Just in case you haven’t had enough of elections, the show now at the Park Avenue Armory, Enemy of the People, hopes you might want to cast a few more votes. Isn’t it fun to pick a future with limited information? Doesn’t all that individual choice make you feel informed and optimistic? At various moments in Enemy of the People, audience members seated at scattered tables are asked to choose between two options by hitting a big X button or a big O button. Brisk discussion is encouraged (a menu-size tabletop screen features a countdown clock), so the whole room buzzes like a restaurant. In the background, Mikaal Sulaiman’s score plays, a convincing dupe of the tension music from shows like Who Wants to Be a Millionaire. High in the vaulted Park Avenue Armory, gigantic billboards show the live tallied results. The first question is about preferring coffee or tea, and I’m glad to report that my table smashed our button as one with the majority. There is an immediate choose-your-own-adventure effect: More people voted for coffee, so the story that night began with a reference to a coffee cup.

Now, Henrik Ibsen’s 1882 An Enemy of the People does not start with coffee — or tea either. It starts with a steak that has gone cold, simultaneously a realistic touch (Ibsen, give or take a few Swedes, invented theatrical realism) and a symbol of mankind’s impatience and gluttony. This 2021 staging — the biggest, fanciest, splashiest in-person indoor theater event in New York since the shutdown — has been radically adapted from that five-act didactic comic drama into a one-woman, 90-minute interactive tragedy by director Robert Icke. (The one woman is Ann Dowd, perhaps most widely known as the creepy Aunt Lydia on The Handmaid’s Tale.) Both Icke’s and Ibsen’s stories start simply. A pompous scientist — turned by Icke from the Norwegian Thomas Stockmann into the modern American Joan Stockman — discovers that the “healing” waters in a spa town are contaminated. Fixing the problem at the baths will wreck the town’s prosperity, so the mayor (also the scientist’s brother) manages to rally the people to his side by demonizing his sibling at a public meeting. That’s basically every current crisis stirred into one — a foul stew of self-interest, economic anxiety, anti-expert sentiment, demagoguery, and infrastructure collapse. It’s hard to pick just one crisis a modern Enemy could be allegorizing. Do you think of Flint? Or COVID? Or global warming? Yes and yes and yes.

There are 11 characters plus “participants in a public meeting” in Ibsen’s play, so even aside from the responsive vote-a-thon stuff, Dowd has a heavy load to bear. Icke’s text is part story theater, part enactment, meaning the actress is sometimes narrating what happened and sometimes showing it to us, as when she (interminably) plays both sides in an escalating argument. The gamified gimmick doesn’t quite make up for all that’s been stripped away, though it does offer the theatergoing set a chilling view of itself. As the show rolls on, the audience makes more consequential choices, but each of our crowdsourced interventions only pushed the show’s characters toward more error and confusion. Welcome back to in-person theater, gang! You suck.

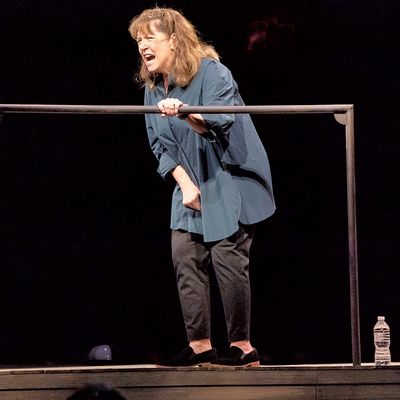

The Armory has the kind of interior that scrambles your sense of measurement. Its cool wooden hugeness always seems like a special effect; how can you walk through a Manhattan door and find this? It is impossible to feel crowded there, and, since the show requires proof of vaccination, most audience members are comfortable enough to take off their masks. By entering (and unmasking?), we become the population of Weston Springs, Icke’s version of Ibsen’s corrupt little burg. The entirety of the massive Drill Hall has been dotted with tables, the vinyl floor printed to look like the town map. Set designer Hildegard Bechtler built a tall wooden catwalk that wanders all through the space, so Dowd prowls over us, about five feet above the ground. She is often quite far away, so we listen through headphones, and cameras broadcast her image to the screens hanging overhead. (Tal Yarden did the video design.) Live and in person, they say, but you’re mostly watching a screen, and it is still processed sound. I took my headphones off from time to time, willing to strain a little just to hear a live human voice.

As Dowd walks around the elevated boardwalk, she sometimes uses screen prompters to help with the lines — the interactive structure must make it difficult to keep track of the text’s branching paths. It’s unfortunate, though, that even with these aide-mémoire she seems so unsteady. Given Joan’s blustering characterization, Dowd needs to grind along like a bulldozer, but the hesitations and shyly lowered eyes (as she checks in with the screens) abrade her performance. It’s hard to know if Icke’s text is really so humorless or if it’s Dowd’s rather grim delivery that makes it seem so. Icke has interpolated a few non-Ibsen characters, who happen to be women (Enemy 1.0 is a bit of a sausagefest), but his attempt at multi-perspectival Rashomon-ism flattens and dies in her voice.

I am willing to admit that Ibsen’s original can be a little … chalky. Old Norwegian Muttonchops never shied away from preachiness, and he was certainly in lecture mode here — Enemy is not as spry and naughty as Hedda Gabler or even, jeez, Rosmersholm. If you dare to wade through Ivo de Figueiredo’s Ibsen biography, you’ll learn he was an unforgiving, cantankerous fellow who started out by espousing revolution but actually loathed the rabble. Ibsen’s play does have an annoying habit of restating its argument act after act. But as much as the original is in need of some rough treatment (my suggestion for the way to do it would be the hilarious 2013 tour of Thomas Ostermeier’s German version), Icke’s rewrite — which includes a character who literally says, “The problem in Weston hadn’t only been with water but with human beings” — manages to keep its tendentiousness while losing its spark and vigor.

There’s a vogue for this sort of thing in British theater: A director takes a famous play in a foreign language, boils the plot’s bones, and refleshes them with a very different story, written in the current vernacular. These aren’t translations or even adaptive modernizations — the relationship to the original is more distant than that. The only truly unchanged thing is that recognizable, marketable title. So far, the main exporter of this stolen-valor technique has been Simon Stone, whose Yerma and Medea have both been to New York. (Yerma was even at the Armory). Now Icke, who has also written plays “after” Aeschylus, Chekhov, and Schiller, shows us his wares as well.

Yet while Icke’s text disappointed me on two fronts (aesthetic and, though it makes me a pearl-clutcher, moral), I was still dazzled by his use of technologically complex mise-en-scène. The Armory’s unwieldy gorgeousness is itself a challenge to creativity, and he rose to it like a salmon jumping upstream. Though the questions audience members vote on can sometimes be ham-fisted (“Who is the Enemy of the People?”), it was illuminating to see how our table actually came to our decisions. We were inconsistent. We asked, “What would Fauci do?” We occasionally tried to torpedo the show from within. (Ibsen would have loved that: His trademark phrase was “Torpedo the ark.”) And over and over again, we demonstrated how democracy produces bad results — through unseriousness and dog-in-the-manger-ism and haste. As a director, Icke did not offer Dowd an environment in which she could comfortably play her role. But he did a bang-up job of tricking us into playing ours.

As in-person theater combat-crawls its way out of its restrictions, the theaterati have been wondering, What will COVID-era drama be about? Will artists deal with the disease? Or will they try to cheer us up? Enemy does try to do both. It’s a flawed script, but Icke and his team have still done impressive work in emotional management. Consulting with my clever tablemates was both rewarding and delightful, possibly the first extended chat with strangers I’ve had since forever. And to be clear: We did a terrible job of making decisions for Weston Springs; we let our community down at every turn. We replicated pretty much every civic and administrative failure of the past year and a half. But screwing up — finally — had zero repercussions. We hit the buttons with increasing giddiness. Choice without responsibility! Voting without outcomes! No fantasy ever felt so good.

Enemy of the People is at the Park Avenue Armory through August 8.