Henry Kingi is the recipient of Vulture’s second Stunt Award: Lifetime Achievement. Read about the winners of the 2024 celebration of stunt professionals here.

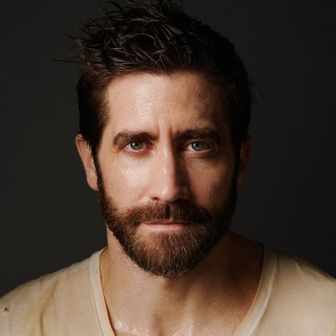

Henry Kingi’s long dark hair spills over his shoulders as he staggers backwards on a roof, guns shaking in both hands, blood streaked across his sweaty face. He’s running from something the audience can’t see — something that has his character, a leather-vest-wearing cartel leader named El Scorpio, in its heat-vision sights. When an LAPD officer explodes onto the roof and takes aim at El Scorpio, he thinks he has no choice. He screams, raises his arms in two rigid lines just above the cop, and starts spraying bullets. Unaware that El Scorpio isn’t shooting at him, the cop unloads his own gunfire, and whatever was hunting El Scorpio watches as the impact pushes his body over the edge of the building — his legs kicking, his gun still firing, as he spins to fall face first to his death.

At 80 years old, Kingi has over 80 acting credits on IMDb. He was on The Bionic Woman, T.J. Hooker, The A-Team (he did all the major jumps in the van) and Walker, Texas Ranger; he appears in Scarface, the original Road House, Batman Returns, Blade, and (fast forward many years to a very different superhero era) Ant-Man and the Wasp. He has over twice as many stunt credits, most recently in the John Wick and Fast & Furious universes. Name a franchise with flashy driving sequences (Kingi specialized in vehicular stunts) — Dune, Lethal Weapon, Star Trek, Speed, Jurassic Park, The Matrix, Bad Boys, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre — and he’s done stunt work for it.

The Action Edition

Yet his role as the gun-toting, free-falling El Scorpio in Predator 2 remains his most recognizable. Kingi’s wavy locks and arching eyebrows get center stage for more screen time in the Stephen Hopkins sequel than was typical for the performer who considered himself a stuntman first — a “stuntman’s stuntman” as director Craig Baxley describes him. To this day, Kingi prides himself more on blending in on-screen than standing out — because of his mixed ancestry (he is of Native American, African American, Japanese and European descent ), the Hollywood lifer says he is like a “chameleon,” capable of doubling for almost any person behind the wheel, including Mr. T. Of course, this description downplays the amount of time Kingi spent attracting attention off camera, heaving doors open for the many labor organizers who are refashioning his industry today.

“One thing about Henry, he has always been a humble and unassuming man,” Baxley says. “A stuntman who was always under the radar, not like most of the blowhard stuntmen in the industry. People would see most of the stunts he did and ask, ‘Who did that?’ To this day, they still don’t know he did them.”

Kingi says he never thought film, let alone stunt work, was a possibility for his future. Even though his mom was friends with Dorothy Dandridge, who when she visited would tell Kingi and his perfect head of hair, “I’m going to get you in the movies.” He did a little modeling in the all-Black publication Elegant Magazine here, worked in venues like Maverick’s Flat there, until a chance meeting with prolific photographer and vocalist for the music group the Hi-Fis, Lamonte McLemore, who had come by the club with stuntman Eddie Smith looking for Black extras for a scene in the 1967 Dr. Dolittle. After making $400 in only two days of work, he said, “This is what I need to do! Where has this been?”

Once he was accepted into the Extras Guild, Kingi became involved with the 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers, a group of Black stunt performers who would participate in battle recreations during Black History Month. Thanks to the cavalry, he learned how to fight and ride horses, his naturally lithe body suited to the work. His love for driving was more accidental. On the set of Dukes of Hazard, Baxley and his father Paul asked Kingi to take part in a driving scene and he demonstrated a preternatural ability to drift. “Everybody was like, ‘Shit! How did you do that?’” Kingi recalls. “I said, ‘I don’t know!’”

At the time, Hollywood was embracing a practice known as “painting down.” Instead of hiring Black stuntmen to provide the double work for Black actors in action scenes, the production would paint white stunt performers — “not beige, not brown, flat out Black,” recalls Kingi. He says fellow stuntman Eddie Smith, was working on the set of It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963) when he approached director Stanley Kramer and asked him why he wasn’t using a Black stuntman to drive for supporting cast member Eddie “Rochester” Anderson. “Bring me one,” Kramer responded.

Smith and Kingi would do more than bring him one stuntman. To ensure that directors would know of and have no reason not to hire Black stunt performers, Smith (as president) and Kingi (as vice president) co-founded the Black Stuntman’s Association along with several of their peers. It was small at first (15 people, including co-founder Calvin Brown, who was hired to double for Bill Cosby after he refused to use painted-down stunt doubles on the set of I Spy) and, according to Kingi, met with immediate resistance by white production members. In the old days, Kingi says he had to take his headshot directly to a stunt coordinator to get a job; after forming the BSA, those coordinators wouldn’t take any meetings with Black performers. When the BSA started showing up at sets to demonstrate in front of productions that were painting down, animosity only grew.

Between protests, BSA members would bring mattresses out to Athens Park in Los Angeles, and practice maneuvers. (Kingi says these sessions were often watched by individuals in unmarked copy cars; he and his co-founders believe their meetings were being mistaken for Black Panther gatherings.) These trainings helped Kingi jump feet first into Hollywood action, first showing up uncredited in Alfred Hitchcock’s Topaz in 1969. He moved through Blaxploitation classics like Cleopatra Jones, and sci-fi like Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972) and the Charleton Heston disaster picture Earthquake (1974). Kingi is all over ‘70s and ‘80s television from there, most notably The Bionic Woman, where he met his second wife, Lindsay Wagner. He even worked with last year’s winner of this very award, Albert Pyun, on the latter’s debut, The Sword and the Sorcerer. He’d team again with Baxley on a few of his more beloved features too, Action Jackson and Stone Cold.

By the ‘90s and early 2000s, Kingi was so well established as an action player he was regularly working with mega-directors like John McTiernan and Michael Bay. On Bay’s Bad Boys II, Kingi says he performed the hardest stunt of his career (and arguably Bay’s most audacious to that point). Coming towards the end of the film, as Will Smith and Martin Lawrence descend on a Cuban village in a yellow Hummer, they crash and tumble down a mountainside full of shack houses. Calling to mind the opening of Police Story, they tear through house after house, obliterating everything in their path. Kingi says that when he was scouting the location, he realized the abandoned shacks had iron beds, stoves, and refrigerators inside of them, which forced the production to gut the buildings before barreling cars full speed through them.

One potential catastrophe averted; still, Kingi says the actual Hummer shoot was the only time he ever prayed while performing a stunt. As he drove down the mountain, the Hummer would lift off the ground, and each time it came back down, it would land in an exploding pile of wood. When he finally halted at the bottom of the run, he noticed a graze on his hand. And then he saw it: a piece of wood had somehow made it inside, despite the car’s bulletproof half-inch Lexan glass, and came within inches of piercing his chest. “I was worried about the cliff,” he said, not “a piece of pine — cheap, little softwood.” With stuntwork comes endless planning and meticulous attention to detail, along with a willingness to take what comes.

The stakes of Kingi’s vehicular stuntwork only skyrocketed when he joined The Fast and the Furious crew. Brought aboard on the fourth entry, Fast and Furious, by Spiros Razatos, a stunt coordinator for the franchise he first worked with on Sidney J. Furie’s The Rage in ‘93, Kingi would end up working in some capacity on each installment from then on. Kingi was integral to a spectacular vault heist sequence in 2011’s Fast Five (which made into 2023’s Fast X as well, in flashback), during which Dom and his crew lift a vault from a police station by hook it to two Dodge Chargers and driving away, with Dwayne Johnson’s team of agents on a wild chase behind them.

Director Justin Lin and the stunt team chose to go practical with the shoot, fearing too much weightlessness if the pinballing vault were to be rendered completely digitally. So instead, they put Kingi in a pickup truck, tore off the hood, built a vault around it, and had the stuntman drive the creation in tandem with the two Chargers. (If you’re wondering if Kingi was roasting inside the glorified box, he was. Fellow stunt performer Jack Gill had to build a cool vest out of some dry ice, and fashion a hose for fresh air directly into Kingi’s helmet, to manage the heat.)

It’s stories like these that underscore the absurdity of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’s refusal to honor stunt performers and coordinators with its own Oscars category. Kingi credits Gill with working the hardest to change this and cites Tom Cruise’s advocacy as a major boon to the cause. Earlier this year, the Academy announced it would be introducing an award for achievement in casting, signaling the Oscars might be open to acknowledging more below-the-line work like Kingi’s.

But it isn’t just awards ceremonies that are leaving stunt performers out. An entire summer and fall of strikes came and went in Hollywood, and little was made of the impact streaming and residuals has on stunt performers, who have historically been denied a seat at the negotiating table. (Ignored by everyone except, according to Kingi, Cruise. As the Screen Actors Guild negotiated with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers last year, Kingi recalls Cruise telling both sides, “You should probably listen to what the stunt people have to say.”) But just as he did over a century ago with the BSA, Kingi maintains a vested interest in a more equitable industry — it is, after all, a family business for him, with all three of his sons working in stunts today.

More From The Action Edition

- Picking His Fights

- The Thoroughly Goofy, Undeniably Seductive, All-in-One Charm of Shah Rukh Khan

- Watch Out for the Killer Gams