The fact that filmmaker Boots Riley’s new TV series I’m a Virgo is a Prime Video project may seem incongruous. In his music with hip-hop group the Coup, his feature-film debut Sorry to Bother You, and his years of activism and organizing, Riley has been vehement in his criticisms of capitalism and corporations. More than 20 years ago, the Coup released a song called “5 Million Ways to Kill a C.E.O.”; now, the first season of I’m a Virgo is on the streaming service made possible by Jeff Bezos’s success. But Riley has said that he went with Prime Video to get his series, and its ideology, in front of as many viewers as possible, and I’m a Virgo is as unequivocal in its distrust of the ruling class, the police, and the one percent as it is fantastical and surreal, a cacophonous collage of animation, music, and practical effects that creates a world in which anything is possible — even a revolution.

“Someone might say, ‘We already know this. Why is this in here?’” Riley says of detractors to I’m a Virgo’s characters identifying as communists and their message that America is in dire need of a united working class. “If you already know it, it’s because you’ve had conversations in your life. If all of these filmmakers have had these conversations in their lives, how come there’s never been a character talking about it?”

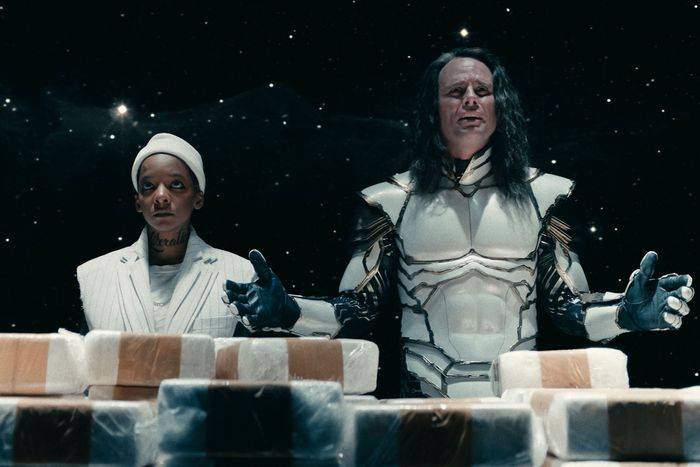

Unlike anything else on TV in both its absurdist visual identity and its penetrating political fervor, I’m a Virgo follows a 13-foot-tall 19-year-old Black man named Cootie (Jharrel Jerome) as he’s raised by his uncle Martisse (Mike Epps) and aunt LaFrancine (Carmen Ejogo) and idolizes The Hero, a vigilante identity assumed by tech billionaire and comic-book publisher Jay Whittle (Walton Goggins). After Cootie ventures out into the world, he makes his first friends, including organizer Jones (Kara Young); starts his first relationship with the similarly superpowered Flora (Olivia Washington); and realizes that The Hero is not the moral figure he thought he was. The series’ alternate-reality Oakland, built by Riley and co-showrunner Tze Chun, is bold, bleak, and beautiful, with the growing solidarity of its characters a sign of Riley’s own resilient hopefulness. As Cootie comes of age in the middle of a growing political movement, I’m a Virgo questions what steps are most effective in getting people to want to change their material conditions, so Riley spoke to Vulture about the series’ answers — and which of them may arrive in a potential second season.

Cootie is raised by an adoptive family; he’s prepared for an important mission; he has a rash that spreads all over his body and seemingly reveals a different physiology. Given how I’m a Virgo involves superheroes and myths, is Cootie your version of Superman?

No, it wasn’t my version of Superman. I start with the contradiction: What ripples does being a giant Black man cause in the world that we know? The first document I wrote talking about this show was entitled “Super Villain.” So definitely wasn’t Superman, right? In the show, he kind of becomes the villain. There are people cheering him on and people who are not, and that’s what happens in real life. We watch shows about bank robberies and we love them because we know who’s the bad guy in that, and it’s not the characters robbing the banks. The only time the characters robbing the banks are bad guys are when it’s a cop show or superhero show, and that tells us something about the influence these shows have on us.

I built Cootie from the inside. It’s always who the person is. As far as the physiology, it points to something else. There will probably be a second season, and that’ll be answered there. It was actually going to be answered in the last scene of this season, but weirdly, we cut 60 percent of the show during prep, and that was one of the scenes that had to go. And if there isn’t a second season, I’ll publicly answer it for folks.

The series felt to me like a mishmash of different myths: the polypheme; the comic books; the myths America tells about itself, like the role of the police and the morality of the criminal justice system. How did those other elements come in?

I usually try to take things from the inside out. I go from a problem, and it grows, and I’m trying to make people feel things along the way. Those things find their way in because they’re in the world. The Hero is called The Hero because of the idea of how you’re supposed to tell a story, the hero’s journey, and then Jones is a storyteller and tells stories in different ways.

All those things come from solving a problem, trying to figure out how to get this idea across. How do I make this experience that our character’s having not just information — that we know he went through this — how do I make it so that we feel that? At the beginning, he’s in this house that’s too small for him, and we could get that feeling from him crouching over, but a visual registering of that comes when they’re painting part of the house yellow, so we feel it in a different way. I’m looking for these visceral things to make us feel these experiences and feel these ideas. And maybe I don’t even know exactly what I mean by “feel,” but a brain registering it as something that’s a little uncomfortable or strange.

Also, there are a lot of clues that give us an idea of what Martisse and LaFrancine are going through. To put it in your words, they are a part of almost another mythology that now would be happening in that second season. All of those things will become clear.

Was cutting in service of having things for a potential second season?

No, it was strictly money. We cut it in prep weeks before we were gonna go shoot. Leaning on practical effects made the whole thing take a lot longer, which is part of why there were other things that we had to cut — and some of why I think the show works. There were things that broke my heart to lose, but it ends up being greatest hits. When we would perform on tour, we’re used to doing an hour and 20 minutes, but then we’d get the opening slot on some other show, and they’re like, “You got 20 minutes!” And we’d be like, “Now we just cut out all the fat, and we’re just gonna slap people in the face with the hits.”

There was more story line for Lower Bottom Folks, there were some other characters, this and that. There was a friendship rivalry between Bear and another character that doesn’t exist that had to do with the whole neighborhood of Lower Bottom getting one job. That rival was going to be a Vietnamese character. The Bay Area is very diverse: Black people, Asian folks, a lot of Persian people, a lot of Arab people. But because we ended up filming a lot of this in New Orleans, that’s not what you’re gonna get for background actors. You’re gonna get Black folks or white folks. I feel like there’s something missing from some of the representation of the Bay Area. That character that Bear works with, maybe we can bring him back.

When did Flora and Jones, who also have abilities, come into play?

With Jones, I knew one of the friend group was going to be an organizer. In that psychic theater in episode seven, that argument was going to originally be made by Cootie, and it was going to happen during a long battle, just a verbal thing. Then I thought, Wait. So I’m gonna have an episode with a conversation? I gotta make this more of an experiential thing. I also started thinking, Will I change Cootie a little bit from my initial idea of him? That’s something he just wouldn’t be talking about. That’s something Jones would say. But she wouldn’t say it if it was going to be boring. She has the power of being really good at arguing. What does that power look like? It had to feel different than the rest of the language of the show. It would have to be stagecraft stuff that would actually feel like something new and different. I wanted us to feel like her powers were to make people understand a thing. She’s not like Professor X. Her girlfriend is able to say no, and Jones had to wait for The Hero to be willing to listen. She can’t change somebody’s feelings or thoughts.

When I first wrote the character that became Flora, it was an absurdist view of people having to work too hard. Who is this person? How is she able to do that, and what does that really mean for her? Her power is that everything is slower and she’s bored. How do I represent that? I wanted it to feel uncomfortable and odd, like a David Lynch thing. I wanted to do it in a way that didn’t just say, This is fast, but felt wrong. We filmed that with Olivia doing the action once and then we’d have different women in different spandex suits do the action. I chose to make the powers be things people didn’t recognize in themselves as powers until Cootie came along. I’m trying to ramp up the contradictions in people’s lives and what they’re doing and how they experience things, in a similar way that Cassius had the power to do this white voice in Sorry to Bother You.

I’m a Virgo centers a tension between Cootie’s attack on the power station, which is one bold act, and the organized, collaborative general strike, which is supported by Jones. We don’t really get a lot of media that goes into a discussion of the benefits or flaws of each approach, which is what LaFrancine and Jones do when they talk about revolutionary leaders. How did you decide that this tension would be so central?

These are conversations that happen in real life, right? These are ideas that are being talked about and ideas I’m thinking about in general, and that my work tries to talk about. What is power? Where is the point of power? Where is our power? There’s a whole genre of heist movies, people robbing banks and stuff, and everybody loves them. In those situations, nobody thinks the bank is the good guy. People cheer for that to happen. To have that conflict, I wanted there to be a quote-unquote heist. We had a whole episode we storyboarded that would have been amazing, but was part of that 60 percent that got cut.

What are people cheering for when they’re cheering for those heist movies? They’re feeling like someone is expressing their power, and giving those in power — the ruling class — what they deserve by taking from them. And that sometimes gets spilled out into our regular life when we look at the world. We see a basketball player got $200 million and they came from poverty, and we’re cheering because we feel like that is doing something to the system — in some way, shape, or form, we got part of that money. Somehow, it’s right! But we also know at the same time that it doesn’t actually change anything about the system. That is in conflict with the things, the mass movements, that might be just as forceful, just as violent, but take a lot of people to do it, and that actually can bring about change. So I want to posit those individual adventurous acts versus the mass movements to build power and take things over. One of them doesn’t get talked about in cultural production at all and one does, because it’s the placeholder for these feelings we have of wanting the world to be different and wanting the world to change. And so I made the heist the power plant to give it some semblance of, this is something they’re not doing just to get money for themselves or whatever. It’s to help people, but it still symbolizes that same contradiction.

I wondered if the series was rejecting the idea that radical acts of violence can be inspirational.

That’s one of the conflicts that’s in the show: this sort of vanguard idea, which is what you see LaFrancine putting forward. It’s something that definitely existed in certain parts of the left in the United States, but when you look at the revolutions that did happen, it wasn’t from these individual acts of violence. They were violent, but they were millions of people. China, millions of people; some of them didn’t even have guns, but it was violent because they had so many people, and they could battle groups that did have guns. You look at the Soviet Union, Cuba. We look at Cuba, and people are like, “There was Che, there was Fidel,” but they were having general strikes at the time, and that was part of why they were able to take power.

I’m fascinated by Parking Tickets, the animated show within the show. In the clips we see, characters talk about death being an equalizer; they embody the lost opportunity of an unfulfilled life. What did you want to convey through Parking Tickets?

The idea for the show came from something I used to say to my kids. I’d be like, “You’re spending all this time watching TV because you think what they’re doing on TV is exciting. Notice that their life seems exciting because they’re not sitting around watching TV.” So much of our life is spent like that. What they’re taking in is part of them and part of the character of the world. I thought, I need to see something that people are seeing. I created this idea where all the writers of Parking Tickets really want to be doing something more important than what they’re doing, and also are a little bit stuck on themselves. They’re arrogant and think they’re the best writers. I started with that first scene of Parking Tickets in episode two. I wanted them to be saying real things, but in a way that those writers felt was taking that kind of television up a notch. Whether it is in real life or not, I don’t know. But I wanted them to feel like they were answering and positing existential questions, and as they were pitching this show, they couldn’t get it sold, so they had to have this stupid catchphrase. I also wanted to use the show as a way for us to feel how Cootie feels left out, because everybody’s laughing at the show and he doesn’t understand what’s funny about it.

Justin, who says “Boyoyoyoyoyoyoing,” that’s Juliette Lewis. I know her brother Beau Patrick Coulon because he directed the Coup’s video for “The Guillotine.” She was like, “I’ll do it, but they’re telling me I’m on six episodes. I don’t have the time for that.” I was like, “Don’t worry, you’ll be able to do everything in ten minutes.” And she was like, “Okay, but where’s the script?” And I’m like, “It’s the one word.”

And let’s give credit where credit is due: The weatherman episode and the existential despair, that’s Tze. I wanted Parking Tickets in there, but when you’re dealing with everybody wanting to cut things for money, you look for ways to save things. I’m like, “What if this was one of the tools that they needed to use for the heist?” And then Tze was like, “I got an idea.” I guess there’s a Pokémon episode that in Japan got banned because they had all these blinking lights — that’s Tze’s ideas right there. And my friends, Ri Crawford and David Lauer, who live in Oakland and did the stop-motion animation on Sorry to Bother You, were doing this two-and-a-half-D thing with planes of characters here, then planes back here, and doing it stop-motion, but looking sort of flat. It’s a little unsettling in the sense that it’s like some other things you’ve seen before, but weirder. Making a Parking Tickets show has definitely been talked about.

For people who watched I’m a Virgo and Sorry to Bother You, which are about labor movements, and are reading about the WGA strike, what films or books would you recommend as the labor-movement canon?

Labor-movement-canon films — there aren’t a lot of them. A lot of movies from the ’70s that get talked about as being pro-labor, like Paul Schrader’s Blue Collar, it’s definitely anti-union. There was a backlash to what was happening at the time: There was this strike wave in the early ’70s, and so you saw a lot of media that had labor in there, but portrayed it as corrupt. But one that is very inspiring is Matewan by John Sayles. There’s a book called Class Struggle Unionism by Joe Burns that just came out. A History of America in Ten Strikes by Erik Loomis; A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn is a good place for folks to start if they’re not familiar with any of that stuff, because it puts things in perspective. There’s a movie called Seeing Red, it’s a 1983 film by Jim Klein and Julia Reichert. There’s a documentary on YouTube, Rocking the Foundations, about the New South Wales Builders Labourers Federation from 1940 to 1975. This one Builders Labourers union had some corrupt leadership, they got those leaders kicked out, and they became a militant union. In the ’60s, they became so militant they were able to get all of their demands. They wouldn’t just stop scabs at the strike line, they’d go to the scabs’ houses and make sure they didn’t come to work. They got so powerful that when there were other campaigns happening in the community — there was gentrification going on; there was their Black power movement, which were of Indigenous people there — they were able to aid those struggles by shutting down the building developments and the businesses that those movements were fighting against.

We spoke when Sorry to Bother You came out, and you told me you believe movies and pop culture help create the status quo rather than reflecting it. They have a phenomenal influence on what we normalize and accept. When Whittle started saying that in his speech at Cannon Comics, I was reminded of our conversation, but I was surprised to hear that “all art is propaganda” observation coming from Whittle, who is the series’ villain and, I assumed, someone whose perspective we should distrust. I’m curious how you decided to have him voice that.

I think there’s this idea — and I don’t think it’s entirely wrong — that capitalism just operates on automatic. People kind of get into modes. They get a job, they might be doing something they would philosophically otherwise disagree with, and it’s just that you have this job, it’s a function. But at the same time, there are certain parts of the capitalist class that do think ideologically. You can see it in certain people like Elon Musk, where they think about how they want the world to be, and they try to put out ideas, like, “Hey, things should be this way.”

“I have a certain amount of money, therefore, I get more say in how things should go.”

Yeah, and they also care what people think about that, because it helps their business. For instance, this anonymous Apple executive that did this interview, one of the reasons that they’re against the writers strike getting what they want is they’re worried about how that story will be perceived by other workers in other industries, and what that story will make those other workers do. There is definitely self-awareness and class consciousness in the ruling class, meaning they know how things work and they use them to their benefit.

Jay Whittle thinks things should be a certain way. The reason why I’m having him say that is because we are seeing more and more evidence that the capitalist class understands how capitalism works and understands how media works and understands how these stories should and shouldn’t be told. We have in Hollywood a really strong connection between the Pentagon, the CIA, and Hollywood. It’s not even hidden. Why do they care? We know that the CIA takes orders from the ruling class, too. “Hey, we’ve got these markets in this country that are threatened by this particular movement. We need you to do something about it.” Whose interests are those folks working for? I think that there are people in those positions thinking about more than the immediate need for profit. They’re thinking about the power that they have and how they can shape the world, and it’s not necessarily from an analysis that is unclear about the way things are. That’s why I have him saying these things.

Jay Whittle is acknowledging that there is a shared truth, but there is a specific spin that is being placed on it by the ruling class.

Yeah. And along the terms of what Jay Whittle was talking about, I’ll show you right quick: There’s a book by Lenin called What Is to Be Done?, a seminal statement that was made early on in the Revolution, and really held them together at an important time and allowed them to make gains. He called it What Is to be Done? because of this book [holds up to camera], What Is to Be Done?, which is a work of fiction from the late 1860s by Nikolay Chernyshevsky. When I found out about this book a few months ago, I found out that the revolutionaries of the early 1900s were all inspired by this fiction book about a utopian society. I’ve always asked myself the question, What am I doing with my art? Does it really have an effect in that way? This has been a major eye-opener for me. I can always talk about the model of how these works of art we watch shape our view of the world, but there’s always a question, when you’re making radical art, of whether it can have any effect or not, and that’s an example of that.

More From This Series

- The Best TV Shows of 2023

- What Jharrel Jerome Learned While Staring Down a 13-Foot Version of Himself

- Boots the Myth-matician