Pray for America,” “God Save America,” “God Protect Us.” And then the neon sign on the hotel I was about to play: “God Help Us — Elayne Boosler Tonight.” It was the first time I laughed since 9/11.

I remember being in kind of a numb dream state as I walked onstage. Then I looked at the audience. Most everyone was holding hands with the person they came with. The looks on their faces were so hopeful, so expectant. It touched me to my core, and I just started talking about what happened. I started making jokes about Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson blaming gays, the ACLU, and abortion for God letting the attacks happen. I remember the jokes were pointed, but my delivery was more gentle. Slowly I got to my regular material, and the laughter was wonderful. People were so grateful to be able to forget for a bit, and I know having to focus and perform snapped me out of my despair probably weeks before it would have happened naturally.

“I remember feeling like a superhero in that moment.”

Gina Brillon

I think it was about a week or two after 9/11 that I decided to get back to the clubs. I was afraid people would be too sad to laugh. It was such an emotional experience. There was such a feeling of connection in New York at that time that I wanted to keep it going. It seems like the climate was all about us leaning on each other to help heal from this tragedy.

The audience was just as afraid as every performer getting onstage. The climate in New York felt like one giant nerve that you were afraid to touch. You could look at the audience and see how tense they were. It felt like they were asking themselves, Is she gonna talk about it? I could see in their faces this thought or feeling of Please don’t bring it up.

What I remember most is the feeling of relief — it was like the audience took a huge sigh of relief after my first joke hit. Once they started laughing, it was such a release. So much energy had been pent-up — so much pain, anxiety, sadness, and worry. That first laughter just felt like the world had been lifted off of their shoulders, just for a moment. I remember after my set, I was standing by the bar, and this gentleman came up to me, and he said, “I want to say thank you. That’s the first time I’ve laughed in weeks. Thank you for what you do.” I remember feeling like a superhero in that moment. Somehow I had healed a person without touching them or without being a doctor, and it was the best feeling, especially during that time.

“It will always be too soon.”

Michelle Buteau

I worked as a local news editor during 9/11, and truly it felt like I was editing a real-life horror movie. When I decided to do stand-up seriously, it was days after 9/11. I’m so glad I got onstage, because it felt like an outlet I needed; it felt good to laugh again. Most of my stuff was self-deprecating “I’m so big-boned, isn’t that wild?” type shit, but I didn’t care.

I didn’t talk about that day onstage because it was too soon. It will always be too soon. I’m really so grateful that I found my voice in the midst of a terrible, traumatic, strange time in the world, but I don’t think it should come to that for people to live their dreams.

“The audience was not nearly as comfortable as I was talking about it.”

David Cross

I knew I wanted to go onstage and talk about it as soon as I could. I felt fine about it. I saw Marc Maron a couple of weeks later at Luna Lounge, which was the first place to open back for shows, say, “Can I talk about 9/11 yet?” and the audience responded enthusiastically. And Marc wasn’t being snarky or asking hypothetically — he truly wanted to know, “Is it okay to talk about yet for you guys?” I asked him if I could use that when I did my next gig, which was in a couple of days at Northwestern University. He said “of course” and I did, and pretty much got the same response.

I then just … talked about it, trying to find jokes along the way, most of which made it into my album [Shut Up You Fucking Baby!]. I would say the audience was not nearly as comfortable as I was talking about it, but they were a good, attentive audience, and it ended up being a pretty good set that felt like a minor accomplishment.

“I don’t think to this day I’ve ever, even indirectly, really cracked a joke about it.”

DeRay Davis

I remember being in L.A. I was laying in bed, and then my brother comes in the room: “Wake up. Wake up. We’re being attacked!” Then he turned on the TV for me. I’m in disbelief; I’m lost. I’m thinking, What went wrong? Because everybody’s like, “This is a direct terrorist attack.” I had never really heard those words other than in history. I was supposed to go to New York. I was like, “Wait, do we still go to New York? Is New York still alive?”

Getting back onstage was immediate. It’s the only place we have; it’s our only therapy, so I’m like, I got to get onstage and at least do some Q&A, listen to people, talk to people. So I probably was up within the next three days. It was very, very sad for everybody. You felt incomplete. You felt like one of the states was missing, and I wondered about the comics in New York.

I couldn’t find a joke in it. I always think of the craziest shit — like I laugh at kids falling all the time, I laugh at old people who things don’t work out for, because I assume they must have lived a fucked-up life. So I knew there was some form of paralysis in my thought process, of coming up and trying to heal people from it, because it was so intense.

I think the main reason I couldn’t find a joke in it is because I imagined if I had a family member in it. I don’t think to this day I’ve ever, even indirectly, really cracked a joke about it.

But audiences showed up, because audiences needed it, and they needed more outlets other than just CNN. They want to see what people are talking about, and the best place to go is to a comedy club.

The biggest part of it was the fear that you can be touched. Here we thought we were untouchable. Here I walked around doing comedy anywhere, and I’d sat next to people and seen people get stabbed, seen people get shot, seen all this horrific stuff happening around me, but it still felt in my control. When you have no control, that’s when it’s scary, so I think that was my main thought for everywhere I went after that.

“That was the first time in my comedy career that I was like, ‘Oh, you can do that.’ ”

Joe DeRosa

On the one-year anniversary of 9/11, I had been doing stand-up for a year. I was at the Laff House [in Philadelphia] doing the open mics, and I remember it was such a big deal that it was the first anniversary of “Never forget.” So it was in the air big time, and everybody’s going up onstage, and nobody’s mentioning it because we’re all open micers. It’s hard enough trying to figure shit out, and then you’re also like, Well, I don’t want to piss off the entire audience by accident.

Then this kid, Sean Clay, went up and did a joke where he goes, “I appreciate what the firemen and cops did on 9/11, but stop calling them heroes … Heroes? Spider-Man’s a hero. Batman’s a hero. These guys are firemen and cops.” And it got a laugh. That was the first time in my comedy career that I was like, Oh, you can do that — you can go into a hairy subject matter and take it one way, where they think they know what you’re going to say, and then you switch it, and you actually get them to laugh about it.

The hackiest thing you could have done in the years that followed 9/11 was have George W. Bush jokes, and everybody had them. They were the original Trump jokes. This burst of new vehemence did occur — 100 percent did occur — but you were allowed to not participate in it; you were allowed to say, “I don’t want to do Bush jokes.”

Back in those days, you could go to a comedy club, and you’d see a guy like Nick Di Paolo followed by somebody like Janeane Garofalo with painfully different perspectives, and then you’d see them talking after the show. And I feel like that, somewhere along the line, since 9/11, has gone away. I do think that 9/11 lit the fuse for that, and I think COVID put the icing on the cake. But maybe I’m looking back with rose-colored glasses because I was younger and there was more excitement and wonder to the world.

“Were there a handful of people that didn’t like it? Of course there were.’

Jeff Dunham

A year later, we were still looking for Osama bin Laden. Nobody knew if he was alive or dead. So where’s Osama bin Laden? I suddenly had this thought one day: I know where he is. He’s half-dead, he’s undead, he’s a skeleton, and he’s been hiding out in my trunk with my other characters. So, I started piecing together the Dead Osama [character], and for the material, I sat down and I thought, Okay, I’m going to pretend there are relatives of people who directly lost loved ones in the 9/11 attack. What would be funny to them right now to help them move forward and to also get the big laughs?

So I wrote that material, and then I thought, Am I going to head to Hawaii or Alaska or somewhere and try this out gently? No, I’m going to go where it counts. I was booked at Bananas Comedy Club in New Jersey, six miles from Ground Zero. It couldn’t have gone any better. From then on, for a couple years, I did that routine almost word for word, all throughout the country.

I used the Dead Osama [character] for maybe a year and a half, two years. And sure, the hunt for him was still on, but Osama just kind of went out of the news, so, it became old material and the character wasn’t really relevant anymore. But what is relevant? Well, the threat of terror, and the idiots that did that. That’s still in peoples’ minds, because we’re all having to deal with all that stuff at the airport and all those things that everybody could relate to. So I said, “Boy, there’s a lot of material there.” So I created Achmed the Dead Terrorist. I had on good authority that people in Iraq, businessmen, were sitting around at lunch saying to each other, “I keel you.” Were there a handful of people that didn’t like it? Of course there were.

“When I started doing sets, I ignored the attacks. That was my strategy: Just get laughs.”

Wayne Federman

I was living in West Hollywood, and saw the plane hit the second tower live on television. The fear was that what had happened in New York City was only the first wave. On that day, I purposely didn’t call my friends and family back in New York, thinking it was best to keep the lines open. They were still searching for survivors.

There were inappropriate jokes that comedians told just amongst themselves — I recall one was about how the terrorists picked the worst flight school. The clubs stopped doing shows, and when they returned, the crowds were extremely sparse. My sense was they didn’t want to hear 9/11 jokes but were more looking for a distraction from the non-stop news coverage.

When I started doing sets, I ignored the attacks. That was my strategy: Just get laughs. At the top of my set, I would say something soft and benign like, “Just wanted to make sure we all know where the exit signs are.” That was it. But I don’t do topical or political anyway.

I did notice that on that multi-network TV special America: A Tribute to Heroes, broadcast ten days after the attacks, that it was only musical performances and serious speeches. And it struck me that, in this circumstance, comedy just wasn’t on the same level as music. Then Letterman, Daily Show, SNL, and of course The Onion put out that great issue. So I recall it took about three weeks to get stand-up back.

“I did not think, at the time, it would be good to be onstage.”

Marina Franklin

I was home. I live in Harlem. I did not think, at the time, it would be good to be onstage. I thought, honestly, nothing was funny. I hung around the comedy clubs a lot as a beginning comic — places like the Comedy Cellar, Boston Comedy Club, and the Comic Strip Live. I was still getting people in the room by standing on the street and doing what they called “barking.” That did not seem to be the right thing to do at the time.

One night, I was hanging out at a club, and a comic I knew well was fighting with a customer over doing material about September 11. The customer was told they were in the wrong, and afterwards I merely suggested to the comic that the timing was too close and possibly people are raw with emotion. This was the week of — maybe even a day after. I was shut down immediately for saying this. The anger from this comic was too much for the moment, and I guess I hit a nerve. It was strange because I didn’t tell them not to do it, I just thought the audience member that was upset had a right to be upset because nothing like this had ever happened before. The comic told me that I am not a real comic for saying that. I cried. One of the waitresses admitted that the comic was being too harsh. It was a moment that possibly defined how I approached topics that are raw culturally.

‘I was ruthless!’

Adele Givens

Since I was working on The Hughleys, I didn’t do a lot of stand-up dates, so when I finally got the opportunity to try some material related to the 9/11 attack, I was ruthless! By then I’d seen way too many videos looped by thirsty news outlets, and my comedic irony observation was on full alert.

My very first ironic observation was that on 9/11 nobody rang the emergency-broadcast system alarm. We’ve practiced it and heard it on television so much that we could recite it: “THIS IS A TEST OF THE EMERGENCY-BROADCAST SYSTEM … THIS IS ONLY A TEST!!” But when the actual emergency happened, we froze! That joke actually worked very well. Thinking back, I believe we all needed a place to put our frustrations about the situation, and that was a perfect and fitting place. After all, we never did hear any warnings, did we?

“If I didn’t want to laugh — someone who lives and breathes jokes — how was the audience going to feel?”

Judy Gold

I gave birth to my son Ben on August 9, 2001. I was back onstage within three weeks. The clubs were closed on 9/11 and several days following. On September 13, Ben had a 104 fever and was very ill. The pediatrician sent us to NYU Hospital for a spinal tap. I stayed with him because I was breastfeeding, and I’m a Jewish mother who wasn’t leaving her child’s side. I remember saying to the nurse, “Is it busy?” and she replied, “We wish.” We left the hospital four days later on September 17. The outside of the hospital was covered with photos of the missing and contact phone numbers. It was heart-wrenching. Rosh Hashanah began at sundown, and as I walked into my apartment, I started feeling very ill. I caught whatever Ben was sick with. I recovered and got back onstage the following week.

I went to Stand Up NY on West 78th Street. It is in my neighborhood, so I was only away from Ben for about an hour or so. I remember thinking, Is anything funny anymore? The feeling of sadness and hopelessness was so palpable everywhere in the city. And every single building was papered with photos of the missing. If I didn’t want to laugh — someone who lives and breathes jokes — how was the audience going to feel? But I knew if I waited any longer, it would be harder to get back onstage. I was ready to figure this out.

I remember talking to other comics about how we couldn’t do any George W. Bush jokes anymore. We all had W jokes. He was a treasure trove of material, but at that time it seemed un-American, unpatriotic, disloyal to disrespect the POTUS. I’m always prepared, but there was no way to prepare for this. I’ve always been able to disarm an audience, but for the first time in many years, I was the one who was feeling disarmed. I had rid myself of my usual comedy weaponry. So I chose to open with some tried-and-true material, but once I stepped on that stage and looked out at the faces there who were hoping for an iota of levity, I knew I had to address the gigantic elephant in the room. That is the job of a comedian.

I started talking about all the jokes I couldn’t do because everyone loves George W. Bush now (Remember, this was on the Upper West Side). I talked about having a new baby — now I was a mother of two — and I did some material about my mother. I remember the audience responding well, but we were all broken and scared. It wasn’t until after the night of September 29 when SNL aired and [Rudy] Giuliani — way before his complete and utter meltdown — gave us all permission to laugh again that things in the comedy clubs felt closer to normal again. 9/11 was the epitome of “too soon.”

“I wanted to be the first one to address the elephant in the room.”

Gilbert Gottfried

I was booked for the Hugh Hefner roast. Somewhere between me being booked and the actual roast, September 11 happened. A lot of guests either canceled or could not get flights. We were going through with the roast anyway. Around that time the entire world was shocked, particularly in New York where you could see and smell black clouds. Oh, and did I mention that the Hugh Hefner roast was taking place in New York? Well, it was.

Now, if there is something that should not be said, I like to say it. As I am standing at the podium, I wanted to be the first one to address the elephant in the room. So, after a few jokes at Hefner’s expense, I said — and I quote — “I have to leave early tonight. I have to catch a flight to L.A. I couldn’t get a direct flight. We have to make a stop at the Empire State Building.” Well, no one in the history of show business has ever lost an audience worse. There was booing and hissing. One guy yelled out “Too soon!” which I thought meant that I did not take a long enough pause between the setup and the punchline.

Well, after standing there for what felt like 500 years, I decided to go to the bottom level of hell. I told the Aristocrats joke. If you know anything about that joke, it’s beyond offensive. It has to do with loads of incest and bestiality, and those are the clean parts. To my shock, the audience went from brewing and hating me to laughing uproariously. The laughter just kept building. When I got to the punchline, people were cheering. One review said “It’s like he performed a mass tracheotomy on the crowd.” What that show proved to me is that after horrible times like September 11, people desperately need to laugh.

“It seemed to me that the way you fight terrorism is: Whatever it was that bothered the terrorists, do it more.”

Penn Jillette

In any sort of disaster, everybody does what they do more. The generals want to do war more. The politicians want to do politics more. And the free-speech people want to do free speech more. Teller and I said, “What can we do to help free speech here?”

We’d been asked to do Rocky Horror on Broadway, and it was not in our plans at all. And I forget who it was, but somebody said, “Broadway is doing awful, and they’ve asked you to come in and do a week or two of Rocky Horror, to add your names to that, to get people into a Broadway show.” And I said to Teller, “You know, the terrorists were religious, anti-sex, crazy people, and what I want to do more than anything is put on garter belts and dress in drag, in a just friendly way. I just want to send that ‘Fuck you’ out to the world that just says, ‘Oh, you don’t like sex? Well, then I’m going to go on Broadway wearing garter belts. Fuck you. If you need me, I’ll be wearing fishnet.’” The way terrorism is supposed to work is that people get scared, and it seemed to me that the way you fight terrorism is: Whatever it was that bothered the terrorists, do it more.

Although we were doing all this freedom-of-speech stuff in our ancillary work, in our primary work, it was probably the first time that I was just saying to people, “I do a magic show in Vegas.” Before that, I always wanted to say, “We do a magic show that’s different in this way and this way and this way, and we have intellectual ideas that we work in.” I didn’t want to do any of that. Teller and I came back doing the most old-fashioned magic show we’ve ever done. We just did tricks that would really fool people, and we told jokes that would really make them laugh. And the whole show felt light and breezy.

We had a thing about the flag and patriotism in our show, and burning the flag and freedom of speech. We took that out. We had a thing in our show with guns. We took that out.

I really wanted people to say, “Jeez, we went into that theater, and we came out 90 minutes later, and for that 90 minutes, we laughed and saw tricks that amazed us.”

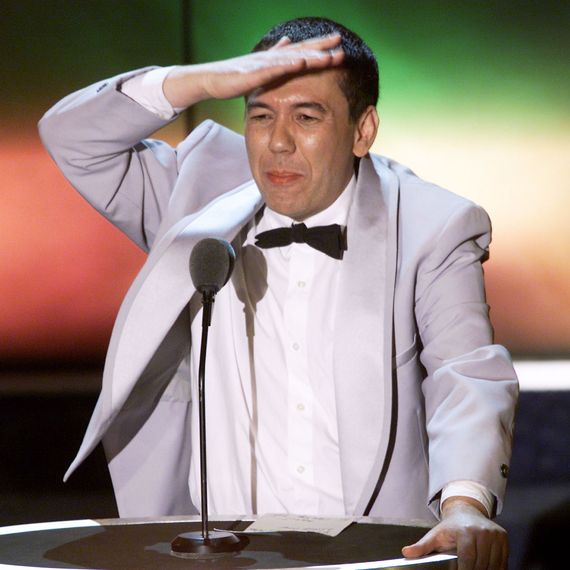

“I think our voices became more and more important.”

Maz Jobrani

Either the following Saturday or maybe two Saturdays after, I had been hired to do a private event at someone’s house in Irvine, California. Irvine is pretty notoriously red-state-y. And I called this guy and said, “Hey, I don’t know if it’s a good idea if I come to do my show. How can you be funny now? And with my background, I feel like I’m coming into the dragon’s lair.” And the guy was like, “No, you should come. I think people will need to laugh. It’ll be good for everybody. And listen, just if it makes you feel any better, my wife is actually Turkish. So she’s from that part of the world as well.” That helped me feel a little more okay.

I flipped my act so that I did not lead with being Iranian. At one point I said, “Oh, by the way, I’m Iranian,” and then said something along the lines of like, “Yeah, I know. I’m disappointed too.” Meaning, Hey, I didn’t have anything to do with it. I felt I had to tiptoe into that portion of my act because of my fear of having some sort of retribution. The difficult part of the show was not that it was necessarily that there were like a bunch of racists standing there staring at me. It was the show being at a fancy home in Irvine, outside by a pool, which is not the best for comedy acoustics.

I remember I bought an American flag and put it on the back of my car. I don’t know if it was out of fear of having somebody shoot me or if it was out of patriotism; it was probably out of both. I was pulling into the parking lot of the Comedy Store, and there was this comedian, Marilyn Martinez, who’s passed away since. She just was laughing at me in a funny way. She was like, “Oh my God, look at Maz Jobrani. He’s got his flag to try and blend in,” and I go, “Hell yeah, Marilyn. I’m blending in!”

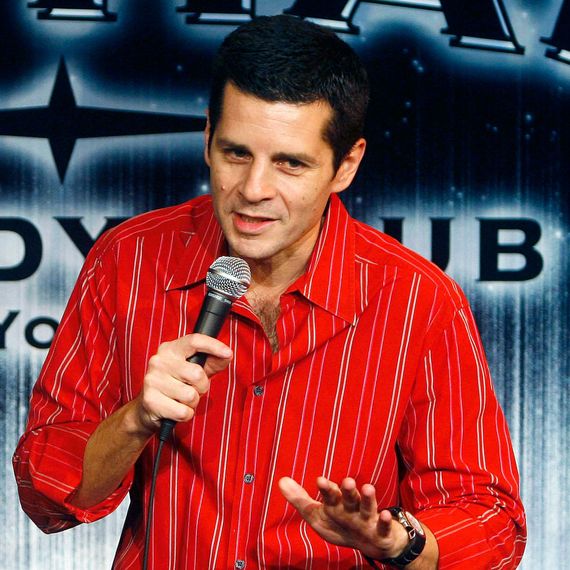

“I was kind of hoping — maybe it was a little bit of a pipe dream — that they would come to our defense.”

Aron Kader

I’d started stand-up in ‘99, so I was barely two years in. For somebody at my level, I didn’t have enough experience to totally know what to say and how to handle it, so I just went to the Comedy Store to hang around and watch how other people handled it. My first reaction was: Go onstage and just do your relationship jokes, and don’t talk about being an Arab. I bombed. In October, I was doing a local spot on some Spanish network, and I was afraid to just go, “So I’m Palestinian. My family’s Muslim.” So I did the relationship material — and bombed.

After that show, I said, F this, I’m just going to do what I’ve got to do. I can’t pussyfoot around it. And as soon as I went back to the exact same material I had before, it was like it was new. It was really weird to feel like this material has new life because of the audience — not because of me, but because their perspective had changed so much. As soon as I realized that the audience was going to have a different respect for my same old material, I was like, Well, I’m ahead of the curve.

When you start out, people will tell you, “You’ve got to be comfortable with the silence. People who are comfortable in the silence are always the better comedians.” And it was in that silence that I was noticing there was this curiosity, this fascination almost. Then the reactions started to come back: “This is cathartic. This is catharsis. People need this.” People need to put a face or a voice to the enemy, for a lack of a better word.

You could feel a bit of tension with other comics being like, “You should just say you’re Italian,” or “I wouldn’t do that” — just being a little bit critical or, even to this day or years after 9/11, it was almost a little bit of sour grapes by comedians: “Well, I can’t just get up there and talk about my ethnicity, because I’m just white.”

Every ethnic group — or fat, or gay, or whatever the thing was — they all had their sort of “things” onstage. So sometimes I was offended that they didn’t talk about stuff, or that they weren’t curious or that they didn’t want to approach anything about the subject. It was like, Geez, everybody’s just going to ignore this? Are us Arab comedians going to have to do everything? Everybody was so tentative or afraid or just didn’t know how to do it.

I remember [Carlos] Mencia was onstage at the Comedy Store, and he said something like, “Arabs, get on the back of the bus.” Like, “Hey, we waited our turn, and you guys just blew some shit up, so what do you expect? Get the fuck on the back of the bus.” I was in the back of the room, and I literally just yelled “Boo!” I was just waiting for him to get offstage and I go, “Hey, Carlos, what’s that about?” He goes, “No, no. That’s not what I was saying.” I’m like, “You literally just told us to get on the back of the bus.” “No, but what I was saying there is …” And I was like, “Come on, man. You can’t be an ethnic comedian and be asking for sympathy for your group but then act like a moron.” It was just hypocritical.

So there was a bit of that from Black and Latin comics, where I kind of was hoping — maybe it was a little bit of a pipe dream — that they would come to our defense a little bit. When there’s a group that doesn’t have a voice in comedy, you would think that you would find support among other minority comics that would say, “Yeah, you guys got to do this.”

“I don’t like that it takes stuff like that for us to come together, but there it is.”

Jackie Kashian

I live in Los Angeles, so I woke up to people yelling into my voicemails to turn on the TV. I spent the day with friends watching TV. It took five hours for the comics I was hanging with to start making jokes. Not about New York. Not about the dead. Not even hacky about the Saudis. The first joke I remember was when L.A. decided to lock down Disneyland — to lock down Warner Brothers and NBC. My buddy sighed, “Los Angeles, it’s not about you.” And it was the first laugh.

An hour later I got a call to do a show. The booker said, “A bunch of people canceled. You willing to go up?” So I picked up a set that night. No one joked about it; we all did our most polished stuff to give the people in that coffee shop a laugh. Just for a minute. Like the pandemic, people rose to the occasion to help, to cheer up, to support. I don’t like that it takes stuff like that for us to come together, but there it is.

“The consensus seemed to be that these people were freaked out.”

Laurie Kilmartin

I performed either 9/13 or 9/14 at a youth hostel in Harlem. The audience was mostly young Europeans who were now trapped in the U.S., since all flights had been canceled. I think the only reason the hostel had a comedy show that quickly is that almost no one in the audience were New Yorkers or Americans. Even so, I remember that everyone looked stunned and tired. I believe Jim Norton was onstage when I walked into the room. I was wondering if he would mention the World Trade Center; he did not. In fact, I think I walked in on a dick joke, which was a huge relief.

As for my own set, I remember doing road-type stuff, including more dick jokes. The consensus seemed to be that these people were freaked out, some of them don’t speak English, so keep the comedy as stupid as possible.

“How can an entire mood be dead — and why?”

Jen Kirkman

I can’t remember how soon I got back up — maybe two weeks? I wasn’t a headliner yet nor doing comedy for a living. I had been doing comedy for five years and was working a day job that I hated in NYC.

I felt okay about it because I saw other comedians getting back to it. The famous alt-comedy show Eating It at Luna Lounge was packed the first night back, and I saw Marc Maron and Janeane Garofalo do great jokes and observations making fun of Giuliani for telling us to “go shopping” to handle the aftermath, and how ridiculous it was that America was falling for him as “their mayor.” It felt subversive to even watch live comedy. I felt fine going back onstage as well, because one thing that everyone was united on was that a terrorist attack can’t stop our way of life. We can’t be scared into staying home or thinking it’s inappropriate to laugh.

One thing I remember from this time was the media pushing the narrative that we can’t let the terrorists “win” by not going out and living life, which I get on one hand, but it was really a right-wing talking point to further make us think that we were attacked because they hate how Americans gather at bars. And yet the media was also pushing this opposite narrative that “irony was dead” after 9/11. I never understood what they meant. How can an entire mood be dead — and why? It seemed stupid. Just because some sincerity had been injected into our blood doesn’t mean we were post-comedy.

“You had to get back and laugh.”

Martin Lawrence

Some weeks after, I played NYC and donated all the money to the NYC rescue. Shortly after, I played D.C. and donated to the Pentagon, since I come from a military family. You had to get back and laugh, but you had to do it in a respectful way.

“We were living in the sort of body-dust cloud of that event for months, so there was no ‘too soon.’”

Marc Maron

What I remember is the way [the Comedy Cellar] felt. Nobody was secure in their sense of reality, and people were clearly freaked the fuck out. It was like shock. The laughter was quick and weird. Clearly what we were doing wasn’t really a comfortable or effective show. It was just doing something, because at that point, Lower Manhattan was closed. It was constant police activity and excavation activity. People were sleepwalking in a state of profound shock, so that was your audience. And if you’re like me — who’s not going to be immediately jingoistic or patriotic in the classic sense, and is going to sort of explore things as a reactive liberal person — it was dicey.

For me, comedy was a way of processing whatever my sense of truth was and my sense of righteous indignation. I saw comedy as a platform that you worked through things on. For me, the challenge was: How do we make this funny? How do we make this relevant through comedy? It’s sort of our duty to try to disarm this a bit and process it so people can move through their fear and anger to a degree. I didn’t feel like I was entertaining the troops; I felt like, We’ve got to process this collectively, and it’s going to go through me, the way I do it. I felt like it was my social responsibility to get to it. We were living in the sort of body-dust cloud of that event for months, so there was no “too soon.” That smell lasted for months, it seemed like, and you were just sort of like, Is that hole still burning half a mile away? They were pulling pieces of people out of there for a year. There was no way to not be in the shadow of it. There was a tension.

“Those weeks and months that followed, I admit, I was proud I was a comedian.”

Bonnie McFarlane

On September 10, 2001, I did a stand-up set at Largo in Los Angeles. I had a good set, drank too much, and went home long after I should have. I set my alarm to wake me up with just enough time to shower and get to work 15 minutes late. But my alarm didn’t wake me up. My phone did. It was relentless. After ignoring the first 700 rings, I finally picked up. It was a receptionist from the production company I was working for. She told me that I didn’t need to come in for “obvious reasons.” The reasons weren’t obvious to me. I didn’t have a TV and the internet wasn’t available on cell phones yet, so I just went back to sleep. But my phone. It. Just. Kept. Ringing.

A little less than an hour later, I was at my neighbor’s apartment staring at her TV as the horrific events unfurled on an endless loop. And then, after seeing the towers fall all day, I got a text from another comedian: “We’re still on for tonight.” She meant the comedy show I was booked on — the one in the basement of a bar that didn’t get more than a handful of audience at the best of times. But here she was determined that, despite the somewhat catastrophic events that were taking place, the show must go on. I ignored her. But later she texted again: “Some people think we should cancel but I think if we don’t do it, the terrorists win.” I never texted her back.

After a few weeks, I did start doing stand-up again. People were going back to the clubs — not in droves, but in trickles. Comedians started figuring out how to once again get laughs and how to not take it personally when they didn’t. And slowly, as a nation, we cried less each day. Those weeks and months that followed, I admit, I was proud I was a comedian. It felt like I was contributing something. I felt like maybe this job was important after all. Maybe I was helping people. But I’m glad when people ask me what I was doing on 9/11, I don’t have to say, “Talking about bad dates in the basement of a bar so the terrorists wouldn’t win.”

“Everyone was on edge. It felt like disarming a bomb.”

Jerry Minor

My vague memory is doing the ASSSSCAT show at UCB Theater on 23rd and 6th. I was living above the theater at the time and making plans to go back to L.A., where I had been living before moving to New York. I had just been informed by SNL my contract wouldn’t be renewed, I think, a mere days before, after a long summer of it being up in the air. I was so ready to go back to L.A. where I had made roots and to get back to work in my comfort zone.

9/11 hit on a Tuesday, and I was scheduled to go back to L.A. on that Thursday. So no planes left that week and I was stuck in N.Y. I’m not sure when we did the show, but it was definitely the first show in the theater since the attack. David Cross was the monologist, and everyone was on edge. It felt like disarming a bomb, because everyone was so afraid of saying something inadvertently referring to the attack. It was the most awkward show. It took a few months before I was comfortable onstage.

“On September 10, I went to sleep a white guy, and on September 11, I woke up an Arab.”

Dean Obeidallah

On 9/11, I was with my girlfriend who lived on 8th Street and 6th Avenue. I was working at SNL on the production staff, and we had already started going in for work because our first show was coming up. I woke up and turned on the TV, and we heard reports that a plane accidentally crashed into the World Trade Center. Then it became clear it was much more than an accident.

I was not thinking about comedy. I just knew that this had been some kind of attack, and being of Arab heritage, obviously I had to wonder if we were going to hear this was some kind of Middle Eastern terrorist attack and turn out to be my worst nightmare of that. So it was different than most comedians; most comedians are just like, “It’s a horrible attack on America.” Of course I shared that, but then secondly, I worried, If they do share the same heritage as me, how does this impact my community and people who look more Arab than I do? Because I’m mixed — I’m half Palestinian, half Italian, and people don’t tend to guess I’m Arabic.

Then, I think a few days later, we came back to work at SNL like, What’s going to happen? It was brand-new territory for all of us. I think my first stand-up show was only a little over a week later at Stand Up New York. The audience laughed inappropriately loudly. It was not a comedy show, it was a therapy session. It felt like they were hugging us with their laughter. I’ll always remember how the audience laughed in ways that were not at all linked to how funny the jokes were, but more linked to how much they needed the release, and how much on some level it was therapeutic for them.

The manager at the time said to me as a friend, “I don’t think you should use your real last name onstage.” Obeidallah is a very Muslim name. “Servant of Allah,” “serving God,” is what it means in English. He goes, “I don’t think you should do any jokes about being Arab onstage.” I thought about what he said for a couple of days before I went up, and at the time, there were people getting attacked. My own cousin was attacked. I went onstage using “Dean Joseph” for like a week there and a couple other places. Then after a week of doing that, I went back to Dean Obeidallah.

There were incidents with comics. I don’t want to say their names. One comic was literally doing a joke that was like “punch your cab driver in the back of the head and feel more American.” I went up to him and said, “You’re actually encouraging violence against brown people.” He was like, “It’s just a joke.” I’m like, “You’re encouraging violence. It’s not.” I don’t think we talked for years. There were hate crimes spiking, so a joke like that was really dangerous. And people were laughing, the crowd was cheering, and you’re like, That’s frightening.

I didn’t talk about being of Arab heritage for like six or seven months. I didn’t know at the time how to talk about it in a way that was going to contribute to any kind of conversation on the backlash against Arabs, and I was not really in touch with my heritage too much, to be honest. I did a whole one-man show at the Fringe Festival five years later about how on September 10, I went to sleep a white guy, and on September 11, I woke up an Arab. That’s a shorthand of my life. I now identify as an unapologetic minority. I view everything — the news, my world, everything — through the prism of it as a minority now. That took years. I wanted to remain a white person. I joke that the 20th anniversary of me no longer being white is coming up.

“I knew, right as I was it, that comedy was going to suck for a while.”

Patton Oswalt

I was onstage less than a week later. At the time, Blaine Capatch and I were living in the same building on Normandie [Avenue in L.A.], and the morning of 9/11, Blaine woke me up with the scariest phone call I’ve ever received. It was 8 o’clock in the morning on the West Coast, and there’s Blaine’s voice in my ear after I answered, saying, “Turn on the TV, man.” I asked what channel, and he said, “It doesn’t matter,” and then he hung up. The walk from my bedroom to the TV in the living room was eighteen nightmares in as many steps. Click on the TV and I’m living in a different world.

I was onstage at the Largo the next Monday, the 17th. I’d had six days to be, variably, hopeful and stupid (Maybe we’re going to evolve past celebrity culture and organized religion), angry (Those fuckers), paranoid (That didn’t happen, I’m still in this bad dream, I’m not really walking down this hall in my building, it’s Monday September 10 again), and then terrified (Bad people are gonna run with this).

So when I hit the stage that Monday, I was the least present I’d ever been as a comedian and as a person. So was everyone else. No one didn’t talk about it on that show. I think Sarah Silverman and Kevin Seccia went up. I can’t remember anyone else. And I can’t remember too much of what I said, except at one point, out of nowhere, I just blurted, “I keep seeing people say the hijackers are all religion and violence. And they are. But we’re the bloated, late-’70s Zeppelin and Emerson, Lake & Palmer of religion and violence. These guys are the Ramones. They’ll carry their own amps while we’re arguing for bigger fog machines.” Something like that. There was a lot of fear and self-righteousness, and I knew, right as I was saying that, that comedy was going to suck for a while.

“The country was so full of confusion and anger.”

Greg Proops

The weeks after 9/11 were tempestuous, to say the very least. The country was so full of confusion and anger. A comic is supposed to sort through all that and find humor and common ground. Not an easy task for us, or the audience, who were looking for release.

My first sets were in England a month afterward. The flights and airports were eerily empty. The U.K. crowds were also out of character by being most sympathetic. English crowds have a pathological hatred of sentiment. But I found by making fun of our innate self-absorption and W’s obvious weaknesses, illiteracy, privilege, inarticulateness that we could find some humor.

The act of terror was not lost on British crowds. Having lived there in the ’90s, I experienced the constant awareness of car checks, not leaving bags in dressing rooms, and random bombings that were a weekly occurrence. The common ground is where the humor lies. Tragedy shared is the mother of empathy, and empathy leads to laughter.

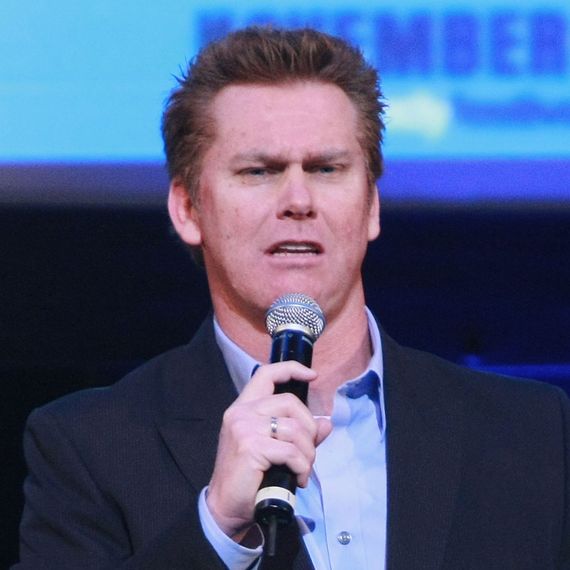

“No, comedy is important too. Everything that used to be is still important.”

Brian Regan

I was in Las Vegas the morning of 9/11 for a corporate show that I was supposed to do that day. That, obviously, got canceled. A week or two later, I had a show at the Improv comedy club in Irvine, California. I remember driving down there, thinking, This is crazy. Is there going to be anybody in the audience? Are they going to think that this whole thing is callous or we are uncaring for trying to be funny under these circumstances? Then, when I got there, I walked into the club and it was packed, and I don’t think it was because of me, necessarily. I think it was just because people were ready to just have something normal going on in their life.

When onstage, I just acknowledged the situation. I don’t remember exactly what I said, but the gist was, “I know everybody in this room knows what went down a week ago, and obviously we’re not here to make light of that tragedy, but obviously we’re here for a reason, and hopefully we can have some laughs tonight. I hope everybody here has a good time.” Everybody gave me a big round of applause on that, because I think they were all thinking the same thing.

People were ready to laugh, man. But I remember being onstage also recognizing, This isn’t all about comedy. This is about people wanting to express themselves in a way other than how they’ve been expressing themselves for a week. The show represented normalcy. People were like, “We miss the world the way it was.” I mean, nobody was naive. It wasn’t like people were going, “Okay, it’s time to forget.” It was about, “We’ll always remember what happened on 9/11, but we also want to remember what happened on 9/10.”

I remember worrying, Maybe comedy won’t be important for a long time, or maybe it never was? So it was very comforting and reassuring to feel like audiences were basically tipping their hat to the idea that, “No, comedy is important too. Everything is important. Everything that used to be is still important.”

“There will never be anything funny about 9/11.”

Bob Saget

About two or three weeks right after 9/11, I went to New York because I had a press tour for a TV show I was doing that was premiering October 5, 2001. I think I went up at the Comedy Cellar and talked about it a bit — sarcastically and backhandedly plugging a sitcom — and how meaningless everything felt. Especially show business. And yet, I also felt that it was my job to make people laugh when I could, as soon as it felt they wanted it and needed it.

I had not one joke about 9/11. When I did stand-up, it was to distract with my silly jokes, and if they were irreverent, it was only in the way of talking about things that were unrelated to that event, in my PG-19 style of comedy. There will never be anything funny about 9/11. I have never done a joke about it. The mere mention of it does for me what it does for most people: It makes us hurt as deeply as possible for those people that perished and for all of those who lost their loved ones.

“I just wanted to give a respite or levity. Our hearts were broken.”

Sheryl Underwood

When September 11 happened, I was determined to get back onstage doing comedy because of my love for this country — my love for New York and being a prior Military Air Force Reserve. I wanted to show that you weren’t going to beat America.

Me and Mike Washington, who was my opening act, were at the Cleveland Improv, and I was doing some very urban, what we call “hood patriotic” material. I was telling a joke about the plane, United Flight 93, and what would have happened if there had been some real brothers or sisters on that plane — that the plane wouldn’t have crashed; we would’ve landed it. At the end of the show, a white couple walks up to us, crying. Me and Mike think we have offended them. So I start to apologize and go, “I didn’t mean to hurt your feelings.” And the guy says he was in the tower trying to guide in United Flight 93, and that he had never laughed so hard.

Then, together, it was a communal moment, because here you have a mixed crowd, different people, but we were all Americans; you’re talking about the hood of Cleveland with white people, and everybody is laughing and cheering and like, “We’re pro-America right now.” Just because I’m pro-America don’t mean I’m anti-anybody else. But this time we wanted to show that we back our president, we back our troops. I just wanted to give a respite or levity. Our hearts were broken. But just to see that man and his wife, and they came toward us and said who they were, was one of the proudest moments of my career.

“I said ‘Fuck it’ to any ‘too soon’ reactions and made the choice that it is never too soon to ask the tough questions.”

Lizz Winstead

I got onstage two weeks later, at a benefit in Minneapolis. I was full of rage and did a freeform set from my gut, talking about my reactions to 9/11, and mostly about the naive reactions from Americans who had no idea how our nation’s foreign policy has done harm around the world. I explored the common musings, “Why do they hate us?” and “They hate our freedom?”, and answered it with a set rooted in the idea that I can’t speak for them, but I know why I hate us.

Women, people of color, and queer folks in the crowd understood, because we all had been living in an America that had never offered to us the benefits straight white men enjoyed. I made a choice to take on blind patriotism, and it resonated with those in the audience who felt conflicted and angry our nation was attacked, while often being left out from, and often harmed by, its policies. I wanted those people to feel they were not alone with their complicated feelings, and that it was okay to have them.

I said “Fuck it” to any “too soon” reactions and made the choice that it is never too soon to ask the tough questions.

“Yes, it’s terrorism. Yes, it’s tragic. But, for a comedian, let’s talk this through.”

Roy Wood Jr.

On 9/11, I was working in Jackson, Mississippi. I’d graduated college that April and I was living back in Birmingham, and I was just a road comic doing MC work where I could. The morning of 9/11, I was supposed to go to Louisville, Kentucky, to do my audition set at the Comedy Caravan, a club in Louisville that made comedians audition in person on Tuesday nights for the right to feature for that club and for other clubs.

9/11 happened, and I get an email from the club around noon. They canceled the show. The next night, I have a show in Jackson at a bar. I had called the bar and they’re like, “Yeah, we’re open.” So, as far as I’m concerned, I have a job to do. Yes, it’s terrorism. Yes, it’s tragic. But, for a comedian, let’s talk this through; let’s figure out a way to process it. But I wasn’t really thinking about it like that. I’d only been doing comedy for three years. I needed stage time. I can’t afford to be canceling gigs. 9/11 or not, I have to go get onstage.

I was not sharp enough, at the time, to do any material about what was happening. But the thing I’ll never forget is that the bar had the TVs on and they had it on ESPN, but at that point, ESPN was still carrying the ABC News feed, and they were still showing the building smoldering and people covered in ash. So, half the show, it’s just people looking at highlights of 9/11 from the bar while comedians are onstage trying to be the escape.

For the most part, I bombed. I don’t really remember how I did. I don’t remember anyone laughing, but I don’t remember anybody really being disassociated. I mean, shit, I was looking at the bar while I was onstage, because that helped to inform me of when I could hurry up and do another joke real quick: Oh, they’re in a commercial break. Let me hurry up and maybe I can say something real fast. That was my 9/11.

“Most comics took the side of ‘America’s got to get those terrorists.’”

Nick Youssef

When you’re a year into comedy, you’re still doing open mics, and there was no real community; it wasn’t very tight-knit because people are very transient that first year. I remember calling another comic or two going, “Did you see what’s on the news? Should we get together and talk? What’s going to happen with comedy this next week or two?” No one knew what to say or do. So that morning and that day was just really nerve-racking in terms of, Can I go outside? Can I go anywhere? What am I going to say if people start asking stuff?

I remember a lot of comments out of the gate took a very patriotic stand — not in depth, but it was very like, “Let’s get them!”, that kind of thing. There were a lot of “If we don’t do blank, the terrorists win” jokes; those were happening immediately. Most comics took the side of “America’s got to get those terrorists,” and then just a wave of jokes about how bad Middle Eastern people look and smell, and the food, and “Maybe if they didn’t beat their women, they wouldn’t want to blow things up,” and all the stuff that’s super hacky now about the Arab world. There were endless amounts of jokes about that kind of stuff, and people loved it. They ate it up.

“My white American friends were super scared for me, but I wasn’t nervous at all.”

Maysoon Zayid

I started doing stand-up comedy nine months before 9/11 and was doing five to seven spots a week all over New York City when the terrorists attacked. My first set back was on September 21, 2001 at Bananas Comedy Club in Hackensack, New Jersey, which was booked prior to the tragedy. I am an entertainer, and the show must go on. I am also an Arab Muslim Jersey girl who was suddenly being painted as an un-American enemy of the shore, so I thought it was super important to get back onstage and tell tampon jokes. I never considered canceling it.

My white American friends were super scared for me, but I wasn’t nervous at all. Getting back onstage was one of the greatest moments of my life. Seeing the city in ruins across the Hudson broke my heart. I was so happy to be back doing what I loved.

I talked about 9/11 right off the bat. I had no choice. I did a joke based in reality about how my best friend called me and asked me, “What do you know?” — like did I have a heads-up? But I didn’t try to find a joke in the tragedy. We all lost people that day. It is still too soon to laugh about. But everything surrounding it is fair game. Especially the bigotry and hate my community was targeted with — that is comedy gold. And the audience seemed relieved. This was Jersey; we witnessed it firsthand. I remember noticing people really happy to see each other. I had a great set. They laughed wildly.