Gala Porras-Kim watched as a ceiling vent leaked rainwater onto her sculpture, a honey-colored slab laid across a platform the length of a guitar. She was standing in the largest gallery at Amant, a new arts center in industrial East Williamsburg, where her first New York solo show was set to open on November 20. ÔÇ£I heard it!ÔÇØ she exclaimed as a drop pattered on the artwork; she bent down to examine a shallow puddle pooling on its surface. One of the showÔÇÖs curators, Ruth Est├®vez, shuffled over from the other end of the gallery to gaze at the ceiling. ÔÇ£ThatÔÇÖs fantastic,ÔÇØ Est├®vez said.

It was not raining that day, but the galleryÔÇÖs staff had been collecting rainwater for the last week, which they then poured into a basin above the ceiling vent; a valve was calibrated to drip every 20 seconds. Porras-KimÔÇÖs sculpture was molded from a substance called copal, a tree resin used as incense in Mexico and Central America. Mayans on the Yucat├ín Peninsula once offered copal to the rain god Chaac, throwing pieces of it into flooded caves called cenotes; today, in the U.S., this copal can be found amongst pre-Columbian antiquities at museums like the Smithsonian or the Metropolitan, spoils of an era when American archeologists could more or less loot what they wanted. To Porras-Kim, the rainwater drip was a ritual for reuniting the copal with the elements ÔÇö and, maybe, a higher power.

Born in Bogot├í, Colombia, and based in Los Angeles, Porras-Kim makes work about objects, the institutions that house them, and, increasingly, the spiritual lives those objects may lead. ÔÇ£There are artifacts in museum collections that may still be performing their original function,ÔÇØ the 37-year-old explained. ÔÇ£Like, the pillow you go to your afterlife with was technically forever. What happens when an institution takes it and moves it? Can it still function within the museum?ÔÇØ In these scenarios, the artist, who also dabbles in academia, sees herself as mediator between the objectsÔÇÖ original owners (like the rain god Chaac) and the establishments that house them.

Museum collections are invariably built from the spoils of colonization and conquest. Anyone following news about the museum world knows thereÔÇÖs concerted pressure on them to restitute these looted objects ÔÇö and more museums in the U.S. and Europe are starting to heed the call. Porras-Kim said her work aligns with this increasingly vocal push for restitution, but she doesnÔÇÖt take an explicitly activist stance. ÔÇ£Anyone working in the Americas and thinking about history has to think about indigeneity,ÔÇØ she said. ÔÇ£IÔÇÖm dealing with how the ancient past is represented, which of course is all about colonialism, and much of those efforts are about people now.ÔÇØ

She proposes a different kind of return: one that honors an objectÔÇÖs sacred function rather than a nationalistic sense of ownership. She knows this premise could come off as woo-woo, the product of magical thinking that strict rationalists write off. ÔÇ£I think that is part of why IÔÇÖm not a whole academic and IÔÇÖm in the arts,ÔÇØ she said, ÔÇ£because I do know how to do research and all of that, but itÔÇÖs also very dry. If weÔÇÖre trying to understand a broad range of human experience, the ÔÇÿwooÔÇÖ part is important. But too woo is not rigorous enough.ÔÇØ

And Porras-Kim wants to be rigorous, often consulting former grad-school colleagues from UCLA to ensure that her historical ideas are sound. In person, sheÔÇÖs excitable and even silly, elaborating her many-layered concepts in breathless run-on sentences, then cracking jokes about how complicated they are. Her show at Amant, on view until March 17, includes a vast selection of drawings, installations, sculptures, and videos produced between 2019 and now. The scope of the show is at first overwhelming, but the pieces are unified in the way they pose questions about the troubled field of archeology.

It helps that sheÔÇÖs good at convincing museums to let her rummage around in their collections. For the Hammer MuseumÔÇÖs Made in L.A. biennial in 2016, she borrowed artifacts from the UCLA collection that lacked identifying data, then remixed them into replicas that guessed at their original function. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) also gave her keys to its collection, allowing her to reveal its protocol for naming and organizing objects. For her installation at the 2019 Whitney biennial, she produced drawings and sculptures based on an untranslated Mesoamerican tablet held by a Mexican anthropology museum. The most striking of these was a rotating glass disc filled with multicolor characters from the tablet, floating in translucent fluid like a toy from the dentistÔÇÖs office.

ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve always tried to make work that isnÔÇÖt limited to the field of art,ÔÇØ Porras-Kim said. ÔÇ£Like, I have a masterÔÇÖs in Latin American studies and I show at historical conferences. My parents both came from that world, so in a sense, I know how to talk to those people.ÔÇØ

Her father was a literature professor who would bring her on research trips to archives around Colombia; he met Porras-KimÔÇÖs mother, who is South Korean, when she was studying Spanish-language literature at a grad program in Bogot├í. During her childhood, she remembers, many archives in Colombia were housed in the back rooms of colonial churches, and Porras-KimÔÇÖs father used to make up scavenger hunts to keep her busy while he was doing his own digging.

At one such church, he sent Porras-Kim to find the reliquary and retrieve what he said was a saintÔÇÖs pinkie toe. Years later, he admitted that the relic was a chicken toe, planted for her to find. She was shocked. ÔÇ£I really believed it, and then found out it was all a construction,ÔÇØ she said, sitting across from me at a fold-up table in the midst of her half-installed show. ÔÇ£That was the moment where I was like, is anything real? Then I began thinking about what validates an object. Like, just because itÔÇÖs old, is it important? Or just because itÔÇÖs made out of this and not that?ÔÇØ

Porras-Kim says her family fled Colombia for Spain in the mid-ÔÇÖ90s, for reasons she didnÔÇÖt want to make public. After a year in Madrid, they were granted political asylum in the U.S., at the same time as Porras-KimÔÇÖs mother got into a Ph.D. program at UCLA. The family settled permanently in Los Angeles, where Porras-Kim was immersed in the Mexican culture that would later inspire much of her art. She always loved drawing, and her technical skills were sharp by the time she got into the California Institute of the Arts. But at CalArts, her professors seemed more interested in ideas than in pictures, so she learned to balance her formal inclinations with pedagogy, making work inspired by Indigenous languages like Zapotec.

In 2016, Porras-Kim saw a Mexican TV documentary from the ÔÇÖ60s about the excavation of a cenote at the Mayan temple Chich├®n Itz├í, now one of MexicoÔÇÖs busiest tourist destinations. The program focused on the turn-of-the-20th-century American diplomat Edward H. Thompson. After dredging the sacred pool for artifacts, between 1904 and 1911 Thompson took home a breathtaking haul of objects that the Mayans had submerged there: ceramics, gold, jade, obsidian, wood, clothing, and, of course, copal. Sidestepping laws prohibiting the removal of antiquities, he spirited them out of the country and into the vaults of Harvard UniversityÔÇÖs Peabody Museum.

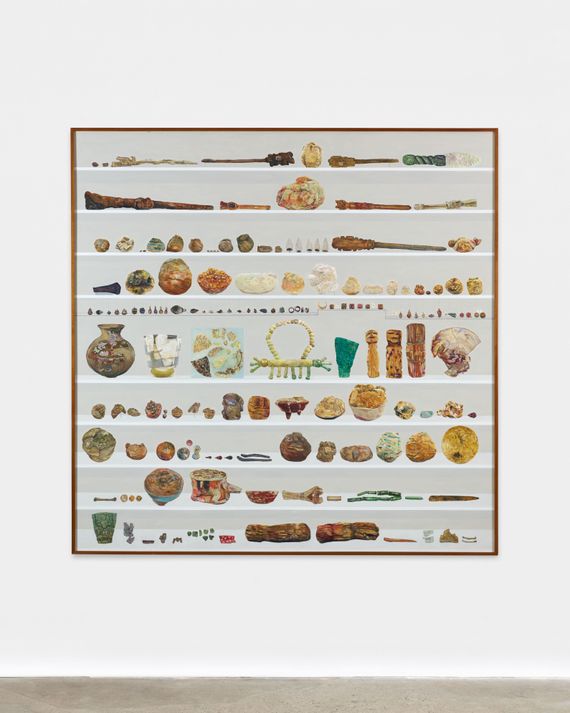

When Harvard opened applications for a 2019 fellowship at Radcliffe, Porras-Kim sent a proposal asking for access to the collection and got in. The result is seven monumental drawings she made there called Offerings for the Rain at the Peabody Museum, now displayed at Amant in the same gallery as her water-soaked copal. In these photorealistic drawings, each six feet square, an array of objects like gold discs, jade necklaces, and ceramic vessels are shown lined up on shelves.

That same year, she also wrote to MexicoÔÇÖs National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) with an offer to create official replicas of a pair of stone monoliths sheÔÇÖd seen at a show at LACMA in 2017. The originals had been extracted from Teotihuacan, MexicoÔÇÖs most-visited pyramids, detected thanks to advancements in lidar scanning, and Porras-Kim wanted to make new monoliths that could be left deep underground in their place. After all, the pyramids at Teotihuacan arenÔÇÖt originals, either: Almost everything but the bases had already been rebuilt as a visual aid for tourists. If archeologists were willing to reconstruct the pyramids to accommodate human visitors, Porras-Kim explained, why wouldnÔÇÖt they consider its nonhuman visitors too? ÔÇ£What if COVID happened because we took the frickinÔÇÖ battery out of that thing?ÔÇØ she asked, laughing. The INAH never wrote back; you can now see Porras-KimÔÇÖs replica monoliths ÔÇö an eight-foot-long tall cigar of painted polyurethane and a five-foot-tall brown one ÔÇö at Amant, where they seem to float, 2001-style, on their rounded tips.

Despite her heady metacommentaries on the fields of art and archeology, Porras-KimÔÇÖs work is almost always beautiful to look at. ÔÇ£My work is mainly the research part,ÔÇØ she explained, ÔÇ£but I also have to think about the audience. I know that if I make some super-research-y, PDF-style piece that doesnÔÇÖt look like anything, then my mom is never going to bring her friends over to see it.ÔÇØ Her works on paper have the kind of exactitude youÔÇÖd expect from a scientific textbook. Her carpal-tunnel-inducing artifact drawings can take three months each to complete, even with a team of four assistants to help with drawing and research. The objectsÔÇÖ sensuous detail ÔÇö the delicate translucence of the jade objects, humming with an electric current of green and yellow ÔÇö clashes with the sterility of the white shelves on which theyÔÇÖre arranged.

People often ask if her work is a form of protest against the hoarding of ethnographic objects, or a way of advocating for change. Porras-Kim insists sheÔÇÖs not proposing solutions. This nonpartisan approach keeps her message from being oversimplified for the sake of an agenda, said curator Ruth Est├®vez: ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs more sincere, more real than just a black-and-white statement, like, this is what should be done.ÔÇØ Instead, Porras-Kim wants us to think harder about what meaningful change might look like. The Peabody Museum could return its ill-gotten gains, to, say, MexicoÔÇÖs INAH. But Mexico as a country didnÔÇÖt exist when the Mayans launched these artifacts into the Chich├®n Itz├í cenote. And even if they were to end up in a vitrine at the Mexico City Museum of Anthropology, they still wouldnÔÇÖt be submerged in rainwater, as their creators intended. Projects like her dripped-on copal are meant to open inquiries into other ways that these artifacts should be treated. She says that, for future showings of the sculpture, sheÔÇÖll require venues to find their own way to reunite it with the rain.

Such gestures might appease the spirits, I added, but what about the humans who want what they think is rightly theirs? She responded by bringing up the Benin Bronzes, a set of thousands of sculptures, reliefs, and other items that were made in the West African city-state known as the Kingdom of Benin, located in what is now Nigeria. They were looted by British soldiers in the late 19th century ÔÇö but recently, museums around the world have begun restoring these objects to the Nigerian government. She seemed to find the way museums were doing this a little too self-promotional, even a little distasteful. She compared the deaccessions to a pancarta, or banner.

ÔÇ£The fact that theyÔÇÖre repatriating big things is really great, but in a way it feels like a Band-Aid solution, like, ÔÇÿThere you go. We did one. The end,ÔÇÖÔÇØ she said. ÔÇ£And IÔÇÖm like, ÔÇÿWhat about the little wood thing in the corner that nobodyÔÇÖs ever gonna pay attention to?ÔÇÖÔÇØ