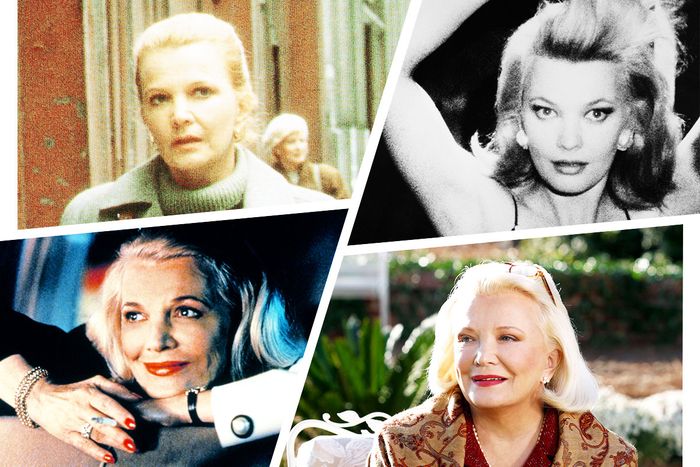

This article was originally published on July 31, 2024. We’re republishing it with the news of Gena Rowlands’ death.

In a 1982 interview, Tennessee Williams said that we must bear witness, spread the word, and show respect to those who endow us with their souls. “I’ll give you a list,” he said of the rare few who had the courage to do such a thing, “and the first name is that of Gena Rowlands.”

Most will recognize Rowlands as one of the leads in 2004’s The Notebook, in which she played an older woman living with dementia. Cinephiles will know her best as an icon of the ’70s New Hollywood era, when she worked with her husband, John Cassavetes, to launch the independent-film movement in America and create some of the most emotionally acrobatic and bare films in western cinema. In Opening Night, Faces, and A Woman Under the Influence, to name a few, Rowlands pioneered a new style of oversize, twitchy, realism-meets-vaudevillian acting and showed us a range of feeling that only she seemed able to access.

In each of her roles, before she retired from her decadeslong career in 2015, Rowlands’s natural defenses were lowered to reveal the things the rest of us go to great lengths to conceal: the terror, irresolution, and indeterminacy at the heart of life. Rowlands was disinterested in neat conclusions, tidy fictions, anything that wasn’t entirely honest. For her, acting was an opportunity to explore the gendered politics of heterosexual romance and how difficult — and usually impossible — it is to live among others who exist in their own neuroses and philosophies and on their own terms.

She was a rigorous student of film — and especially adored the scrappy glamour of Bette Davis — something that’s easy to forget when you watch her in action. Across her filmography, Rowlands performed with a fluidity that seemed closer to real-life behavior than to movie acting. It’s for that reason that her performances have often been mistaken for improvisation despite the methodicalness she brought to them. A reader first, she based many of her performances on her own script analysis, bringing total command and authorship to her roles.

In her later career, after the death of her husband, she picked up a series of bit parts in several soapy films (and appeared in the odd episode of NCIS), yet her performances were just as soul-shaking in these undeserving roles as they were in her work with Cassavetes. Even that role in The Notebook.

In June, Nick Cassavetes, Rowlands’s son and the director of The Notebook, revealed to Entertainment Weekly that, like her character in the film, Rowlands had been living with dementia: “We lived it, she acted it, and now it’s on us.”

If there has ever been a time to bear witness, spread the word, and show respect to Rowlands, it’s now. Every hair-raising gesture, every movement all her own, every nerve and muscle in her body that went into every single one of her performances — her soul is there. These are ten of Rowlands’s most essential roles and no doubt some of the finest, most transformative acting you’re ever likely to bear witness to.

Lonely Are the Brave (1962)

Rowlands appears in only a couple scenes of David Miller’s Lonely Are the Brave — a film that follows a standpat cowboy (Kirk Douglas) and his attempt to flee a rapidly modernizing America — but her very brief presence as Douglas’s best friend’s wife is enough to see a genre in transition, turning the western existential. It is deeply disconcerting to see emotions as real as Rowlands’s in a genre that had by then become so trope-y. Performing alongside a rascally Douglas and a resolute Michael Kane (who plays her husband), Rowlands’s stifled feelings practically quiver on her face. She carries the burden of an abandoned woman, filled both with a rage toward the man who leaves her at home and a reluctant tenderness toward men who can’t help but depart. “Believe you me, if it didn’t take men to make babies, I wouldn’t have anything to do with any of you,” she snaps at Kane in a particularly intense scene.

Rowlands’s character, lovelorn and aimless, is what’s left over when wild romance inevitably fails. The parting scene between her and Douglas is no doubt the film’s best. As she kisses her cowboy good-bye, her composure crumbles and gives way to an almost unbearable tenderness. Mia Farrow, whom Rowlands would later star alongside in Woody Allen’s Another Woman, told Elle how much the performance had affected her as a teenager: “I’d never seen anyone that beautiful with a certain gravitas.”

Faces (1968)

The first of Rowlands and Cassavetes’s major collaborations together, Faces is a disheveled piece of indie cinema that introduced the themes that would define the rest of the couple’s work together: love, marriage, alcohol, and the politics between men and women. While only a flitting presence here, Rowlands’s tertiary character, a sex worker named Jeannie Rapp, is by far the most memorable part of the film. Cassavetes’s twitchy handheld camera searches restlessly around each scene before settling on Rowlands’s face. Through the 16-mm. grain, you find something daring and devastating in Rowlands’s eyes. See how long you can stare at them when she says she’s “too old to be lovely,” a single tear hanging from her lashes, before feeling you should look away. Rowlands’s performance in Faces is like a challenge to look at someone’s soul without flinching. It’s proof that she can dominate a film with her face alone — and what a face it is.

Minnie and Moskowitz (1971)

No one in the history of cinema has made sunglasses look as good as Rowlands does in Cassavetes’s dysfunctional screwball comedy Minnie and Moskowitz. While practically every man she encounters in the film — including her shithead boyfriend, Moskowitz (Seymour Cassel) —berates her, manhandles her, and physically assaults her to varying degrees, Rowlands carries herself with rhapsodic grace, staring coolly beneath her octagonal Linda Farrows — until she can no longer maintain that composure.

Here, Rowlands plays a Los Angeles County Museum of Art curator who watches romance films and gets wine-drunk at night, then has her cinematic delusions of love shattered by day. “Movies are a conspiracy,” she says motionlessly. It’s with the arrival of Moskowitz that the film then takes a turn toward the erratic.

Together, Rowlands and Cassel deliver one of the most sickeningly overstimulating performances you’re ever likely to see. Minnie and Moskowitz is a drunken ballet of uncontained emotions meted out between two lovers who turn each other into their wildest selves. Moskowitz destroys any sense of Minnie’s restraint, ultimately giving Rowlands free rein to do what she does best: unravel in the most spectacular and disturbing ways.

A Woman Under the Influence (1974)

In her best role, Rowlands plays Mabel Longhetti in A Woman Under the Influence, Cassavetes’s magnum opus and possibly one of the greatest depictions of heterosexual dysfunction ever committed to screen. Every crack in Rowlands’s voice, every earsplitting inflection, every bizarre gesture is a masterstroke of acting genius. Her performance is both wildly operatic and troublingly lifelike, so much so that you can’t help but worry for Rowlands. It’s difficult to believe that her performance isn’t improvised, but no — it’s scripted, studied, and she really is in control of such an unruly character.

Starring — and sparring — alongside Peter Falk, Rowlands’s character is a lower-middle-class mother of three experiencing each day as an unceasing series of crises. She is without a center or a stable sense of self, trying her best to communicate the profound love she feels for her family but rarely reaching them in a language they can understand. She is in a permanent state of tantrum and acts out with a kind of capricious whimsicality, shouting, dancing, grimacing like a child forced to eat vegetables, much to the embarrassment of her blue-collar husband.

After Mabel is admitted to a psychiatric hospital, the film’s tone turns from droll to a straight-up horror show. The disputes between Rowlands and Falk are so unsettlingly real they feel as though they’re happening in your own home. Watching it is like witnessing a terrible miracle.

Opening Night (1977)

Rowlands and Cassavetes’s seventh film together calls into question the borders between fiction and reality as well as the humiliating treatment of female actresses. In Opening Night, Rowlands plays Myrtle Gordon, a seasoned actress struggling to connect with her latest Broadway role: a middle-aged woman unable to accept her lost youth. At every turn, Myrtle resists her director and co-stars’ — including Cassavetes, who plays her husband, Maurice — perceptions and expectations of her, instead choosing to forge her own drunken, wild, maniacal path. She goes off-kilter completely when she’s told that her character will be slapped onstage. She walks off and appears at the play’s titular opening-night blind drunk. Here, we see Rowlands at her most vaudevillian, each of her movements highly unpredictable and ticlike. She meets intense theatricality with stinging naturalism, doing what only Rowlands could: turning farce into something incredibly disturbing and severe.

Gloria (1980)

Cassavetes’s most conventional and least characteristic film also sees Rowlands stepping out of her typically intimate style. Playing the titular character, a middle-aged, childless moll, she saves a 6-year-old boy (John Adames) from the clutches of the mobsters who killed his family, spending the rest of the film fleeing them.

Gloria was a screenplay Cassavetes sold to Universal to help fund his more experimental films. While he initially declined to direct, Rowlands demanded that he reconsider once she’d been cast as the film’s lead. Cassavetes eventually relented, knowing it would be a favor to his wife — the woman who’d grown up idolizing Bette Davis’s foolhardiness and self-sufficiency — who had long yearned for a role that would tap into her scrappy, tough-guy side.

As Gloria, Rowlands displays a greater sense of exteriority than we’re used to seeing from her, particularly in her inward-driven Cassavetes roles. Clearly written for a big studio, there’s less of a focus on probing monologues or much opportunity for deep character exploration at all. The film is all gun-toting, door-busting, gallivanting action. Any sense of interiority appears only in easily missable flashes. Gloria is really a chance to see Rowlands’s physicality displayed at large: the way she hunches over the mob bosses like a goblin, the way she strides, the way she holds a gun better than even Dirty Harry could.

Love Streams (1984)

Hardly seen at the time of its quiet release, Love Streams became a lost relic before the Criterion Collection rescued it from obscurity in 2014, releasing it on to Blu-ray for the first time. Love Streams was possibly Cassavetes’s greatest treatise on his philosophy of love and altogether one of Rowlands’s most complex performances. Bouncing off each other in emotional chaos, here the couple play brother and sister in what would ultimately be their final film together. Sick with cirrhosis of the liver, Cassavetes was told he’d have six months to live shortly before he began work on the film (a diagnosis he did not reveal to anyone else at the time; he went on to live another five years).

Here, Rowlands plays Sarah Lawson, a self-effacing love addict with no sense of self beyond her relation to others. Cassavetes plays Robert Harmon, a writer living in his own individualistic world who confronts his sister with her own lack of self. “What is creativity, Robert? Is cooking an art? Is love an art?” Sarah asks him, her hand gestures as delicate as Tai Chi’s. As in several other of her roles under Cassavetes, Rowlands’s character goes to farcical lengths to prove her own personhood. She takes herself on a solo bowling date, brings home a menagerie of farm animals, visits a joke shop, and tries desperately — and unsuccessfully — to make her ex-husband and daughter laugh with a clown nose, chattering teeth, and googly eyes. Like all Cassavetes films, Love Streams asks what two people who are desperate for love to the point of insanity can truly give each other. What happens when lines become tangled and communication breaks down entirely? And as is also typical of Cassavetes, Love Streams presents love and alcohol as two sides of the same coin: a destabilizing force that utterly undoes anyone under its influence (not unlike Rowlands herself).

Another Woman (1988)

Woody Allen’s underdiscussed Another Woman stars Rowlands as Marion Post, a cold-tempered philosophy professor who suffers a sexual-based crisis just before she turns 50. “I don’t know who I am anymore,” she says with an eerie sense of detachment when she overhears the other woman’s (Mia Farrow) therapy session.

Another Woman is Allen at his most turgid and Bergmanesque — which might explain its lack of viewership. This is a decidedly different role for Rowlands; not only is she mousy-haired and dowdy, a far cry from her usual blonde-bombshell looks, but she is also given a much smaller range of emotion to play with. Unlike the wild and loose characters she played under Cassavetes, as Marion she is finicky and fastidious. With less surfaced emotion, Rowlands acts on a minute scale, each detail too tiny to be enlarged into words. Yet with every small furrow of her brow, Rowlands is somehow able to convey at least seven emotions at once. It’s microscopic and brilliant.

Night on Earth (1991)

Jim Jarmusch’s Night on Earth, a series of vignettes from five different cities around the world, was Rowlands’s first feature after her husband’s death in 1989. In the film’s Los Angeles section, she stars as a power-playing talent agent who takes a cab ride from a plucky tomboy (Winona Ryder, who is admittedly a little hacky here). The two share a cigarette during the drive to the talent agent’s hotel, Ryder’s character dirt-faced and scuzzy, Rowlands’s clean, sharp, and sangfroid. Together, they reveal the two sides of Los Angeles, its underbelly and its glamour, as they’re forced to coexist together for a 20-minute cab ride. While Ryder is far less convincing in her part, Rowlands is sublime as ever, conveying a very subtle sense of discontent beneath her errorless manners. A lesser actress might have come across as matronly in this role, but Rowlands is just too fabulous.

The Notebook (2004)

Rowlands’s performance in The Notebook as a woman living with Alzheimer’s now carries a sharp sense of tragedy. Nick Cassavetes, her son and the director of the film, recently announced to Entertainment Weekly that she has been living with the disease for the past five years. Rowlands’s mother had suffered with it, too, an experience that made it almost impossible for Rowlands to accept the role of Allie Hamilton in The Notebook. “If Nick hadn’t directed the film, I don’t think I would have gone for it — it’s just too hard,” she told O, the Oprah Magazine in 2004. But whether it was her husband or son, Rowlands always delivered her best performances while under the instruction of the people she loved. Her son was by then more familiar with his mother’s acting than just about anyone else had been, having spent his childhood tripping over camera wires in the family home, where John Cassavetes shot most of his later films. Although The Notebook, an adaptation of Nicholas Sparks’s mawkish beach read, isn’t exactly the groundbreaking cinema commonly associated with the late Cassavetes, Rowlands plays Allie with the same courage she brought to any of her husband’s productions. She even adds an element of horror to an otherwise play-it-by-numbers romance, her moans of impatience and pain so ugly and animal that it’s difficult to get them out of your head. What was once just uncomfortable to watch is now heartbreaking.