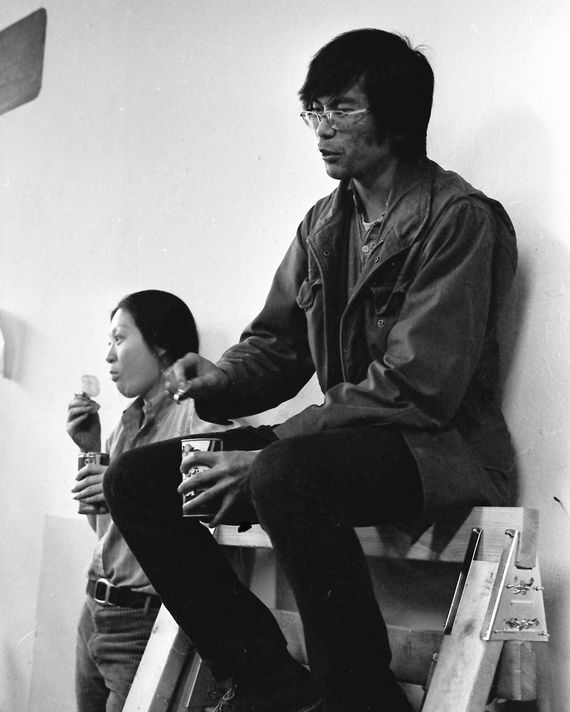

Anyone who knew Corky Lee will tell you that he seemed to know everyone and be everywhere. Whether he was at a Dragon Boat Festival in Queens or among a throng of protesters in Chinatown, the 73-year-old photographer and activist could be found snapping pictures and chatting eagerly with the other participants. Once he caught wind of your interests, he would rattle off a list of everyone you needed to speak to and offer to share their contacts, nonchalantly handing you a business card that designated him “the Undisputed Unofficial Asian American Photographer Laureate.” He might also hand you a flyer promoting an Asian American event — often one of his own, such as the Sunday film series he ran out of the First Baptist Church on Pell Street. It was said that Corky Lee had the best Rolodex in town.

Over more than four decades of photography, Lee also created a definitive body of work capturing Asian American life — from the intimate moments of a restaurant worker’s off hours to the grandeur of collective movement-building. He made his life a ceaseless act of creative intervention in a history shaped by erasure. Before his death on January 27 of complications from COVID-19, the self-proclaimed “ABC from NYC” (ABC stands for American-born Chinese) spoke of his camera as a sword that he used to pursue “photographic justice” by documenting the overlooked role that Asian Americans played across the U.S. His pictures — joyous, banal, specific, upsetting, uplifting — were close studies and celebrations of the complexities of community.

Lee lived in Queens, the same borough where he was born in 1947 to Toisanese immigrant parents, one of five children. His mother was a seamstress, his father an undocumented laundryman — a “paper son” who served in World War II. At the time, Queens did not have the thriving Chinese community it does today. (That wouldn’t change until 1965, when the U.S. removed quotas on non-European immigrants.) Jean Leung, an old friend of Lee’s and fellow Chinese laundry kid, says that when they were growing up, the Chinese community in New York was “tiny, tiny, tiny”; living far from Chinatown as the only Asian Americans around, they felt like “super-minorities.” Lee would later attribute his life’s path to a black-and-white photo he saw in junior high depicting the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869: Workers crowd around a Central Pacific train and a Union Pacific train, whose meeting in Utah symbolized the unification of the East and West Coasts. The photo didn’t include a single one of the Chinese workers whose labor had been so crucial to the railroad’s construction. Lee’s dream became to restage that photo, documenting the momentous contribution of Chinese workers who never got their due.

Herb Tam, curator and director of exhibitions at the Museum of Chinese in America, met Lee at a protest in support of Ai Weiwei in 2011, shortly after he got the job at MOCA. “Corky comes up to me and says, ‘Congrats on the MOCA job! I have a question for you: What does the word Locke mean to you?’” says Tam. “I knew he was testing me. I said, ‘Gary Locke? The governor?’ And he’s like, ‘Yeah, I thought so, but no. Locke has a bigger significance in Chinese American history: Locke, California.’” Lee was referring to a town significant to the history of Chinese railroad workers. “It was his way of making you prove your rigor, your total investment in what you were involved in, probably measured against his passion.”

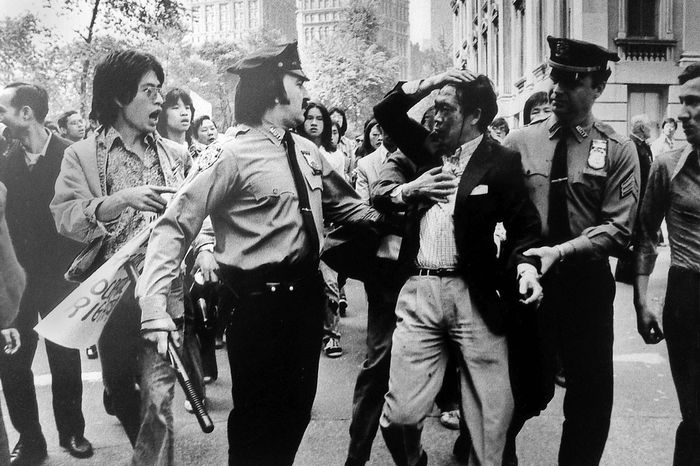

Lee was a self-taught photographer. One of the earliest pictures he sold was an image of a bloodied Chinese American man named Peter Yew, who was beaten by police after trying to intervene in their assault on a Chinese teenager. It ended up on the front page of the New York Post in 1975, and 2,500 Chinatown residents marched on City Hall in protest of police brutality. Lee would show up at protests against the Vietnam War or the construction of a jail, or join picket lines with Chinatown workers protesting their exploitative employers. Rallying fellow artists and activists he met, he helped found influential community groups and collectives, including Basement Workshop.

The journalist Eveline Chao has written about the role that Lee played in documenting such groups’ activities at a fractious time in the late ’60s and early ’70s, when the Chinese diaspora split along ideological lines. Lee was on the left: In 1971, inspired by the Black Panthers and the Young Lords, Lee helped organize a health fair along Mott Street where locals could get free testing for lead poisoning, diabetes, tuberculosis, and other conditions. The turnout was so large that the group moved to create a more permanent location: a forerunner of the Chinatown Health Clinic.

In the early 1980s, Lee got a day job at Expedi Printing, a community-newspaper printer. The company informally shared space with several Asian American groups, including the Asian American Arts Alliance, which Lee helped found in 1983, regularly printing pamphlets for student protests and newsletters for local advocacy and artist groups. The job — which he kept for decades — was amenable to Lee’s activist lifestyle, allowing him to dash out at a moment’s notice to photograph the goings-on.

For Lee, showing up to any event went hand in hand with documenting it. His pictures are formally and narratively striking, tracing a whole tapestry of relations woven of smaller details: An image of the Jing Fong restaurant workers’ strike in 1995 depicts a crowd of protesters in the background as a policeman glares at a worker burdened by boxes in the fore. The interlocked arms of young men at a march mirror the swooping billows of a banner with Chinese characters. The bold lines of a cityscape clash with angled rectangles of protest placards. A young Asian American woman strikes a Lady Liberty pose, holding a newspaper in place of a tablet, while above her strong stance an official street sign reads, “NO STANDING ANY TIME.” Text adds layers of commentary and humor in the form of street signs, restaurant signs, protest signs, police barricades, advertisements, and logos — and sometimes functions as captions, turning passing moments into historical monuments. We see events unfolding in all of their unpredictable glory through the determined forward movement of an individual or a group in action. Lee’s subjects were doers.

Although Lee seemed to be friends with everyone, he was unapologetic about his opinions. He never quite forgave MOCA for becoming more institutional — he thought it had lost something of its original mission to honor the Chinatown working class — but he was still sure to show up at every event. Photographer Cindy Trinh, who considers Lee a mentor, can’t help laughing as she remembers when they first met, at an artist talk at MOCA: “I was talking about my photography, and he immediately started to critique my work! But when Chinese elders offer criticism, it’s a sign of love and care.” One time, he came to one of Trinh’s exhibitions with a cane after a recent hip injury. When Trinh insisted he go home to rest, he insisted on staying to help. “He would never compromise himself and his work for anything, not for fame or money, none of that,” says Trinh. “That’s what I learned from him: to keep doing the work that you care about.”

In 2014, after years of research that he funded himself, Lee gathered a group of the American-born descendants of Chinese railroad laborers at the exact spot in Promontory Summit, Utah, where white workers had been photographed in 1869. Lee photographed the group, posed joyously, in period garb, with arms outstretched between the two trains, the task of connecting East and West here taking on a double meaning. “The transcontinental-railroad project was him trying to heal a big wound,” says Tam. “The end goal was the photo, but what it took to bring everyone there was deeply important to it. That’s what will continue.” That gathering turned into a yearly commemorative event.

Lee did a residency at the gallery space in Pearl River Mart in 2016, mounting an exhibition of his photographs, “Chinese America on My Mind.” Pearl River president Joanne Kwong says that “for every picture on the wall, he had a story. He remembered dates, addresses, who was there, what the weather was. He knew everything.” Working with Lee was a lesson in art as well as organizing; he taught Kwong not only how to hang an artwork but also the importance of having friends around to help mount photos and schlep materials. He was the one who reminded organizers to buy toilet paper before a whiskey-fueled all-nighter while setting up for an event and to block out time on the schedule for dim sum. He understood the importance of both sharing revolutionary histories and making sure there was time to talk about them over dumplings.

Someone needs to care about those oft-overlooked yet vital details, and this care lies at the core of Lee’s twin practices of photography and activism. “I’m one of so many people like me who came into his orbit, young people interested in Asian American issues and Asian American life, who would show up at things, not really know anyone, be standing off to the side,” says Chao. “He would be the first person to come over and notice you and say hello, then take you around and introduce you to everyone there. That’s who he was … He was Chinatown to me.”

Kwong remembers the last time she saw Lee, when volunteers gathered to weatherproof some 150 colored paper lanterns for a festive installation on Mott Street in December. Following the long evening of hard work and revelry, Lee returned to drop off a few mementos for Kwong, all lovingly packed in padded ziplock bags: printouts of photos scrawled with his signature and a USB with a little note that read, “Corky would like his flash drive back.”

The writers are the founders of Canal Street Research Association.