As another wild season of alternate-history interplanetary hijinks draws to a close, it’s time to reflect on what we’ve seen and to look forward to next season. Season three has brought us even more of the big swings that For All Mankind specializes in, and although they don’t all result in great storytelling, I always prefer a bold attempt that doesn’t quite stick the landing to a safer, less interesting set of moves. We won’t get into them all in-depth, but this season finale does a nice job of making some concluding remarks on show-favorite themes including heroism, self-sacrifice, love, loyalty, teamwork, collaboration, individuality, and the drive for exploration that unites these precious (and in one case, quite literal) space babies.

Let’s get some of the biggest questions out of the way right off the bat: Who gets killed off this time? For All Mankind revels in killing its own darlings, so I was convinced that we’d witness another death among the Mars crew, especially now that the three mission groups have merged so successfully. There were so many options! Ed might well crash Popeye; alternately, Ed might kill Danny after his self-serving confession about sabotaging the drill (sorry, but no jury would convict); Kelly and/or her baby might die because of childbirth complications; the newly decorated Official American Hero Will Tyler might nobly sacrifice himself to save his best bud, Rolan. Not that I wish any of them dead, but I do think it’s time for the characters we met and have loved from the beginning to recede into the background. They deserve to enjoy a long and well-deserved retirement the way real people do! They can pop up once or twice each season to provide encouragement and sage wisdom and let the next generation take center stage already.

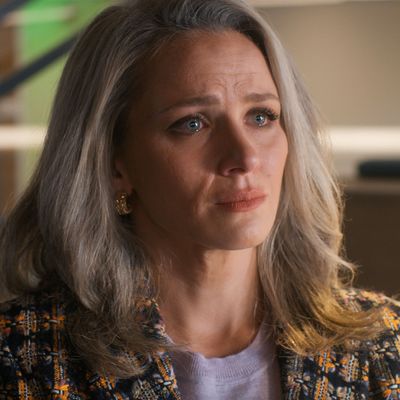

Killing off Karen and Molly both breaks my heart and makes narrative sense. After decades of being thought of as the (ex-)wife of legendary heroic space fellow Ed Baldwin, it’s Karen who saves at least a few lives at JSC, including Jimmy’s, prior to the bomb set off by the domestic terrorists he’s fallen in with. Molly Cobb goes out being the most essential version of herself, the Molly Cobb who couldn’t live with leaving Wubbo out in the solar flare-up on the moon at the beginning of season two. Capably navigating awful situations in service to others is her métier, and she excels to the very end. Card-carrying members of the selfish-pricks club do indeed make the world go round.

For a refreshing change of pace, everyone involved in the long-shot emergency rescue mission of getting Kelly and bébé safely up to Phoenix makes it out alive. Indeed, everything about the Martian Baby Crisis is the exact opposite of how events unfolded at the end of last season. Astronauts and cosmonauts are working harmoniously toward shared goals, nobody is opening fire on or invading others’ bases, and even the space gun that makes an unwelcome appearance at the end of the previous episode is being brandished in suicidal desperation rather than with intent to attack others.

We are even treated to another of For All Mankind’s house specialties, the narratively symmetrical irony of the North Koreans unintentionally coming to the rescue after detritus from their space probe almost destroyed Phoenix back when it was a space hotel. Oh, and did we mention? After all that competition among NASA, Roscosmos, and Helios, what country landed a human on Mars first? North Korea.

Commander Lee Jung-gil is the North Korean astronaut who confronts Dani and Kuznetsov as they approach his capsule to extract the technological doohickey they need to save Kelly. As we learn in a flashback montage that is thrilling, crushingly sad, and even funny by turns, he crash-landed on Mars, which killed his co-pilot and destroyed his communications technology. He’s had MREs aplenty and has been conducting some of his scientific work, but nobody else knows he’s alive, so he’s on a ticking clock, and he knows it. And then he meets Dani and Kuznetsov.

This set piece among the three of them crackles with the energy that leavens even the heaviest scenes in For All Mankind. (Let’s not forget that even as Gordo and Tracy were assembling their duct-tape space suits, they were joking around and being cute together, reminding us that we cared about them as people more than as grim-faced heroes about to sacrifice themselves for the greater good.) Both Dani’s optimistic attempt at totally unintelligible sign language and Kuznetsov’s expeditious tables-turning are perfectly in character, and the scene modulates the flirtatious vibes I noted last week. A fun update for us all: Khrys Marshall, who plays Dani and is the host of the official For All Mankind podcast, tweeted at me over the weekend to say that although early script drafts featured some heart-to-heart conversations between Dani and Kuznetsov, that story line got trimmed out for time. However! Their buddy chemistry is real and was included intentionally.

As we’ve seen, this season of For All Mankind doesn’t take the notion of Gordo and Tracy Stevens’s self-sacrificing act of heroism as gospel. It’s swapped the embrace of the popular narrative around them for uncomfortable (and perhaps unanswerable) follow-up questions rooted in deep skepticism of the entire concept of tragic heroism and its consequences for those left behind. At the end of last season, Danny and Jimmy were orphaned teenagers left holding the flags that had been draped over their parents’ caskets. This season, they’re men-children hovering around 30 without the emotional maturity to show for it. Is it fair to hold them solely accountable for what messes they are? Didn’t NASA and the federal government as a whole owe them something more substantial than those carefully folded flags?

His brother is a whole other story, one that’s a little undercooked. It’s not hard to understand why Jimmy was looking for a sense of belonging or that he thought he’d find it among fellow NASA skeptics. Given For All Mankind’s penchant for structuring major character arcs around alt-historical events that ring a familiar bell for viewers, I understand why there’s a plot line that draws on our timeline’s current mania for conspiracy theories and the very real dangers presented by white nationalists and subscribers to QAnon.

It’s unclear if Charles Manson lite & Co. have always been secret domestic terrorists or if they started out as straightforward propaganda debunkers and then took a turn into amateur freelance bomb-making. Was their plan all along to pull a murderous caper mirroring the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City? The worst attack by domestic terrorists in U.S. history took place in April 1995, right around when this episode takes place, and when we see the damage to JSC, it looks a lot like the damage sustained in the Oklahoma City attack. We only ever see these fake friends from Jimmy’s POV, and he plainly had no idea about the bomb, so we may never know for sure. Of the core group in this subplot, the character who’s had the most screen time is Sunny, and all we really know about her is that she’s a very skilled manipulator of a very sad man.

The other major plotline that doesn’t feel fully realized is Aleida’s investigation of Margo. Having figured out the culprit, Aleida doesn’t seem to know what to do next and agrees to set aside her concerns when Margo pleads for her help with the crisis on Mars. And then the whole thing is over because Margo’s office is destroyed in the bombing, and then we see her in the flash-forward to 2003 in a surprisingly swanky-looking Moscow apartment. Was she extracted just before the bomb went off? Was she kidnapped in retaliation for Sergei’s successful defection? Did she defect? We’ll just have to wait and see when season four picks this narrative thread back up.

I want to wrap up by talking about the fate of Danny Stevens and how it highlights how fully the remaining Mars mission crew members have merged and how well they’ve exchanged competition and secrecy for collaboration and trust. As a result of confessing his responsibility for the landslide, his colleagues vote to banish him in the North Korean capsule. Solitary confinement is an awful punishment, particularly for someone prone to depression and anxiety. But it’s significant that this decision is one the group discussed and voted on, a confident statement that this crew is deeply invested in a model of leadership where authority is not always vested in a particular person. It’s a healthier version of what Dev Ayesa has been preaching (but not really practicing) at Helios all season. It’s wholly of a piece with how they’ve been self-governing for some time. The Happy Valley crew already voted unanimously to use all of their modest fuel supply to save Kelly and her pregnancy; holding a vote to determine the consequences Danny will face is a natural follow-up.

Houston, We Have Some Questions for Next Season:

• Before we get to the questions, I just want to call it now: Ed Baldwin addressing Lee Jung-gil as “my good dumpling” is the single best line of dialogue on American TV this year. I will brook no discussion, this is the apex, no other dialogue need apply.

• Do we think we’ll see more of Ellen and Pam’s story? I’d love to see how they’re doing in 2003, and what the state of LGBTQ+ rights is in a timeline where the leader of a global superpower is an out lesbian.

• Whither Helios? Will Dev Ayesa return as CEO, having internalized lessons from some of the home truths he refused to entertain in the run-up to being ousted by his board in favor of Karen? Can a brilliant, arrogant boy king mature enough to realize his dream of a vast (and perhaps shining) city on Mars?

• How does Aleida move through her grief for Margo? Will she know in 2003 that Margo was extracted from the U.S. by the Soviets, or does everyone think she’s dead?

• Yes, it’s a little on the nose to call Kelly and Alexei’s baby the literal manifestation of their specific collaborative endeavors, but it’s true! Will that wee bairn grow up dreaming of a life exploring the stars? I’m sure we’ll find out next season when the baby will be nearly 10 years old.