For most people, there’s a simple solution when they’re confronted with a video game they don’t enjoy playing: They stop. That’s less of an option for me, being that I make my living writing about games. It becomes even trickier when the maker of the game I dislike — and its entire gameplay philosophy — grow widely admired over the course of a decade, gaining a legion of fans and influencing a whole subgenre of games that follow. This is the story of FromSoftware, a developer that spent 13 years turning its niche brutal action RPG Demon’s Souls into Dark Souls, Bloodborne, and, most recently, the massively popular open-world action-RPG epic Elden Ring. While many players find the difficulty of these games satisfying and character-building, I don’t enjoy any of it, which puts me squarely on the wrong side of video-game history.

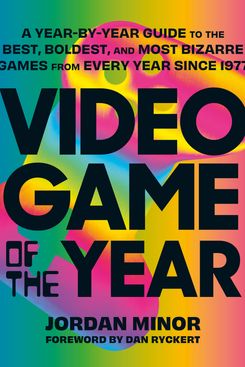

This issue reared its head again while I was writing a book charting the course of said history, Video Game of the Year: A Year-by-Year Guide to the Best, Boldest, and Most Bizarre Games From Every Year Since 1977, which is out today. Each chapter dives into the most important game of a single year, and there was no getting around the need to touch on FromSoftware’s formula. To illustrate how enduring and adaptable the studio’s approach has proven to be, I chose 2019’s Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, a fiendish ninja action game that makes Dark Souls look like a picnic. Sekiro is a brilliantly made game that’s rightfully acclaimed. The problem isn’t the game. It’s me.

While this chapter contains my rebuke of FromSoftware’s punishing brutality in game design, Video Game of the Year also features essays from more than 75 gaming-industry contributors — including several beautifully written articulations of why that very aspect of these games makes them so special. Those writers nearly changed my mind. It’s clear that the verdict on this particular matter falls to the individual player, so perhaps you’ll be inspired to pick up Sekiro’s sword and decide for yourself.

An Excerpt From 'Video Game of the Year'

Soulful

Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice came out in 2019, a full decade after FromSoftware became the developer it is today with Demon’s Souls. That wasn’t the first FromSoftware game; just ask fans of Armored Core and King’s Field. However, FromSoftware blew up with Demon’s Souls and by making later games very much in that game’s style. Demon’s Souls is a gothic fantasy role-playing game obsessed with powerlessness. The story reveals itself to you in cryptic bits, keeping you ignorant and at arm’s length. Class and item descriptions withhold so much crucial information about how everything works that it feels like the game maliciously lies to you. The vague ruined world you walk through suggests a rich history you never got to witness. The best help comes from the literal ghosts of other online players who leave clues as to what to do next, or misinformation meant to send you to your doom.

Demon’s Souls also loves to kill you. A lot. Enemies hit hard. Defensive options come with limits, like shields that break or a stamina bar that depletes with each dodge roll. Lengthy attack animations mean you must commit to your offense with purpose. As an action RPG, technically you can grind to level up, but to do so you need to hold on to harvested souls. When you die, souls you collected get left behind, and if you die again on the way back to retrieve them, all that progress gets wiped out. Death haunts your every waking moment in Demon’s Souls. Whether taking on the numerous titanic bosses or just picking a fight with the wrong skeleton in a dingy hallway, your demise comes for you no matter what.

After an era of easier games for casual audiences, hard-core gamers ate up this harsh but strangely fair mistress. Demon’s Souls demands discipline, patience, and perseverance. If you made a real effort to improve, by studying bosses, practicing techniques, and innately understanding the ill-defined systems, you earned a victory more rewarding than any other. You slayed the dragon. After millions of players conquered Demon’s Souls, director Hidetaka Miyazaki and the team at FromSoftware fed their ravenous new audience more games to prove just how much punishment we could take. Dark Souls popularized the format further, while Bloodborne mixed things up with firearms and a Lovecraftian horror aesthetic. Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice continues this through line. Just saying it’s the next FromSoftware game tells you everything you need to know. However, after ten years of refining immaculately excruciating experiences, Sekiro somehow finds even more paths to pain.

Death Before Dishonor

Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice brought substantial changes to the FromSoftware formula. Instead of trudging through dank European castles, you control a nimble shinobi named Wolf in seventeenth-century Japan. Use your grapple hook to scale Sengoku-era fortresses and pray at Buddhist shrines. Although it takes place in the past, and is fixated on death, Sekiro’s world feels much livelier than the ghostly Souls games. The plot actually bothers explaining itself.

Sekiro’s gameplay shifts to match its new settings with combat centering around your sword, making it less of an RPG and more of a pure action game. You don’t whittle away health, you quickly but carefully land strikes to knock enemies off-balance. It’s a dance where you compete to control the choreography. Break a foe’s posture to deliver a decisive strike to kill in one hit. Supplement your attacks with your prosthetic arm loaded with gadgets like shuriken and flamethrowers. As the subtitle implies, you can immediately revive yourself if you’ve gathered enough energy from fallen opponents. Finally, a FromSoftware game gives you exactly one extra life.

None of these changes make Sekiro any easier than other Souls games. In fact, the opposite is true. At least in an RPG, you can raise your stats to increase your chances. If you can’t learn to execute Sekiro’s lightning-fast, razor-sharp swordplay, you won’t keep up. As a finger-shattering shinobi simulator, it recalls classic action game and fellow cruel master Ninja Gaiden. Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice shows how FromSoftware can introduce all sorts of fresh ideas into its template while maintaining the spirit that drew fans to it in the first place. Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice does right by its legacy. It’s a proud member of a long line of important, innovative, influential games of the year. That’s undeniable. But if we’re being honest, I hate it. I hate these games.

FromSoftware, With Love

I first played Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice as a demo at a press event, and I walked out after an hour. The event was only halfway over, but I felt relieved to reclaim my time and stop playing something that offered me no joy whatsoever. I respect people who like these games. They somehow turned what should’ve been a niche cult hit for masochists into one of the most powerful forces in gaming with millions of sales. But Sekiro solidified for me that during the past ten years FromSoftware has done nothing but make games I can’t stand.

To me, Sekiro isn’t just hard, it’s obnoxious. I enjoy plenty of hard games, but I need them to respect my time. In a game like Cuphead, Hotline Miami, or Super Meat Boy, you’ll bang your head against a wall for hours to finish one particularly nightmarish level. But the levels are so short you’ll either beat them in a few minutes or die and have the chance to try again. You can practice without worrying about losing much progress. In Sekiro, you’ll spend an enormous amount of mental energy to defeat a handful of grunt soldiers, and a few slip ups erase hours of forward momentum. Some see that as ice-cold motivation to try again, a stressful reminder that death has consequences, but I see it as the game giving me the perfect excuse to dip out. I love myself too much to have my time so disrespectfully wasted by a video game of all things. Sekiro isn’t a drill sergeant, it’s not J.K. Simmons in Whiplash. It’s just a hard game I can easily turn off.

What’s worse, though, are the defensive conversations surrounding FromSoftware games and the question of difficulty. Again, people have every right to enjoy punishing games. But difficulty doesn’t always equal quality, and wanting an easier experience doesn’t reflect poorly on your gaming tastes. A game like Celeste handles it perfectly, encouraging players to try the uncompromised original challenge while letting them tweak whatever assist options they want to ease their journey up the mountain. Despite what some game menus might mockingly suggest, there’s no such thing as a baby mode. You might just be a grown-up who can’t devote hours of their life to getting good at one video game.

The snidest purists find the very idea of a Sekiro easy mode so insulting, they think players who mod the game on PC forfeit their gamer honor. FromSoftware designs their games with intent. The cruelty is the point. But so what? Players have been breaking game designers’ intent ever since the late Kazuhisa Hashimoto gifted us thirty extra lives in Contra with the Konami code. Cheating is a vital part of gaming history. Cheat codes make up some of our earliest shared folklore. The only reason they went away is because publishers would rather openly sell you wacky bonuses than lock them behind secret passwords. If you can beat Sekiro blindfolded in under two hours, then more power to you. Be as proud as you want about that accomplishment. But let other people play however they like. Shunning easy modes and cheat codes doesn’t make you a true gamer, it just makes you a fun-policing chump.

FromSoftware games aren’t going anywhere (the PlayStation 5 even launched with a Demon’s Souls remake), and love them or hate them, their unique gameplay cocktail is, at this point, a genre unto itself. And there’s more to it than just difficulty. Games like Hollow Knight and Nioh exhibit a Souls-style offbeat approach to world building and atmosphere.

FromSoftware followed up Sekiro with Elden Ring, a return to Dark Souls–style fantasy made in collaboration with Game of Thrones author George R. R. Martin, and its astounding open-world design made it not only the most acclaimed Souls game but arguably the most approachable. If you can penetrate something this prickly, enjoy the sweet fruits of success waiting within. But don’t feel bad or surprised if you bounced off of Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice as hard as I did. Video games can make you feel a lot of things, but never let shame be one of them.