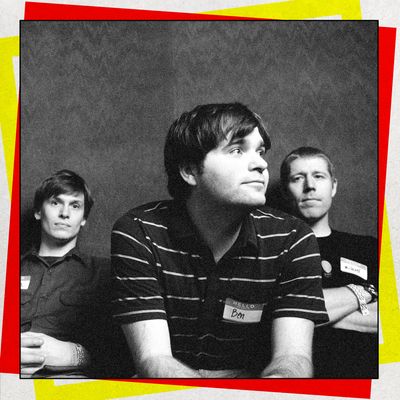

Let’s get this out of the way: The Photo Album is far from Ben Gibbard’s favorite Death Cab for Cutie album. The band’s lead singer and songwriter isn’t shy about admitting that, even though he’s given it a deluxe reissue for the album’s 20th anniversary. “It’s kind of a cheesy analogy, but records are like my kids. I don’t have any children, so they’re kind of my contribution to the world,” Gibbard says. “You love them all, but you can see how one’s going to struggle to keep a job. The other one’s going to maybe go off and become a doctor, right? You can see them very clearly, certainly as you get older.”

The way Gibbard tells it, The Photo Album, the band’s third full-length, came at a stressful point. Death Cab for Cutie had been touring heavily to make money and was facing the prospect of following up their second album, 2000’s We Have the Facts and We’re Voting Yes, and follow-up project from that same year, The Forbidden Love EP, both of which took the band to a new level of popularity. “Our profile just shot up in that year, year and a half,” Gibbard says. “In economies of scale, it’s not that big, but going from selling 10,000 records to selling 50,000 records seemed like a massive jump at the time.” He struggled to find time to write enough songs for a new album that could keep the band touring; reflecting on the album in 2018, Gibbard told Noisey that many of the songs “are really underbaked.”

Yet The Photo Album is also the album that made Death Cab for Cutie what the band is today. As the band’s arrangements got bigger and more sweeping, Gibbard’s poignant lyrical vignettes became tighter and more refined. It was a winning formula: “If it’s true that music of this nature doesn’t get anymore heartfelt, it also rarely gets more infectious,” a Billboard review at the time declared. And it only solidified the band’s place in the emo canon, arriving as the genre’s second wave was spreading across the Midwest. Most notoriously, though, The Photo Album put Death Cab on the path to be one of the most commercially successful indie-rock bands of the 20 years to come after The O.C. used the song “A Movie Script Ending” in a memorable scene during the main four’s road trip to Tijuana, of course on Seth’s playlist. (Summer’s review: “It’s like one guitar and a whole lot of complaining!”) That song became Death Cab’s first to crack the charts, putting the band on a path to future No. 1 albums and licenses.

To celebrate the album’s 20th anniversary earlier in October, Death Cab released a 35-track deluxe of the album. It features demo, acoustic, and live versions of the original ten songs along with the three off the following Stability EP, which were written around the same time. Gibbard also recently spent some time reflecting on the album and its legacy with Vulture. “It’s a trip that it’s been 20 years, of course,” he says. “Time just flies.”

Song that changed the most from its demo

There are a number of songs on the record, maybe three or four, that when I brought them in, they were really minimal. They had just a verse and a chorus, maybe a double chorus for the end, but fairly minimal arrangements. When I turned in the demo for “Coney Island,” it had like a Neil Young, After the Gold Rush kind of stomp to it, very simple chords. As we were starting to dive into that song in the studio, doing the kind of folk-rock stomp thing just didn’t seem appropriate for the band at the time. It wouldn’t seem appropriate now either. It seemed like an opportunity for Chris and the rest of the guys to really get creative with this very simple structure.

I wouldn’t say that it’s one of my all-time favorites or anything like that. It certainly was indicative of the process and the record — like, Okay, let’s take the song that is in its infancy, very straightforward, and try to make something a little bit more pastoral and Death Cab out of it. I think that song has the most contributions from everybody as far as the sonic palette and the arrangements go.

Favorite Photo Album song to play live

Songs like “A Movie Script Ending” and “Why You’d Want to Live Here” and “We Laugh Indoors,” we played those songs on maybe three or four tours before we went into the studio. If you wanted to preserve the newness or the workshop element of the song you were playing live, it was very easy to do that in 2000, 2001, because YouTube didn’t exist. It was nice to hear some people come up after shows and be like, “What was that song you played, like, fourth? You said it’s a new song,” and be like, “Oh, that’s called ‘A Movie Script Ending.’” “Oh my God! I love that one. Is that going to be on the next record?” It was a nice point of conversation with fans and not necessarily an opportunity for people to capture something exclusive.

To this day, my favorite is still “A Movie Script Ending.” We’re in this very fortunate position where we’ve got a lot of songs that we kind of “need” to play every night. So playing songs from the first three records, we have limited space in the set to do that. “A Movie Script” is one that we rotate in.

It’s one that, not only do people tend to recognize more, but also for me, it’s a very sentimental song. It was a song I wrote about Bellingham, Washington, after we moved to Seattle. Bellingham is where we started. I went to college up there, and it was a very idyllic, dare I say innocent time in all of our lives, both personally and creatively. This is an era before social media, where you could experiment, and you could fail, and you could make mistakes — both in your personal life, but also musically — and really develop who you are as a person and as an artist. I wanted to write kind of a torch song for Bellingham that referenced places there that people who live there or used to live there would get. It was a song just for us.

B side that could’ve made The Photo Album

There really isn’t. One of the things that was little bit harrowing about making The Photo Album is that it was very much, as the trope goes, the difficult third record. The short of it is that you have your whole life to write your first record. The second record is whatever’s left off the first record and then the five songs you wrote in the last six months. And then the third record, you’re starting from scratch. You have nothing to pull on from the first couple records. There’s a reason that’s a trope, right? It tends to be true almost all the time.

Going into making The Photo Album, I was finishing the last little bits of the ten songs that we had complete the week before we went in the studio. We had a plan to have the record out in the fall, and we had to have a record to be on tour. It was in this weird, liminal space where the band had become our job, but we weren’t really making much money from it. It was an incredibly stressful record to make because every song had to work. The ten songs we had bookmarked for the record all had to make the record.

We had a longer version of the original version of “Stability” that was called “Stable Song.” That version ended up on Plans two records later, but we really only had “Stable Song,” which, in its form on the Stability EP, came out to be this long, expansive thing that Chris made, which I still totally loved. Then this slowcore, really down song, “20th Century Towers,” and a Björk cover, “All Is Full of Love.” That was all we had. So when I think of The Photo Album, I don’t think of it having any proper B sides. Everything that we recorded for that record made the record because we didn’t really have any more material.

Photo Album song you wish you worked on more

I’ve always loved “Blacking Out the Friction” in its simplicity. It’s just very simple chords. My four-track demo of it was very down and very quiet — different from the demos that are on this reissue. It didn’t really need to say anything more. But it’s funny because I was really happy with how “Coney Island” turned out, too, but I think that there’s a similarity between “Blacking Out the Friction” and “Coney Island,” in the structure and the chords. They’re kind of 1A and 1B. It’s like, verse with two chords, chorus and then verse, and then a double chorus, and the songs are kind of over. If I could go back and do it over again, we probably would’ve done a little bit more work to delineate those two songs. “Coney Island” maybe could have used one little extra section, something else to happen narratively or whatever.

But, you know, hindsight’s 20/20. Those are songs that people don’t scream for all the time, but it’s funny how every song is somebody’s favorite song somewhere. There’s nothing about The Photo Album that I would go back and change — there’s nothing broken about it, but I feel that there are elements that are a little more minimal, or they lack a little bit of sophistication. I think it would’ve been nice to have more time to work on it, but it’s what it is. It’s a perfect snapshot of where we were at that time.

Favorite use of a Death Cab song in a movie or TV show

One of the things about our music that I think works, but sometimes is a very fine line to walk, is the way I write songs tends to be very specific. If I can be so bold, I tend to be kind of cinematic at times. I think what can be difficult about it is a director is trying to hit an emotional point with the music, but the music is also speaking about something very, very specific. So, you have this scenario in which the director is trying to overly nail what’s happening in the scene by having a song that’s almost exactly what it’s about. It would be like if somebody used “What Sarah Said” in a hospital scene. That’s pretty on the nose. Or you have situations where somebody’s using a song that is about something very different, but they’re trying to hit this emotional note, and that can be a little incongruent.

One of the things that I really like, even to this day, about the first usage in The O.C. is Seth and his friends are driving around, and Death Cab’s on the radio, and they reference something like, “Don’t diss Death Cab.” That was one of the first licenses we ever got for TV of any note. As we were not starving musicians, but certainly not thriving musicians, at that time, the money from a license on a major network was huge for us. They would help us pay our rent, and it was a big deal. So we tuned in to watch the show, expecting the song to be just playing in the background while somebody was doing something. Then to have this weird fourth wall broken, where you have these fictional characters using a band that exists currently as a point to bounce dialogue off of, was just a really surreal moment — to actually have it be referenced and almost be like a character in the show. From that point on, things continued to snowball, depending on your perspective, either for the better or for the worse. For us, I would definitely say for the better.

Most emo song

It’s interesting, I’ve always thought of us as being like, emo-adjacent. At the time that our band was first starting out, the things that we listened to and the bands that we admired, we didn’t … I had no knowledge, hand to God, no knowledge of the emo scene that was percolating in the Midwest and that people were throwing that term around with Promise Ring and Get Up Kids and Braid and whomever else. People would be like, “Do you like emo music?” I was like, “Oh, you mean like Afghan Whigs, like emotional?” He’s like, “No man, like the Get Up Kids and the Promise Ring.” I had not heard any of those bands.

I’m not dissing those bands at all, I was friends with a lot of those guys, but I think that particular scene seemed to me, even at that point, a kind of a dead end. We had been offered tours by some bands that will remain nameless that were very popular at the time in that genre. We always turned that stuff down because we felt like, that’s not how we want to be perceived. If people used the term emo to describe our music, we never got mad. We weren’t like, “Fuck you, we’re not an emo band.”

I get why we are emo-adjacent, or why people would consider us like an emo band, because of the kind of lyrics I write and how we present our songs. If you want to talk about what’s the most emotionally wrought song that we have, it would probably either be the song “Transatlanticism” or “What Sarah Said” from Plans.

I want to be abundantly clear, I have nothing but respect for all those bands that I mentioned. That is a scene that is certainly having a renaissance. It’s interesting to see some of the similar threads starting to flow through a lot of younger, specifically female, singer-songwriters that have grown up on a lot of this music and are taking a lot of that imagery and emotional weight and bringing it into music today. At the time, a lot of the music that got called emo was like, pop-punk songs about girls and sweaters. It wasn’t something that I listened to, and therefore we didn’t want to lean into the association.

Later song that reminds you of The Photo Album

I think a song like “Cath …” on Narrow Stairs could easily have been on Photo Album. The first three records are very guitar-forward. Chris and I would weave our parts together, almost a deconstructionist approach to arranging music. I did not want to play chords. I thought that just strumming a G chord and then strumming a C chord was the most boring thing in the world. I still do. As we progressed, there are new elements that started coming into the mix, as they were with a lot of people’s music. You see the emergence of the computer as an instrument and all the things you can do with that. I bought a piano for the first time, so I had a piano in my house, started writing on that. Our process for making music started to change, certainly through Transatlanticism and Plans. But Narrow Stairs was more of a throwback to the first three records than probably anything we’ve done since.

Biggest lesson from The Photo Album

It’s weird to say this because I feel like I’m knocking the record. I’m really not. There is this myth that we like to tell ourselves, that musicians make their best work when their backs are to the wall and when they’re fighting. We love these stories about how the Rolling Stones were having fistfights when they were making Exile on Main Street; these stories where it’s like, the Gallagher Brothers, they would kill each other, but then they made (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?; these stories that conflict creates great art. In my life and my career, that has been proven to be entirely false. The times at which our band was not getting along or fighting or we had our backs up against the wall of a deadline or whatever it was — that’s never been when we made our best work.

The Photo Album was a record that was made under intense pressure to follow up these two releases we had, We Have the Facts and Forbidden Love EP, where people were now really listening. At least, we felt that at that point. So, there was the pressure of that. There was the fact that we had been touring so much, and I didn’t have a lot of time to write songs. We weren’t getting along very well when we made that record. So for me, the biggest lesson that I learned in that process was that the trope that conflict creates the best art is entirely false. It makes a great story, but very rarely do you hear, specifically from a band, “Yeah, we had never hated each other more. I mean, that was the best record we ever made.” Like I said, Photo Album is not in my top-three Death Cab records. But I love it.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

More From This Series

- Hans Zimmer on His Most Unusual and Underrated Scores

- The Coolest and Craziest of TLC, According to Chilli

- Kim Deal on Her Coolest and Most Vulnerable Music