If music biopics often feel redundant, that’s because the lives of many famous musicians have taken similarly reckless turns. Success on the charts often goes hand in hand with drinking or drug problems, adultery, disagreements with managers, arguments with collaborators, and strained marriages. We’ve seen it all before in Oscar-nominated movies and pretty much every episode of Behind the Music.

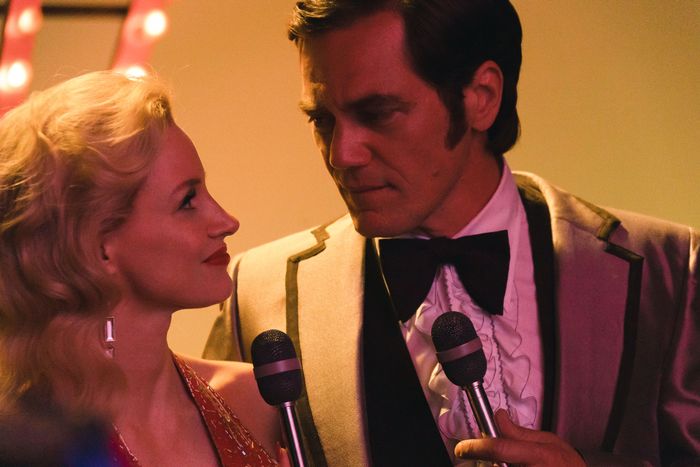

We see most of those things again in George & Tammy, the six-episode Showtime series premiering Sunday, December 4, about the passionate marriage and musical collaboration between country stars George Jones and Tammy Wynette. Jones, played by a towering Michael Shannon, is a notorious drinker who flings himself into terrifying rages every time he drains a bottle. Wynette, infused with warmth and dignity by Jessica Chastain, eventually becomes addicted to the painkillers she relies on to ease the crippling aches from a botched hysterectomy. Over the years, they flirt, argue, make love, and create beautiful music together, music sung for real in this series by Shannon and Chastain. When the two actors harmonize, they may not sound exactly like Jones and Wynette, but their voices reach out for and ease into each other like bodies spooning in a queen-size bed.

It’s those factors — the lead performances and George & Tammy’s reverence for the couple’s country discography — that make this limited series something richer than a typical biopic. It doesn’t even feel quite right to call this a biopic, since it doesn’t trace the entire lives of its primary subjects so much as the life of their relationship, which begins in the 1960s when record executive Billy Sherrill (David Wilson Barnes) introduces Wynette to Jones and persuades the more established artist to let Wynette, a huge fan, open for him.

Even those unfamiliar with the general trajectory of their lives will know immediately that Wynette won’t stay married much longer to her second husband, aspiring songwriter Don Chapel (Pat Healy), once she locks eyes with Jones. In an early scene that’s echoed later in the series, their desire for each other practically jumps off the screen as Tammy, a former beautician, washes George’s hair and gives him a trim. “You’re flirting with me, George Jones,” Tammy scolds, clearly basking in the admiring gaze Jones is throwing toward her. “You’re pointing your finger at me, Tammy Wynette,” he responds, playfully, not looking away for even a millisecond.

It’s vital that there be chemistry between these two, and Chastain and Shannon have so much crackling between them it’s practically visible. But to the credit of series creator Abe Sylvia, who wrote The Eyes of Tammy Faye, the film that won Chastain an Oscar, the show does not romanticize their feelings or bond. This is less a love story than a depiction of need: George and Tammy need each other, they need their music, and, inevitably, they need their mind-altering substances. That trio of needs is what motivates both of them and makes them so in tune with one another. Even though director John Hillcoat (The Road, Corazón), who helms all six episodes, gives their love scenes a glowing intimacy, there is subtext beneath every one of them hinting at the darker side of their codependency.

It’s especially exciting to watch Chastain and Shannan perform onstage together, each playing to the crowd while looking into each other’s eyes as if no one else is there. George & Tammy smartly lets its musical moments run free, sometimes for whole songs, in ways that enhance the overall narrative. Watching Tammy make it all the way through her signature hit, “Stand by Your Man” when George fails to show up as expected to a Vegas concert is a tiny roller coaster ride. A later sequence when George opens for Tammy and plays a deliberately long set out of spite serves as both a comedic set piece and an illustration of how petty George can be toward the love of his life.

Shannon in particular hits some amusing grace notes within his thoroughly constructed dramatic portrayal of the country legend. When George is at one of his many low points, his friend and guitarist, Peanutt Montgomery (the great Walton Goggins), asks if he can pray over him. In response, Shannon mumbles, “If it’ll make you feel better, Little Jesus.” Seconds later, Shannon is sobbing, explaining that Jesus “could have had me by now but he doesn’t want me.” Those are big emotional swings that could induce whiplash in another actor’s hands. But Shannon makes you believe that this deeply troubled man can turn on a dime, homing in on his vulnerability in softer scenes and using his imposing six-foot-plus frame to its most menacing advantage when George explodes.

Chastain meets him more than halfway, exuding maternal energy that extends to Tammy’s own numerous children, George, who may as well be one of her kids, and anyone with whom she comes in contact. She can come across as fragile, especially in her relationship with George Richey (Steve Zahn), the family friend who eventually becomes her third husband and chief enabler of her drug habit. But she also puts her stubborn, b.s.-averse side on full display, a reminder that, despite the lyrics to “Stand by Your Man,” this woman is no pushover. Chastain’s ability to summon tears to her eyes without letting them fall is practically an act of wizardry.

While the series does not glamorize Tammy’s weaknesses, it does deify her a bit. Most of the people in her inner circle tend not to get mad at her, even when they have very good reason. Even Richey’s wife, Sheila (Kelly McCormack), a close friend of Tammy’s, immediately forgives the singer for pursuing a romantic relationship with her own husband. There are also strong implications that Richey initially had sex with Tammy only after drugging her, but the series, based on a book by Wynette and Jones’s daughter Georgette, is vaguer than it could have been about the nature and extent of Richey’s abuse. That marriage is really skimmed over instead of dissected.

Perhaps that’s inevitable. A show called George & Tammy should care most about George and Tammy and this one does, very much. Even if the broader outlines of its story are reminiscent of other music-focused films and shows, what makes this portrait so watchable is the shading brought to it by Chastain and Shannon. They show up in every episode with every color of paint on their palette, and display an effortless sense of control over every single stroke.