Looking for some quality comedy entertainment to check out? Who better to turn to for under-the-radar comedy recommendations than comedians? In our recurring series “Underrated,” we chat with writers and performers from the comedy world about an unsung comedy moment of their choosing that they think deserves more praise.

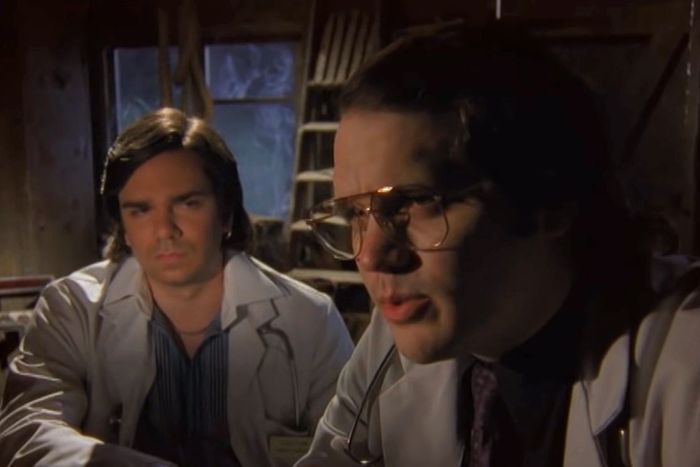

A lot of high-concept comedy comes out of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. When it comes to The Mighty Boosh, Fleabag, and basically any British show that confuses an audience, you can thank Edinburgh. 2004’s Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace is one of the most unique shows of the bunch. Created by Matthew Holness and Richard Ayoade, Darkplace is the fake ’80s supernatural-drama brainchild of horror writer, “dream-weaver, visionary, plus actor” Garth Marenghi. Played by Holness, Marenghi’s show is like if Stephen King’s trailer for Maximum Overdrive got six episodes.

Holness-as-Marenghi opens every episode explaining how the show he and Dean Learner (Ayoade) created in the ’80s was never shown on television until now. You can see why: Darkplace is full of shitty lines delivered terribly amid ugly sets with laughable special effects. Marenghi’s lead character, Dr. Rick Dagless, M.D., is the most glaringly obvious self-insert character since Malcolm & Marie. But that’s all intentional: Holness, Ayoade, Matt Berry, and Alice Lowe are some of the most gifted comedic performers of the aughts, and the show is pitiably awful on purpose. Before you feel sorry for these people for making something this bad, the show cuts in talking-head segments, in which the cast espouses the most pompous, prejudiced, and sometimes legally actionable opinions. It’s MST3K meets The Office. Which is perhaps why Stephen Merchant is such a fan.

Merchant and Ricky Gervais loved the 2000 and 2001 Garth Marenghi stage shows so much that they actually cast Holness as Simon the IT Guy. The admiration was mutual because the Darkplace crew asked Merchant to play an ill-fated cafeteria worker in episode two of its series. But he doesn’t just cook chicken. Merchant now stars opposite Christopher Walken in The Outlaws. Co-created by Merchant and Elgin James, the show follows a group of people sentenced to community service who come together when they’re thrust deeper into Britain’s criminal underbelly. Merchant discussed Darkplace, Berry’s “extraordinary voice,” and visiting Stonehenge with an Academy Award winner.

When did you first encounter Darkplace?

I was at the Edinburgh Festival when it was a theater show. I went to see it several times, and I was so entertained by it. I thought it was so funny. I loved Matthew Holness and Richard Ayoade, the two guys who created it. I don’t think it ever really got the plaudits and attention that it deserved at the time. But I get a tweet or an Instagram message about it almost every day. People are still discovering that show and watching it.

Can you tell me what it was like to first see the show in Edinburgh?

It was unique, really. One of the pleasures of that festival is seeing something fully formed that you’ve never encountered before. Normally when we see stuff on TV, it’s been filtered; some of the edges have been polished off. But [at Edinburgh], you’re seeing something in its raw, purest state. I’m sure the people who saw Fleabag in its formative stages felt the same way.

It seems like the Edinburgh model helps things come out as more singular products. The higher-concept stuff gets through more over there.

So many great comedy performers, particularly in the U.K., have come out of that Edinburgh festival or have found their voice in that environment. It runs for a month. Every possible nook and cranny — every room above a shop — is turned into a theater space, and you don’t need a lot of money. I did an Edinburgh show when I was in university, and I think we had, like, 14 people come through the door in four weeks. But what you’re discovering is how to work with an audience, small as it may be, and how to work with other people. And there’s no pressure. You’re sort of in the dark, left to your own devices. Some people pop and break through — they have their moment, get some attention. And lots of other people use it as a development opportunity, try new things. No idea is outrageous enough or strange enough. And Garth Marenghi is a great example of that.

Vulture has a very strong affinity for Matt Berry. What was it like seeing him for the first time?

Well, Matt is one of those people that, because he has that extraordinary voice, he almost seems like a caricature or a cartoon. His voice is so rich and extraordinary that when you’re talking to him, it’s otherworldly. I think what Matt has is that thing a lot of great comic actors have: He’s handsome, but not quite handsome enough to be a leading man. There’s something about him that almost seems like he was drawn by a cartoonist. Everything I see him in, he creases me up. I don’t know if you’ve seen him as Toast.

Oh yeah.

He’s so innately funny, but he plays it all with an earnestness and a sincerity. It’s so unique. There’s no one else like him, really, as an actor or comic performer. He’s so versatile. He can sing and everything. He’s kind of extraordinary.

If you could cast Matt in anything, what would you want him to be in?

It would be quite fun to see him as a Bond villain. I could see him in a lair, stroking a cat with that extraordinary voice. And I’ve always wanted to play Q, so maybe I could be in it, too. I don’t know who’d play Bond in that version, but that would be fun.

Darkplace is so good it wins over people who aren’t usually fans of cringe-watching or making fun of bad art. How do you feel about “so bad it’s good” content more generally?

Obviously, Marenghi is setting out to seem bad when it’s actually done with great skill. Generally, I’m not a fan of the sort of “so bad it’s good” because there are so many good things I haven’t seen. Why would I waste my time watching bad stuff? Although I remember when I was younger being completely enthralled by Plan 9 From Outer Space, which has become sort of ubiquitous now as “so bad it’s brilliant.” But that was a truly extraordinary piece of bad cinema.

I think anyone who’s tried to get into this business knows how hard it is to make anything — and to do anything good is even harder. So even now, I admire anyone who’s got something finished. I find it hard to be sneery about something because I know how hard it is to get anything done.

But with Darkplace, the little documentary asides puncture any admiration or empathy you could feel for these guys — because they are saying the worst shit imaginable.

That’s the great thing about the Marenghi character: the gap between how they want to be perceived and how they are being perceived. His pomposity and self-aggrandizement is such a great comic convention. And then to see the fruit of his labors, this farcical horror show that’s born from his brain, it’s a great conceit. And all of that was there in the stage show.

How did you get to cameo on the show?

Well, I’d become friends with Richard and Matt, and who do you turn to when you’re looking for people to be in something? I was more than happy to be a part of it. It was kind of hard to get a sense of what the show was going to be because you’re just there for your little bit. But it was a lot of fun. People will still send me little GIFs of me marching through the set. It’s funny because those things, you do them for, like, a day, but they have resonance years later.

Rewatching that episode last night, I was really laughing at your ADR [dubbing] as you rummage for spices in the kitchen.

They wanted the show to really feel like it had been on a shelf since the ’80s, with really bad ADR and things like that. They were very clever in capturing the aesthetic of that period and giving the sense that it was this self-made vanity project of someone from the ’80s. It works on so many levels.

It’s such a contrast to The Outlaws, which is very grounded. Is there one mode of performance you prefer, or are they both fun?

They’re fun in different ways. With Darkplace, the pleasure is that you are living in a heightened universe. Anything goes, really, and you’re almost allowed to do or say anything, and there’s great pleasure in that. That’s much more like playing. When you’re doing something grounded, it’s much harder; you’re trying to keep it just on the right side of reality where you feel like it could still exist in the universe. So you don’t have quite the same freedom to be funny in any direction because you’re trying to keep it in a universe that feels real. But the benefit to that is that you can be more touching, more affecting. You can move people in a different way.

What made you want to do a show about the ways everyday people can find themselves embroiled in crime?

I liked the idea of doing a genre piece, a thriller. I liked the idea of a crime story, but coming at it from a slightly different direction — turning the heat on the characters over time so that by later episodes, you suddenly realize they’re in quite a stew.

But, also, when we were creating the show, we were reacting to the rise of Trump and Brexit in the U.K. There was a real division socially and politically, and we liked the idea of, What if you were forced to find common ground and discover the things which unite us? And that seemed like quite an optimistic flavor to have in a show.

How did Christopher Walken get involved?

Christopher Walken phoned me and said, “I’m desperate for work. Is there anything for me, Steve?”

No, we liked the idea of having a character that sort of felt like a man who fell to earth: Who is this person? Where did he come from? Christopher Walken just sort of came into our heads, and we managed to get the script to him. The next thing I knew, he’d come to England to be in the show. It was sort of insane. Anyone who’s got into this business is thrilled when you find yourself in your hometown with the Academy Award–winning star of The Deer Hunter. It reminds you why you got into this game.

Did people in Bristol react to him, or did they play it cool?

He had the benefit of two things: We shot in lockdown, so he had to wear a mask. And no one was around, so he could walk around and not get noticed.

Although he and I did go to Stonehenge together. We had a day off, and Chris really wanted to go to Stonehenge. We got there, and he went to the woman showing us around: “Can I touch one of the stones?” And she was like, “No.” I took her to one side and said, “He’s 78 years old. He’s an Academy Award winner. He’s Christopher Walken. He’s come 3,000 miles. These things have been here 5,000 years. You can’t just let him touch a stone?” And she’s like, “No. Definitely not.” It was so typically British that even someone like Christopher Walken can’t touch the stones. “Definitely not.” That’s not how we roll in England.

Do you know why he wanted to see Stonehenge of all things?

I guess when you’re Christopher Walken, you’ve done everything. There’s not much left on your bucket list. I think he’s something of a history buff. It was really magical. He found it quite moving to watch the sunset with something as mysterious and exotic as that. It was a surreal moment.

This is all I’m going to think about for the rest of the day: you and Christopher Walken at Stonehenge.

That’s right.

Do you have any pet theories as to what it is? Clock or altar or yada yada yada?

The general consensus seems to be that it’s probably to do with a burial or some kind of ceremonial environment, which makes sense to me. But certainly when you’re there … I’m not someone who’s kind of spiritual, but it puts you in touch with the past in some way. The idea that people 5,000 years ago decided to start putting up rocks — I don’t know why that makes you feel very connected to the past. Well, I suppose it’s obvious why. But there’s something quite pleasing about that. And to share it with Christopher Walken is doubly pleasing.

More From This Series

- F Is for Family: Bill Burr’s Love Letter to the ’70s

- It’s Time to Appreciate SNL’s ‘Riley’ Sketch, Bitch

- Take a Bite Out of Horowitz & Spector