Eleven nominations: It’s too many.”

Daniel Kwan is describing a conversation he had with his mother, June Kwan, on the day the Oscar nods were announced. He and Daniel Scheinert, professionally known as Daniels, are the directors of Everything Everywhere All at Once, the 2022 sci-fi kung fu family comedy-drama that is the highest-grossing film ever released by its studio, A24. It steadily gained viewers and fans over the spring and summer of 2022, a slow-rolling word-of-mouth indie theatrical phenomenon in an era when such things are supposed to have gone extinct. Its number of nominations, including Best Picture, is more than any other film this year, making it one of the most unlikely awards-season juggernauts in recent memory. It turned its star Michelle Yeoh, a legend of Hong Kong cinema, into a major contender. It revived the career of her co-star Ke Huy Quan (also a nominee), who was an iconic ’80s child star but had drifted away from acting after realizing there were almost no roles available for Asian leading men in Hollywood. It also garnered a nomination for Jamie Lee Curtis — incredibly, her first.

Kwan’s mother happens to be right here. The directors are in New York amid a press tour for their whirlwind Oscars season, and they’re making a pit stop at Spicy Moon, the vegan Szechuan restaurant June owns in the East Village, where she’s plying us with food. On nomination day, June was on the phone with her son. “My mom was very proud but confused by the nominations. She was like, ‘I know people like the film, but can you explain why people love it?’” To be fair, it’s a difficult film to explain, bursting with ideas and images and often digressing in bizarre directions. It centers on Evelyn Wang (Yeoh), a middle-aged Chinese American laundromat owner who, in the middle of a busy day that involves both a Lunar New Year celebration and an IRS appointment, discovers she may be the most powerful being in the metaverse and the only one strong enough to defeat a sinister, nihilistic force named Jobu Tupaki (who happens to be an alternate-universe version of her daughter) that is threatening to consume all of creation. To harness her powers, Evelyn must jump between different universes and iterations of herself.

“For my generation and my language skill, I can’t just open my senses and feel it,” June says. “I have to think, What is this? What is that? I can’t catch up with it. The audience is a different generation, and they perceive it very different from me.”

“I started to explain what our intentions were,” her son says. “She said, ‘Maybe one day a film writer will write something that will make me understand why people love it so much.’”

All eyes turn to me. I make an awkward, verbose stab at it, explaining how the film artfully approximates the texture and pace of life in this day and age when one can be juggling multiple personalities and life threads at once — a world where you may be answering an important email from your boss while arguing with a dozen bozos on Twitter, trying to file your taxes, and dealing with assorted family drama. But of course it’s not just that. It’s also the way the film, through its multiverse story, plays with the idea of might-have-beens, of decisions made in the past that changed the trajectory of our lives. That particular thread perhaps connects to the immigrant experience, to those of us who spend a lot of time pondering how we might have turned out had we not left our home countries behind and often wonder how that me-who-never-left is doing — a kind of multiverse of the mind.

Those who get it really get it. Daniels’ fans don’t just adore them; they feel like they know these two men. “Someone just came up to us and gave us groceries from Chinatown,” says Kwan, referring to a screening they attended the previous night. “He had a dragon pinned to his jacket, and he said, ‘Tomorrow night, I’m bringing three dragons for you.’” At a screening in London, they met a young fan who had flown all the way from Turkey to give them a personal letter presented like a tax form. A lot of people bring their parents, moved by the film’s portrait of generational conflict and reconciliation. The directors recall one young woman who brought her mother and then just started crying, unable to talk. “We’re like these five-minute therapists sometimes,” Scheinert says. At a Q&A after their world premiere at South by Southwest, the directors were surprised to find almost all the audience questions directed at them despite the fact that they were up there with their stars. The first one, Scheinert recalls, was about generational trauma. Then came one about mental illness. Afterward, a friend observed they could probably start a cult if they wanted to.

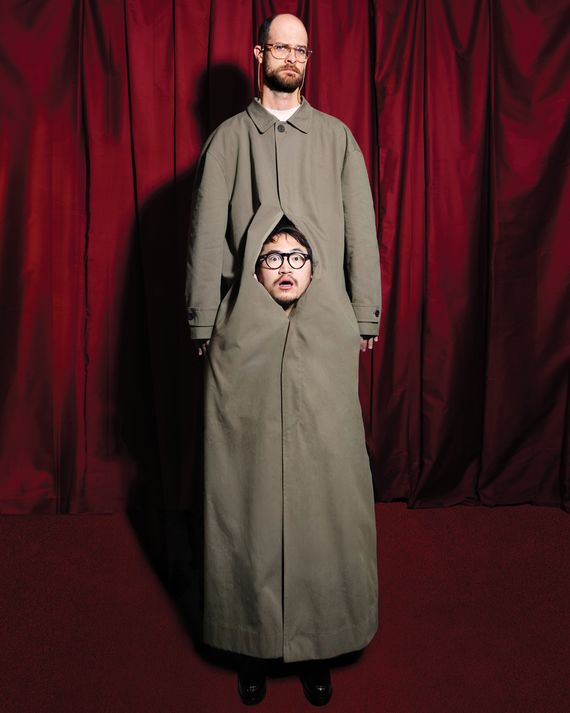

Scheinert and Kwan met as students at Emerson College. Scheinert, who had grown up in Alabama and become immersed in musical theater and improv comedy, was the confident talker. “I sometimes participate too much and come off like one of those assholes who suck all the air out,” he says. At an introductory 3-D animation class, the professor asked the students what kind of movies they wanted to make. Scheinert announced, “I want to make dramas that make you laugh and comedies that make you cry. My name is Daniel!” Kwan, who had transferred after a depressing year at the University of Connecticut (where he flirted with doing something responsible, like accounting), was the opposite: the quiet kid in the back of the class who rarely spoke up and had zero confidence. He said he didn’t know what kinds of movies he wanted to make.

Kwan and Scheinert individually made their own films for Campus Movie Fest, a nationwide collegiate short-film competition. Scheinert’s, produced with his comedy troupe, was an elaborate action movie called Danger: High Voltage, filled with car chases, gunfights, and explosions. He and his friends used their own voices to do the sound effects and music; for a scene involving a wood chipper, they just held up a handwritten sign that read WOOD CHIPPER. Kwan’s effort, Balance, was an animated short about a star falling through a city, bouncing from place to place, while two kids have “an eye-rolly, philosophical conversation” about whether everything in life is connected or totally meaningless. Scheinert was immediately taken: “It was gorgeous. Like, What? One kid made this?”

It’s not hard to see in these early movies the directors’ sensibilities in embryonic form — the collision of storytelling ambition and low-tech production values on one side and the sensitive but playful philosophical rumination on the other. Not to mention a heady dose of deranged surrealism. Scheinert’s short ends with the rule-breaking cop hero discovering he has been dead all along because a baby he shot in the opening scene was actually himself. The end.

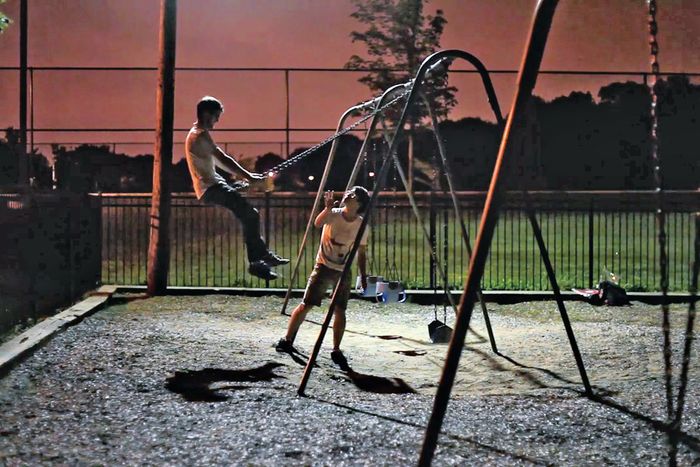

The two grew close, united by a shared love of Stephen Chow movies, Miranda July short stories, Kurt Vonnegut novels, and Wes Anderson’s The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou. Their first real collaboration came in 2009, when they were counselors at a New York Film Academy summer camp in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “We got jealous of the kids,” says Kwan. He had just gotten a Canon 5D Mark II camera — a piece of technology that would become instrumental to the digital-filmmaking revolution — and one night, walking back to his apartment at 2 a.m., the two decided to test it out in a nearby playground that had some cool lighting. The result was a 55-second short called Swingers, in which an absurd playground-swing malfunction leads to Kwan and Scheinert colliding and getting their facial features mixed up.

The short wound up being a “Staff Pick” on Vimeo. “The internet approved, so we were like, ‘I guess we should try again,’” says Kwan. Their next effort, Tides of the Heart — a 51-second short in which Scheinert gives Kwan an inspiring speech that leads to an enormous boat bursting out of Kwan’s chest — was also an online hit. After college, Scheinert moved to L.A. and talked his way into a gig shooting a music video for free for the song “Underwear,” by FM Belfast. He convinced Kwan to join him. “I made him help more and more until he was starring in it, co-directing it, editing it,” Scheinert says. The video was well received, and they were offered $12,000 to make the next one. “We never thought we’d become these music-video directors,” Scheinert says. “We were like, Oh, I guess we’ll do another one. Oh, I guess we’re a duo. Oh, I guess we’re a duo that does music videos.”

When they pitched their music videos, Scheinert and Kwan would sit you down, press PLAY on the song, and exuberantly narrate their ideas. “They hopped in and out like the Beastie Boys,” says Larkin Seiple, the Daniels’ cinematographer, who has known them since college. The “Daniels pitch” was never slick or high concept or normal in really any way, but the whole thing was powered by their cheerful, goofy energy. They would work a silly, strange idea until it led to some moment of catharsis or revelation. “It would be something stupidly absurd that makes you feel something,” Seiple says.

The videos bear this out. In Chromeo’s “When the Night Falls,” the band’s music instantly turns women pregnant, and the musicians are chased by a rampaging army of pregnant women who ultimately corner them and make them pregnant (the whole thing is about owning up to your responsibilities as a parent). In their best-known video, DJ Snake and Lil Jon’s “Turn Down for What,” a furiously twerking Kwan blasts his way through the floors of an apartment building as an epidemic of hypereroticized dancing breaks out all around him with bouncing boobs smashing tables and spiraling erections breaking jars (that one is poking fun at male hypersexuality). “Turn Down for What” caught fire on YouTube and currently has 1.1 billion views. Virality helped the Daniels make a name for themselves. At the time they conceived of and pitched that video, they were at the Sundance Labs, where they had been accepted to work on the script of their first feature film, Swiss Army Man — which starts with Paul Dano riding Daniel Radcliffe’s farting corpse across the ocean (by the end, it becomes a tender story of friendship, loyalty, and ego death). When the video became a massive success, that and the Sundance imprimatur helped them get Swiss Army Man off the ground. “The validation coming from the algorithms has shaped our careers in a way we would never have done on our own,” Kwan says. And the influence goes both ways. “A lot of the stuff people see as out-there feels normal to us because so much of what we ingest is the craziest animes or what the internet is doing on Tumblr and YouTube,” Kwan says. “So much of our inspiration is outside the language of cinema.”

They started building a collective of collaborators they work with on all of their projects. “So much of our job is curation, finding the right people to become extensions of you,” Kwan says. Seiple came onboard after seeing the FM Belfast video. Their production designer, Jason Kisvarday, joined soon after. Producer Jonathan Wang sought them out at the 2011 LA Film Festival and has produced almost everything they’ve made since. Today, many of them live and work within walking distance of one another in L.A., so the work is sometimes indistinguishable from a hangout. “The Daniels are happy to be in this creative petri dish they created,” observes Jamie Lee Curtis. “They recognize how collaborative the art form is. It’s unlike anything I’ve ever been a part of.”

For EEAAO, the directors sat some of their friends and collaborators down and pitched the whole movie. The idea wasn’t just to sell them on the idea but to see what was and wasn’t working. “Very early on, we were like, ‘In this one, we’re going to make them think they’re watching a normal movie, and it’s going to get weirder and weirder until all purpose and meaning breaks down until the end,” explains Scheinert. By the time they were done, their editor, Paul Rogers, was on the verge of tears. “I thought it would piss more people off,” Scheinert recalls.

Eventually, it did: EEAAO wound up being review-bombed on IMDb after the Oscar nominations were announced. (“Overhyped” and “overrated” were common descriptions.) But the pair are honestly surprised it didn’t annoy more people. Scheinert has a theory about why: “Once an audience loves a character, they’ll go through so much. And it’s not just the character. It’s the actress.” Seeing Yeoh, one of the shining lights of international cinema, demonstrate her range can win over even the most skeptical viewer. Both she and Quan, a familiar face returning to movie screens after decades, add a certain metatextual lift to the multiverse story.

And then there’s Racacoonie. In one of the multiverses of EEAAO, Evelyn is a clumsy, struggling chef at a Benihana-style Japanese steakhouse, and her star co-worker turns out to be hiding a talented raccoon under his hat to help guide him through his mealtime performance. This is partly a joke on the fact that Evelyn, in the film’s present universe, can’t remember the title of the Pixar movie Ratatouille and calls it Racacoonie. (It’s inspired, Jonathan Wang says, by how his own father always butchered movie titles: “Good Will Hunting he called Outside Good People Shooting.”) The raccoon itself is a phony bundle of matted fur and jaunty limbs. Scheinert and Kwan told their props department to “make it look like someone went and got a bad taxidermy.’” This handmade quality is one of the Daniels’ primary charms. It tempers their philosophical ambitions and keeps their films from feeling self-important. It also speaks to a sensibility that embraces awkwardness at a time when movies maybe look a little too polished. “To come back to the limitations of physical filmmaking can be refreshing,” Kwan says. “I’m very proud of the fact that there’s a jankiness to it. I think that’s what people are responding to.”

June remembers the days when her son was miserable at UConn. “Walking through the campus, to the store, to class, I can feel you were like a zombie,” she says to him. She was the one who urged him to go to film school. “You can’t do anything,” she recalls telling him. “The only thing you can do is try film.”

“My mom was just being real,” Kwan tells me. “She could tell I can’t do anything.”

A lot of it, it turns out, was undiagnosed ADHD. As a child, Kwan never said no to any assignment or project, June says, but he would sit at his desk for hours and never make any progress. “Just no result, like a dummy,” June says. “It’s executive dysfunction, Mom,” Kwan replies. “People with ADHD have trouble with motivation because we don’t have normal dopamine activation.” Kwan didn’t discover he had it until years later while at an impasse in the edit of Swiss Army Man. The two partners had found themselves at odds over how to handle the first act. They had never done a feature before, and after stress-testing the film, Kwan was dissatisfied with the opening. “Scheinert tends to protect the ideas, and I’m the one who is always wanting to improve or expand the ideas,” Kwan says. Upset, Scheinert walked out of the edit room. “Sometimes, when he’s being hard on the movie or hard on himself, it feels like he’s not noticing he’s also being mean to a movie I co-wrote and being mean to me,” Scheinert says with a chuckle. “Another way of putting it is my ego starts getting hurt.”

The narrative problem was eventually fixed after Kwan and the editor, Matthew Hannam, got high and came up with a new scene. Around the same time, they had begun conceiving of EEAAO and were toying with making it about someone who had such severe ADHD they could tap into another universe. Researching the character, Kwan realized he shared the condition. When he and Scheinert met over a drink to iron out their differences, he told his friend this was probably why he felt like he’d become such a bad collaborator. “It was like, Oh, now we have a word for it,” Scheinert says. Many people with ADHD can hyperfixate when they find something they’re interested in. “To be able to sit down and work on one thing until it’s incredible?” Scheinert says. “I would say that’s Dan’s superpower.”

Curtis describes Scheinert on set as “the actor whisperer,” while Kwan is more “the technical, visual person.” Because of his improv background, Scheinert has a very “yes, and” sensibility, which often prompts Kwan to seriously consider some of the strange ideas they have. (This is, they tell me, how Swiss Army Man started. Kwan threw out a silly thought about riding a farting corpse, and Scheinert “wouldn’t drop it.”) Kwan can come up with a million ideas and then never think of them again, but he also likes to explore them in depth before he abandons them. Scheinert likes to keep things moving. He recalls running around the EEAAO set repeatedly reassuring his cast and crew that they weren’t making an Oscar movie. “We genuinely told people this movie was quantity over quality,” he explains. “To take them out of the mind-set of a lot of filmmaking, of movie directors who are going to scream if they don’t have four options for a sofa in a scene. This isn’t that kind of movie. If you get us a sofa, we’ll roll with it, man.”

The question now is what happens to a partnership that has up until this point succeeded through its casual, collective, no-pressure nature. Last week, the Daniels won the top Directors Guild of America award, a historically reliable predictor of the Best Director Oscar winner. “I’m still the kid in the back of the class,” Kwan says. “This Oscars stuff is horrifying to me.” They’re also keenly aware that they may never again find themselves in a position like this with the ability to be as ambitious as they want.

The directors always have a number of ideas they’re mulling; lately, they’ve been reading and listening to philosophers, futurists, and activists on the subject of the “metacrisis,” which Kwan describes as “the main funnel that causes all the other crises.” In other words, many thinkers believe everything from climate change to political extremism to economic turbulence is part of a more existential crisis around how people view themselves and their world. “As storytellers, so much of our job is to make the illegible legible,” Kwan says. “We’re taking all the information and noise of the world that’s constantly flooded into our receptors and trying to create narratives that sum it all up. That’s why we tried to make EEAAO, because we were so overwhelmed.” They can be critical of their own ideas, and they struggle with the notion of preaching to the choir. “In some ways, one of the problems with EEAAO is we tried too hard to compress it all down to something.”

That tension might not be such a bad thing. The Daniels may conceive on a complex conceptual level, but they execute through instinct and taste — those ineffable qualities that often distinguish the work of artists from that of mere dreamers. “We bring a naïveté to everything we do,” Kwan says. “We don’t know better, and that’s why we do it.”