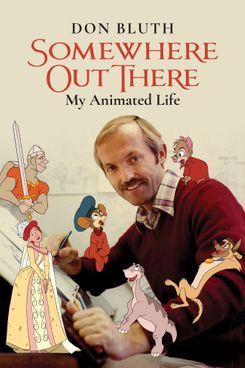

Despite being a master of the cartoon craft, Don Bluth still feels like an underdog, even now, just shy of 40 years since the release of his first film, The Secret of NIMH. His new memoir Somewhere Out There: My Animated Life, out July 19, is full of lessons he learned across his long career, charting his work at and, later, dramatic resignation from Walt Disney Animation Studios to how he struck out on his own to direct acclaimed titles like An American Tail, The Land Before Time, All Dogs Go to Heaven, and Anastasia. Alongside granular notes on “The Art of the Storyboard” and tips on how to effectively deploy cliffhangers, Bluth narrates a staccato career arc defined by highs and lows.

The lows weren’t easy. Bluth describes how the money was tight and the anxieties rampant. The excerpt below discusses how he had to learn how to negotiate the chaos of Hollywood in order to collaborate with Steven Spielberg — whose blockbuster E.T. completely crushed NIMH at the box office in 1982. After NIMH flopped, Bluth kept working, fielded late-night calls from another would-be Spielberg collaborator, and fought his own uncertainty before his next big break finally broke through. Ultimately, the persistence paid off; An American Tail became the highest-grossing non-Disney animated film upon its release in 1986. And Fievel Mousekwitz was far from the last scrappy, unforgettable hero Bluth would bring to life. This is the story of how he finally found “the perfect story.”

Excerpt from 'Somewhere Out There'

I. The Emperor of Hollywood

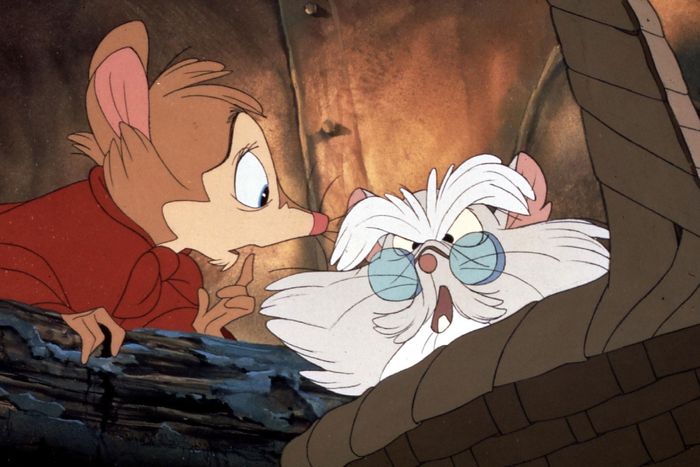

To know Jerry Goldsmith, the composer for The Secret of NIMH (among countless other films), is to love him, and not just for his musical accomplishments. He was a kind man, for one. For another, with his wispy white hair, whenever he stepped up to his podium and lifted his baton to conduct a studio orchestra, he looked like the reincarnation of the conductor Leopold Stokowski, conducting the orchestra for Fantasia.

One day, Gary Goldman pulled John Pomeroy and me aside and described a phone call he’d gotten from Jerry. Jerry had screened NIMH for a friend. “Jerry said his friend was bowled over. His friend said, and I quote, ‘I thought nobody did this kind of animation anymore.’ He wants to meet us.”

“Sure,” John replied. “Who’s his friend?”

Gary laughed. “You know that alien movie that destroyed NIMH at the box office?”

I interrupted with “Not Steven Spielberg?!”

Yes, that Steven Spielberg.

Spielberg’s people soon called our people to set up an appointment at our studio, which threw our people into a panic. You have to understand, this was like getting a visit from an emperor or a pope. Steven was the yardstick by which everything got measured. If he liked you, everyone liked you. We all frantically spruced the studio up, and on the day of his arrival, producers, crew, and staff wore their Sunday best. Dave Spafford had even gotten a haircut and put Waldo the rat in his cage.

I’d just shooed the crew away from clustering at the windows for the umpteenth time, saying, “His appointment isn’t for an hour,” when a jade-green Porsche roared into the parking lot and screeched to a halt. A man wearing baggy trousers, a Hawaiian shirt, and a beat-up baseball cap got out of the car. “He’s early,” I yelled, and everyone scattered to their desks to pretend to work — and to watch me welcome our box-office rival. Steven’s broad smile and enthusiastic handshake put me at ease, and when Gary joined us, compliments on our competing films flowed.

“And I thought that the golden age of animation was over,” Steven said as we led him into our conference room. “How much did NIMH cost?”

“Total was 9 million,” said Gary. “And entirely produced in the U.S.”

Steven’s eyes lit up. “I’ve always wanted to make an animated movie.”

Gary and I exchanged excited glances — was this for real? Just then, John ceremoniously entered the conference room with stacks of cels cradled in his arms. John’s great idea was to show Steven his collection of rare animation cels — to inspire him, John said. We reverently set out the stacks on the table before Steven. To Steven’s right, John placed a pair of white cotton gloves, which we always used to handle these valuable, delicate pieces.

Steven was as delighted as a boy in a candy store. He ignored the gloves and with his bare hands excitedly thumbed through the cels as if they were stacks of playing cards. “Snow White …” he gasped. “Pinocchio … Fantasia!” Finally, he reluctantly pulled away from those treasures and asked, “Say, are you interested in doing a movie together?”

I opened my mouth to say “Yes,” but my heart was racing so fast all I could muster was a croak.

Gary leaped in to save the day. “Yes, we’d love that!”

“Fantastic,” said Steven briskly. “Let me find a perfect story, and I’ll get back to you.”

What a rush! We congratulated ourselves. We naïvely expected a call in a week or a month. (Now I know “I’ll get back to you” means anything from “tomorrow” to “never.”) It would be almost two years before he returned with absolutely the most perfect story — the story of a Russian mouse family coming to America and the tragedy of getting separated from their little son. During that time, I’d be sorely tested, but I never really gave up hope.

“I’m betting Steven will come through,” I insisted to the man in the mirror. “He’s somewhere out there.”

“Somewhere out there …” mused the reflection. “Great title for a song.”

II. Lessons in Patience

In 1983, amid the hubbub of Dragon’s Lair’s success, Spielberg’s people kept reassuring us that Steven really was searching for the perfect story. Promises don’t help with bills. We saw the road to riches through video games. So we set to work on Dragon’s Lair II and the sci-fi game Space Ace. There was nowhere to go but up, right? Wrong.

Sure enough, the arcade market took a deep dive. The flow of money into the studio slowed to a trickle. Dragon’s Lair II was shelved. And still no word from Steven. I prayed for a second chance.

Most nights I tossed and turned and worried until even my cat, Boots, refused to sleep in my bed anymore. On one of those sleepless nights, my phone rang. I covered my head with a pillow, but the ringing continued. I frowned at my clock and picked up the receiver.

“It’s two in the morning,” I groaned. “How may I help you?”

“Don, this is Michael,” said a breathy voice. “I just saw The Secret of NIMH. It was wonderful.”

I sighed and said, “I’m glad you liked it, but I don’t know anyone by the name of Michael. Have we met?”

“That’s why I’m calling!” he replied. “I want us to work on a project together. Come and see me. We have much to talk about.”

“Help me out,” I pleaded. “Michael who?”

“Michael Jackson.”

“Really,” I said flatly. Superstar Michael Jackson was not someone who phoned common mortals at two in the morning.

He laughed. “Do you want me to sing to you?”

I rolled my eyes. Someone — and I would find out who — was having a lot of fun with this practical joke. “How did you get my number?”

“Oh, that’s easy,” he said, “when you’re me.” He then got down to business. “I’ll have my secretary call you tomorrow with details. We can talk more then.”

After he hung up, I said to the man in the mirror with a yawn, “So I might have had a call from Michael Jackson.”

He shook his head with a chuckle. “As if he would want to work with you.”

The idea that Michael Jackson would want to collaborate seemed so far-fetched that I didn’t tell a soul the next day, not even Gary and John. But lo, a phone call from someone who said she was Michael Jackson’s secretary gave me instructions to follow. The following day, as arranged, I was sitting in the back of a very comfortable stretch limo, heading to a secret location on Santa Monica Boulevard. This sure is quite the elaborate joke, I thought to myself. When the chauffeur pulled the limo into an alleyway and parked next to a nondescript back entrance, I got paranoid: What if I’m walking into a trap set by someone from Disney who wishes me ill? What if I’m being kidnapped and sent off to the Galápagos to be chopped into a thousand pieces and fed to lizards?

The chauffeur’s glare in the rearview mirror caught my attention.

“Er, should I get out?” I asked politely.

“First,” he said, “I have something to tell you. No one gets to see Mr. Jackson. No one. Even I’ve never seen him, and I work for him.” Only then did he open my door and jerk a thumb to the back entrance of the building. And that was when I began to believe.

When I timidly knocked on the back door, it swung open to reveal two very large men in a narrow hallway. They grunted their hellos and led me to a small waiting room, where they patted me down. Satisfied I had no bad intent, they left me alone. I fretted. How does one greet the King of Pop? Should I bow and kiss his hand? The slight man who entered wasn’t like the bigger-than-life superstar I’d seen on videos. Perhaps sensing my nervousness, Michael Jackson hugged me and said, “We’re going to do something together, Don. Something fantastic.”

The man in my mirror had advised me not to be the director and seek control — let the King of Pop take the lead. So when Michael and I sat down together, I listened. He talked about what he wanted to do with his art — make people happy, show them magic. As I wondered why

he was meeting with me, he started talking about movies he wanted to make, like beautiful Christmas stories. I mentioned that Steven Spielberg wanted to collaborate on an animation movie together, and Michael lit up like, well, a Christmas tree.

“Steven and I are doing Peter Pan together,” he confided. “That project is still a big secret though. Don’t tell anyone.” We discussed his ideas, and on impulse I told him about Jonathan Livingston Seagull’s story about the seagull who pushes past doubts to fly ever higher. “Make a budget,” Michael kept saying. “Let’s see what happens.”

By the time I returned to the limo, I was floating on clouds and dazzled by possibilities. I told Gary and John about meeting Michael Jackson and his ideas. I had to convince them I wasn’t hallucinating, and we pinned our hopes on his wanting to do something “fantastic” together.

That night, Michael called me again, and the following night. He liked to talk about ideas — his creative brain never stopped going, especially at two in the morning when he was having trouble sleeping. I began taking naps in the afternoon to keep up with him.

Meanwhile, as far from the fantastic world of Michael Jackson as can be, we were scraping the bottom of our company bank account. We made the decision to pull the plug. Not on Don Bluth Productions but on our beautiful Swiss chalet studio on Ventura Boulevard. We found a more affordable ground-floor industrial space in L.A. and moved operations quickly, but it still felt like starting over.

“Too bad you walked away from Disney,” the man in the mirror said.

“That ended up being a dumb move.”

“It was your idea!” I shouted.

“You do know we’re one and the same, right?” he asked.

I sulked. “Never mind.”

III. The Perfect Story

At last, in 1984, the long-awaited call from Amblin electrified us. Steven had found the perfect story. Gary, John, and I met with him at Amblin, where he arrived fashionably late. He sat down and leaned back in his chair; we leaned forward eagerly, and he began his story. “It’s about a young mouse named Mousie Mousekewitz and his family, who emigrate from Russia to the United States by boat after their home is destroyed by cats. During the trip, a fierce storm throws little Mousie overboard and he loses contact with his family. The story will be his journey to find them again. It’ll be a musical, and we’ll call it An American Tail.” He paused. “Spelled T-A-I-L, not T-A-L-E.”

My first thought was, Another mouse movie? My second was, Hell-a-dee damn. That is a perfect story.

But hold on, you might be saying. Isn’t the mouse in the movie called Fievel? Yup. Steven surprised us one day in Amblin’s conference room when he changed the hero’s name from Mousie to Fievel. The reason is simple: It was the name of Steven’s grandfather from Russia. We kept the surname “Mousekewitz,” but just called the little guy “Fievel.”

A young mouse lost in a strange land, yearning for his family and happiness — anyone would root for the little guy. Something felt off to me though. As Steven kept talking, I realized what it was. Steven was picturing the story in an animal world, and that hadn’t worked for Robin Hood or The Fox and the Hound. I raised my hand timidly, feeling like I was interrupting a master class in filmmaking. “What if … the story took place in the human world? With the little mice dwarfed by human-size ships and houses.”

Steven beamed and nodded his approval. “I’ve seen what you can do,” he assured us. “Go do what you feel is right, then show it to me. I’ll tell you what I think, and we’ll go from there.”

That was how Steven and I worked, especially once he began filming Empire of the Sun in Japan. We sent everything to him for approval, from storyboards to character designs to sequences. He’d mark up the storyboards with excellent points, like “If you do this, it would be funnier.

If you did that, it would be stronger.” Everyone has a gift. His is that he knows how to put cameras in the best place to tell the story. His notes helped me look at each panel that I drew as a way to tell the audience something important — whether it was the characters or the story.

For months, our army of animators steadily inched our way through the sequences. Steven critiqued, we adjusted, he critiqued again, we adjusted again, he approved. Before animating the humans, we shot them in live-action and used their movement to inspire the animators. As for the mice, they had free rein. I mean, who knows how a mouse wearing a shirt and pants and shoes actually walks? We leaned into the pathos of little Fievel’s journey — the terror of the storm, the loss he feels when he realizes he is alone, his anger when he says, “Well, if my family doesn’t care about me, then I don’t care about them.” We made sure to weave in funny jokes, and with Dom DeLuise onboard ad-libbing as Tiger the cat, that was easy.

I was always thinking about how to make this mouse story different from NIMH and The Rescuers. Along with Steven and the marketing department — which was gearing up for cute toys based on the Mousekewitz family — we went for the nostalgic look of Walt’s movies from the 1930s and ’40s, which had a rounded, cuddly feel. To properly show how a storm would toss a big ship, we built a model of the ship that brought the mouse family to America. The “Mouse of Minsk,” which terrorized the cats, was also based on a model.

There were obstacles; that happens on a journey to make a movie. My comedy hero, Sid Caesar, didn’t quite have the right touch I wanted for Henri, the pigeon who welcomes Fievel. Once Christopher Plummer took over the role, we had to rerecord Henri’s lines and even redesign to match the actor’s dignified demeanor. With dailies needing to be approved by Amblin and marketing and Steven in Japan, we began to fall behind schedule. By then, I was feeling so sure of our work that I sometimes made the decision to go ahead and animate without his approval, saying, “If Steven wants us to change it, we’ll just toss it out and start over.” Not the approach I would recommend, of course, but it worked out.

Meanwhile, in 1985, Disney released their much-ballyhooed animated feature The Black Cauldron. They poured millions of dollars into this movie — almost three times An American Tail’s budget, which ended up being $9 million. Our budget was tight, and we had to work fast to make the schedule. It was hard work. There was a lot at stake. Yet every morning the man in the mirror and I were in agreement: We couldn’t believe that a Utah farm boy was working with Steven Spielberg. What a magical experience.

Books you buy through our links may earn us a commission.